The mayor of Uvalde, Texas, visibly frustrated with the constantly changing information released about what happened the day 19 children and two teachers were gunned down, lashed out Tuesday, telling residents at a city council meeting he’s tired of being kept in the dark about what evidence has been uncovered.

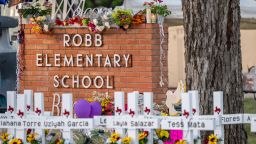

At the meeting, Mayor Don McLaughlin also said Robb Elementary, where the massacre occurred May 24, will be razed.

“You could never ask a child to go back or a teacher to go back to that school. Ever,” he said.

McLaughlin sharply criticized the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) and its leader, Col. Steven McCraw. The Texas Rangers, a DPS agency, are leading the investigation into the shooting and McLaughlin told residents he was upset that he and other city officials have never been briefed on how the investigation is going. He went on to say he thinks McCraw is making misleading statements to help distance the actions of the state troopers and Texas Rangers who responded to the shooting.

“Colonel McCraw has continued to, whether you want to call it … lie, leak, mislead or mistake information in order to distance his own troopers and Rangers from the response. Every briefing he leaves out the number of his own officers and Rangers that were on scene that day,” McLaughlin said.

Earlier in the day, McCraw appeared in front of Texas lawmakers, slamming the law enforcement response to the massacre and harshly criticizing the decisions of Uvalde school district police chief Pedro “Pete” Arredondo.

“There is compelling evidence that the law enforcement response to the attack at Robb Elementary was an abject failure and antithetical to everything we’ve learned over the last two decades since the Columbine massacre,” McCraw told the Texas Senate Special Committee to Protect All Texans in Austin.

“Three minutes after the subject entered the West building, there was a sufficient number of armed officers wearing body armor to isolate, distract and neutralize the subject,” he continued. “The only thing stopping the hallway of dedicated officers from entering rooms 111 and 112 was the on-scene commander, who decided to place the lives of officers before the lives of children.”

Arredondo, who has not spoken in a public capacity since the incident, testified Tuesday behind closed doors to the committee. The recently sworn in council member was not present at the meeting where the other members voted unanimously to deny him a leave of absence from future sessions.

McLaughlin told residents in the meeting room he was angry that he couldn’t get the community answers to the questions they have and said he has no allegiances to anyone, noting he cannot run for mayor again.

“The gloves are off,” he said. “As we know (information about the investigation), we will share it. We are not going to hold back anymore. We kept quiet at the request (of other agencies) because we thought we were doing a formal investigation and doing the right thing.”

The mayor said he requested body camera video from all agencies that responded to the shooting and hasn’t received any.

Questions remain about what happened between first and final shots

On May 24, the gunman with an AR-15-style rifle entered two adjacent classrooms at 11:33 a.m. and killed 21 people before a standoff with police. The gunman remained inside the classrooms – even as children inside called 911 and pleaded for help – until law enforcement finally entered the rooms and killed him at 12:50 p.m., according to a timeline from the public safety department.

What happened within those 77 minutes has remained unclear as Texas officials offered conflicting narratives of the response.

McCraw’s comments Tuesday represent the first time an official has provided substantive information on the shooting in weeks. He said that the decisions to wait contradicted the established active-shooter protocol – to stop the suspect as quickly as possible.

“The officers had weapons, the children had none. The officers had body armor, the children had none,” McCraw said. “The post-Columbine doctrine is clear and compelling and unambiguous: stop the killing, stop the dying.”

The public safety department’s timeline indicated that 11 officers arrived at the school, several with rifles, within three minutes of the gunman entering the classrooms. The suspect then shot and injured several officers who approached the classrooms, and they retreated to a hallway outside the rooms. The group of officers then remained in the hallway and did not approach the door for another 73 minutes.

“While they waited, the on-scene commander waited for a radio and rifles,” McCraw said, referring to Arredondo. “Then he waited for shields. Then he waited for SWAT. Lastly, he waited for a key that was never needed.”

Arredondo had previously told the Texas Tribune he did not consider himself the incident commander that day. However, at least one of the officers is noted at 11:50 a.m. expressing the belief that Arredondo was leading law enforcement response inside the school, telling others, “The chief is in charge,” according to the public safety department’s timeline.

Despite the criticisms, McCraw expressed discomfort in calling out Arredondo individually. “I don’t like singling out a person and shifting and saying he’s solely responsible, but at the end of the day, if you assume incident command, you are responsible,” McCraw said.

Officers did not try to breach doors for over an hour

Late Monday, reporting from CNN, the Texas Tribune and the Austin American-Statesman previewed some of the DPS timeline and revealed further flaws in the police response.

In the initial days after the shooting, authorities said the suspect had barricaded himself behind locked doors, preventing outgunned responding officers from stopping him sooner.

Arredondo, who has been identified by other officials as the incident commander on the scene, had previously told the Texas Tribune that officers had found the classroom doors were locked and reinforced with a steel jamb, hindering any potential response or rescue. Efforts were made to locate a key to unlock the door, he said.

However, McCraw said video evidence showed no one ever put their hand on the door handle to check whether it was locked. Further, the doors at Robb Elementary were not able to be locked from the inside, McCraw said, calling it “ridiculous” from a security perspective. McCraw also said that one of the classroom doors was not functioning properly. “This door … was unsecured. Whether it was locked or not, it was unsecured because the strike, the throw, did not fit correctly into the strike plate,” he said.

In addition, Arredondo initially said that the responding officers needed more firepower and equipment to breach the doors. For example, at 11:40 a.m., Arredondo called the Uvalde Police Department’s dispatch by phone shortly after the gunman fired at officers and requested further assistance and a radio, according to a DPS transcript.

“We don’t have enough firepower right now, it’s all pistol and he has an AR-15,” Arredondo said, according to a DPS transcript.

However, two of the first officers to arrive to the scene had rifles, according to McCraw.

In the first minutes of their response, an officer also said a Halligan, a firefighting tool that is used for forcible entry, was on scene, according to the timeline. However, the tool wasn’t brought into the school until an hour after officers arrived and was never used, the timeline said.

One security footage image obtained by the Austin American-Statesman shows at least three officers in the hallway – two of whom have rifles and one who appears to have a tactical shield – at 11:52 a.m., 19 minutes after the gunman entered the school.

In all, officers had access to four ballistic shields inside the school, the fourth of which arrived 30 minutes before officers stormed the classrooms, according to the timeline.

CNN has reached out to Arredondo’s attorney, George Hyde, and the Uvalde Police Department regarding the reports.

CNN’s Rosalina Nieves, Dakin Andone, Travis Caldwell and Dave Alsup contributed to this report.