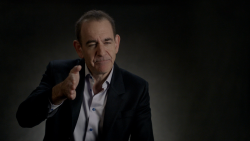

“It’s a story we shouldn’t forget.” Fifty years later, that’s how John Dean, the former White House counsel whose marathon testimony before the US Senate’s Watergate Committee tipped the dominoes toward the ultimate resignation of President Richard M. Nixon, describes what happened to him, the people he worked with and the American people following the June 17, 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office building in Washington, DC.

Having tried and failed to convince his boss that the Watergate scandal was, as he famously put it, a “cancer” for the American presidency that was “growing daily,” Dean – who knew he had been set up to take the fall for the corruption – realized, “I’m going to be the one who has to blow this all up.”

In some ways, the notion that Americans “shouldn’t forget” Watergate could come off as sounding facetious. In the years since the break-in, thanks in large measure to the now-legendary reporting done by then-Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, Americans have utterly consumed the story of Watergate, whetting a voracious appetite across the decades with in-depth tell-all books, documentaries, television series, film adaptations and podcasts.

There’s virtually no other story related to the US presidency with more currency in American culture. For generations, appending “-gate” to a noun has served as an internationally recognized (and occasionally mocked) short-hand for corruption and the abuse of power.

If we can’t stop re-reading and re-telling a story, how can it be forgotten?

Far too easily, says Dean in the CNN documentary series “Watergate: Blueprint for a Scandal,” which marks the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in but also draws crucial parallels between what happened then and what’s unfolded in American politics in the 21st century.

Dean, 83, spoke with CNN Opinion about his thoughts on Watergate, 50 years later. “I don’t wallow in Watergate anymore,” he said, but he also believes contemporary events make it more imperative than ever to “let people remember what the core story was.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

CNN: Fifty years after Watergate, what has America learned?

John Dean: I’m not sure they’ve learned anything at all. For a while, it was clear Watergate had an enormous impact. For about a decade, because there was something they actually called a post-Watergate morality. And that ran through a couple of presidencies.

By the time you get to the Bush-Cheney years, the president is trying re-capture all lost powers that occurred during Watergate. And it’s been a pretty steady increase (of presidential power), ever since the Bush years. So, I’m not sure (the American people) learned anything about potential (risk) of an overly powerful president.

There have been segments of our public life that have been more affected (by Watergate) than others. For example, journalism has been deeply affected. Pre-Watergate presidents were really given the benefit of the doubt (by the media). Post-Watergate, they’re pretty much assumed to be guilty, they have to establish their innocence. I can’t think of a more moral president than Jimmy Carter. But he was plagued by scandals. Even he was not given the benefit of the doubt.

CNN: Does this anniversary feel different to you from the others? If so, how?

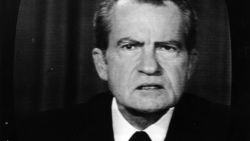

Dean: It feels different to me because of the Trump presidency. I don’t think you can look at Watergate today without looking at what happened during the Trump years. And that actually makes Richard Nixon look pretty good by comparison. Nixon, it was obvious to me, had a conscience. He experienced shame. Did he abuse power? You bet. But at least he had some internal checks on himself. I’m not sure that Donald Trump does.

I never really felt worried during Watergate that small “d” democracy was in any trouble. But I can tell you, from the time Trump was nominated, until he left, that I had a knot in my stomach. And unfortunately, his departure didn’t end the problems that he triggered, if you will. That’s why to me, doing the documentary series was important. I think it was important to tell that story from a 50-year perspective.

CNN:What do you hope people take away from the 50th anniversary of Watergate right now, especially during an election year?

Dean: I hope they remember that Americans can learn when things are out of whack with democracy, and they’re really out of whack now. I hope this will encourage Americans to want to get to the bottom of what’s wrong with democracy, with issues like January 6.

What’s wrong is not just a few degrees, but many degrees worse than what happened during Watergate with Nixon’s abuses. I mean, it’s sort of where Nixon’s abuses could have taken us. To where a president is literally saying I don’t care what the electorate says, I’m going to stay and I’m going to rig the system so that I can pretend I’m president.

We learned some lessons for a while, but every post-Watergate norm has been shattered by Donald Trump.

CNN: What do you think about former Trump administration officials publishing books sharing what they were hearing or were being exposed to, doing it belatedly instead of knowing something is wrong and calling it out at the time?

