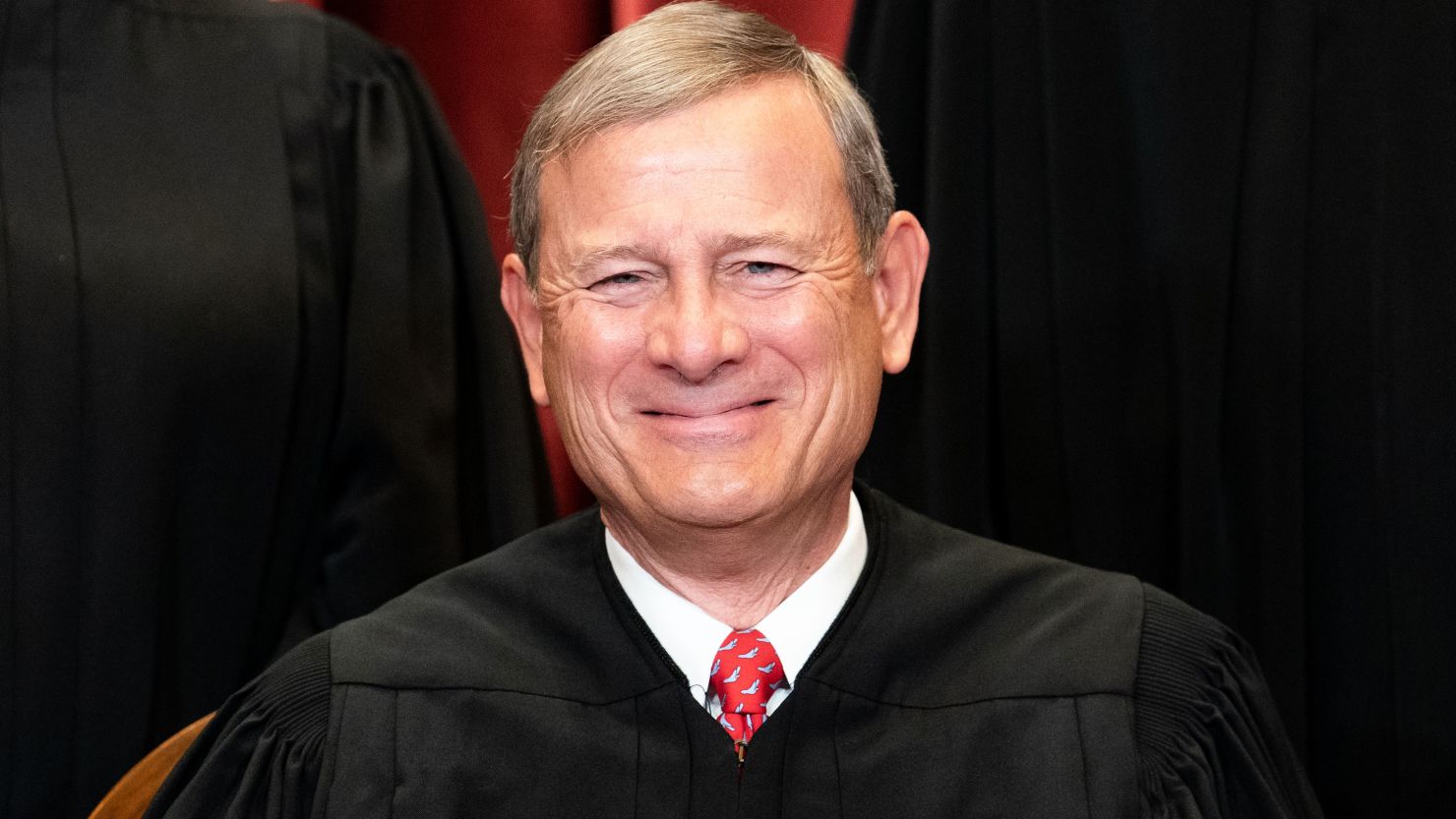

Chief Justice John Roberts has been laying the groundwork for years for Tuesday’s sweeping decision requiring states to fund religious education.

But he always tried to signal some caution. Five years ago, in a financing dispute involving a church school in Missouri, he even added a footnote that said the Supreme Court decision applied only to money for playground resurfacing. Fellow conservatives called him out and suggested the caveat was preposterous because the decision would, of course, reach other religious funding cases.

And it did, by Roberts’ own hand – in 2020 and then on Tuesday, when the strategic chief justice took a giant stride and wrote the decision holding that Maine must pay for religious education as part of a tuition-assistance program for private schools. The rationale once cast as limited to playgrounds has been extended to a swath of religious instruction.

Tuesday’s opinion reinforces Roberts’ conservative bona fides, even as he regularly tries to find middle ground to enhance the court’s institutionalism and image.

The Supreme Court is in the final days of its annual session, negotiating on abortion rights, gun control and environmental protection, among other controversies. Roberts is likely to try to keep the new conservative supermajority from pushing too far to the right in some areas, including abortion rights, where he has pressed for a compromise decision that would not completely overturn Roe v. Wade.

