Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

A 2,000-year-old fortress built on a mountainside in what’s now Iraqi Kurdistan could be part of a lost royal city called Natounia.

With the help of drone photography, archaeologists excavated and cataloged thesite during a series of digs between 2009 and 2022. Situated in the Zagros Mountains, the stone fortress of Rabana-Merquly comprises fortifications nearly 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) long, two smaller settlements, carved rock reliefs and a religious complex.

The fortress was on the border of Adiabene, a minor kingdom governed by the kings of a local dynasty. These rulers would have paid tribute to the neighboring Parthian Empire, which extended over parts of Iran and Mesopotamia approximately 2,000 years ago, according to research led byMichael Brown, a researcher at the Institute of Prehistory, Protohistory and Near-Eastern Archaeology of Heidelberg University in Germany, with the help of Iraqi colleagues.

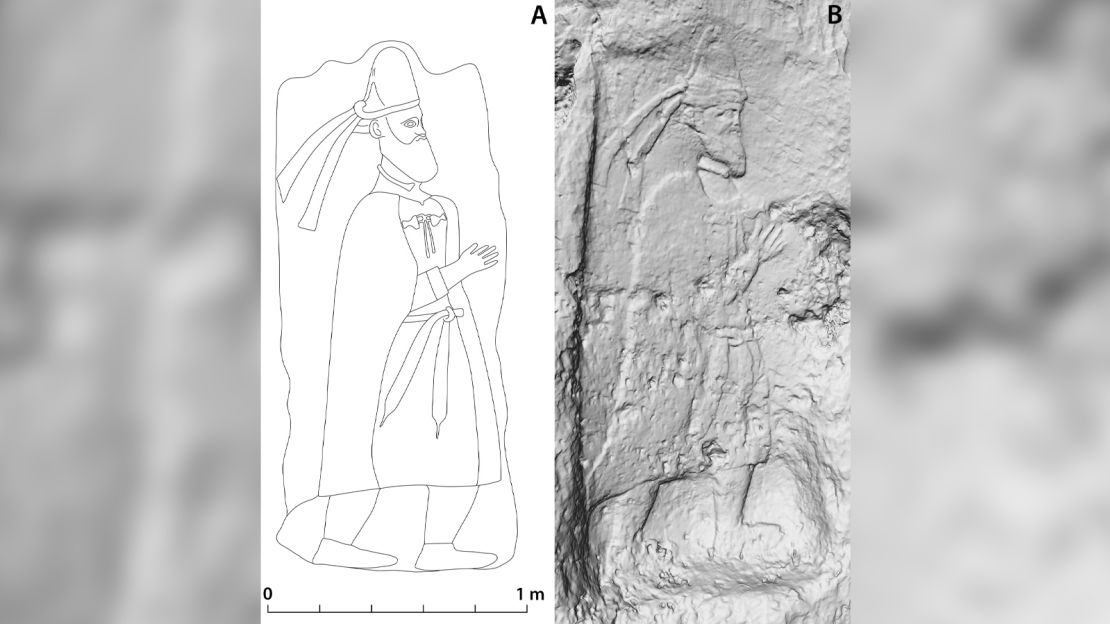

Carvings at the entrance to the fortress depict a king of Adiabene, based on the dress of the figure, in particular his hat, Brown said. The carving resembles other likenesses of Adiabene kings, particularly one found 143 miles (230 kilometers) away at the site of an ancient city called Hatra.

While it’s matter of speculation, Brown believes the fort was the royal city known as Natounia, or alternatively Natounissarokerta, that was part of the kingdom of Adiabene.

“Natounia is only really known from its rare coins, there are (not)any detailed historical references,” Brown said via email.

Details deduced from seven coins describe a city named after a king called Natounissar and a location on the Lower Zab River, known in ancient times as the Kapros River.

“The location near to (but admittedly not on) the Lower Zab/ancient Kapros river, short occupation, and royal imagery all link the archaeological site to the description we can deduce from coinage. There are also some unusual high status tombs nearby,” Brown said.

“It’s a circumstantial argument. … Rabana-Merquly is not the only possibility for Natounia, but arguably the best candidate by far (for) the ‘lost’ city, which has to be in the region somewhere.”

The king in the carving could be the founder of Natounia, either Natounissar or a direct descendant.

The place name Natounissarokerta is composed of the royal name Natounissar, the founder of the Adiabene royal dynasty, and the Parthian word for moat or fortification, the study also said.

“This description could apply to Rabana-Merquly,” Brown said. As a major settlement positioned at the intersection between highland and lowland zones, it’s likely that Rabana-Merquly may have been used, among other things, to trade with pastoral tribes, maintain diplomatic ties, or exert military pressure.

“The considerable effort that must have gone into planning, building and maintaining a fortress of this size points to governmental activities,” Brown said.

The study said the discovery adds to our knowledge of Parthian archaeology and history, which remains markedly incomplete, despite its evident significance as a major power in the ancient Near East.

The journal Antiquity published the research on Tuesday.