But as Tuesday’s decision in Carson v. Makin underscores, he remains truly at home on the right wing. He has been part of a majority that consistently rules for religious conservatives, not only with public funding for church schools but also for prayer at public meetings and additional exemptions to the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive coverage mandate.

In his opinion on Tuesday for the six justices on the right, Roberts insisted the ruling simply flowed from the principles applied in the 2017 and 2020 cases.

But unlike those limited rulings in cases from Missouri and then Montana, the Maine decision specifically involves funds that would be used for religious education, and it demonstrates as forcefully as ever that state rules that might have been regarded as neutral in the past can be invalidated as religiously discriminatory.

The earlier decisions authored by Roberts forbade states from excluding religious schools for public funding based solely on their religious “status” or “character.” The new case tested whether a state that subsidizes private education could withhold funds based on a school’s religious “use.” And in requiring public money to be used for instruction that promotes religion, the court generated a raft of new questions about the separation of church and state.

“What happens when ‘may’ becomes ‘must’?” Justice Stephen Breyer, the court’s senior liberal, wrote in a dissent. “Does that transformation mean that a school district that pays for public schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to send their children to religious schools? Does it mean that school districts that give vouchers for use at charter schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to give their children a religious education?”

The Maine case arose at the intersection of the First Amendment’s two religion clauses, prohibiting government’s “establishment of religion” and guaranteeing its “free exercise.”

The disputed program provided money for students to attend private schools in areas that lacked public high schools but excluded sectarian institutions, defined in part as those “associated with a particular faith or belief system and which, in addition to teaching academic subjects, promotes the faith or belief system with which it is associated.”

The Supreme Court struck down that exclusion based on the First Amendment’s protection for the free exercise of religion. Roberts said Maine’s exclusion was based on a stricter separation of church and state than the Constitution requires.

Breyer, however, asserted that the majority “pays almost no attention to the words of the first Clause while giving almost exclusive attention to the words in the second.” He noted that the two clauses are often in tension and states have sufficient leeway to further “antiestablishment interests” by withholding money for religious schools without impinging on free exercise.

He was joined in his dissent by fellow liberals Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, and Sotomayor also wrote separately to recall that she had sent up a flare five years ago, in the case of Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer, when Roberts set down his principles on the intersection of the First Amendment establishment and free exercise clauses.

“I warned in Trinity Lutheran … that the Court’s analysis could be manipulated,” Sotomayor wrote, then added, “This Court should not have started down this path five years ago.”

Back in 2017, Roberts had declared that Missouri had unconstitutionally excluded the Trinity Lutheran Church’s Child Learning Center, based on its religious “status,” from a program that offered grants to non-profit groups for the purchase of playground surfaces made from recycled tires.

Roberts’ narrow rationale, as well as a footnote asserting that the case “involves express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing,” helped draw Kagan, and, to a lesser extent, Breyer, onto the decision. (Sotomayor had dissented with the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was succeeded in October 2020 by Justice Amy Coney Barrett.)

Roberts reinforced the status-vs.-use distinction in the 2020 case of Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, when he wrote that states may not bar schools from participating in student-aid programs solely because of the schools’ religious character.

On Tuesday, the chief justice demonstrated he had never been locked into the distinction.

“In Trinity Lutheran and Espinoza, we held that the Free Exercise Clause forbids discrimination on the basis of religious status,” he wrote. “But those decisions never suggested that use-based discrimination is any less offensive to the Free Exercise Clause.”

Rebuffing dissenters’ assertion of the importance of “government neutrality,” Roberts declared that “there is nothing neutral about Maine’s program. The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools – so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion.”

He added: “A State’s antiestablishment interest does not justify enactments that exclude some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.”

Dissenters countered that nothing in the free exercise clause would “compel” Maine to give tuition aid to private schools that will use the funds to provide a religious education, and they used Roberts’ prior cases to support their position.

“(T)his Court’s decisions in Trinity Lutheran and Espinoza prohibit States from denying aid to religious schools solely because of a school’s religious status—that is, its affiliation with or control by a religious organization,” Breyer said. “But we have never said that the Free Exercise Clause prohibits States from withholding funds because of the religious use to which the money will be put.”

Back in 2017, Roberts had taken pains to observe that he was not addressing “religious uses of funding.”

At the time, Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, said Roberts’ division between religious status and religious use made no sense.

“Respectfully, I harbor doubts about the stability of such a line,” Gorsuch wrote in a concurring opinion. “Does a religious man say grace before dinner? Or does a man begin his meal in a religious manner? Is it a religious group that built the playground? Or did a group build the playground so it might be used to advance a religious mission?”

“I worry,” Gorsuch added, “that some might mistakenly read it to suggest that only ‘playground resurfacing’ cases, or only those with some association with children’s safety or health, or perhaps some other social good we find sufficiently worthy, are governed by” the ruling.

Gorsuch need not have been concerned. Roberts was getting there, although moving incrementally. Tuesday, Gorsuch and the other conservatives joined Roberts’ decision with no caveats. None of the liberals, of course, appeared tempted to join this time.