Dean: I’m not surprised they’re doing what they’re doing, because there’s a market for that information. I had book offers literally within hours of my testimony before the Senate. I think if anyone has information for the January 6 committee, and if they’re not giving it to them, it’s beyond “shame on you.”

CNN: What aspects of Watergate do you wish got talked about more. What’s gotten lost?

Dean: What’s gotten lost? The incipiency of our polarization was evident during the Watergate years. There was a sharp division between left and right, but it took time for people to realize it was serious. Over time, I think we’ve lost our ability to react.

Today, if one camp says it, the other camp just says the opposite. They take a visceral reaction to things. During Watergate, people slowly got educated to the facts of what happened. Yes, there have been efforts to do revisionism on Watergate, but it hasn’t worked, because the record is just so overwhelming.

CNN:There’s such a tendency to compare scandals, political and otherwise, to Watergate. Have there ever been moments where you just sat up watching the news at home and said to yourself, “Oh my god, it’s the Saturday Night Massacre” or “It’s the tapes, all over again?”

Dean: I did do a book called “Worse Than Watergate,” about the Bush-Cheney years, provoked by their effort to expand presidential powers, their extreme secrecy. What capped it off and put the “worse” label on it was when they authorized torture (as part of the War on Terror). I can’t envision Nixon, not even in his darkest moment – as a World War II vet, who served in the South Pacific where I think he’d probably seen some waterboarding – ever authorizing that. I did think, after the Trump people arrived, that I might have spent that title too early.

CNN: The Trump era reconfigured the Bush years for a lot of people.

Dean: I’m stunned by the (evolution of the) Republican Party, that any kind of check or balance on conservative radicals just vanished.

CNN: One thing that comes out very clearly in the series is seeing all of these Republicans, none of whom were necessarily in ideological or political lockstep with each other, unify as a cohort, letting Nixon know that for him, this is over.

Dean: There’s no question that it was a slow process, but in the end, there was unanimity in the Republican ranks that Nixon had to go.

CNN: Speaking in the series about your involvement in Watergate, you said, “I didn’t want to think about what I was doing, so I didn’t dwell on it.” What allowed you not to think about it? And what ultimately changed your mind?

Dean: You’re asking me, personally, why did I ignore what was going on? It was instructed from the top and nobody was paying any attention to it. It was very easy to ignore. It wasn’t affecting the presidency or the reelection campaign or what have you. I didn’t think we were doing anything criminal.

When I went to John Ehrlichman, my predecessor, to tell him I thought we should hire someone with a criminal background for my staff, he just absolutely dismissed it. Would not hear of it. Did not want outside lawyers. I was going to bring somebody over from the Department of Justice so we didn’t make any mistakes, but he shot that down instantly. And I don’t know if that was part of the (strategy that) “we’re not going to play this up” or if he genuinely believed we wouldn’t make mistakes or what. But we made every mistake you can make.

It’s not until I hear about the (Chuck) Colson/(E. Howard) Hunt conversation (shortly after Nixon’s re-election, Hunt, who had helped organize the Watergate break-in, was demanding money from Colson, Nixon’s special counsel), where he’s recorded Hunt – that’s where the bell rings, and I know we’re in trouble. And I was just recently married.

CNN: Why were you convinced that you could persuade your White House colleagues to end the coverup, or to take a different path?

Dean: Initially I didn’t realize how big a problem we had. It’s not until I looked up “obstruction of justice” that I realized we were deep into it. I did go to Ehrlichman to tell him right away. I said, “John, I have a copy of the statute” – you know, a Xerox that I had personally done myself. They had little bays around the halls, and you could go in and use the Xerox machine. And I just laid the law book down, took a picture of it, and walked over to Ehrlichman’s office and showed him the statute.

And his argument to me was, “Well, I see that statute, but it doesn’t trouble me, because I have no criminal intent.” And I thought, “Here’s a guy who went to school with William Rehnquist and Sandra Day O’Connor and he’s telling me he has no criminal intent? He missed class that day.” He certainly intended to do the things he was doing.

CNN: But it sounds like, from what you’re describing, you had this belief that “I have this Xeroxed statute in my hand, I know the law, the law is on this page in black and white, and once I show it to X person, surely, you know, there’ll be some sort of realization or, action taken to address it.” And that turned out not to be the case.

Dean: Exactly. And at that point, I thought, “If they’re not worried, I won’t be worried either. But I gotta make this coverup work now.” And that’s why I have never said I wasn’t violating the law. There is a long phase where I had no knowledge that I’m violating the law, but when I do, I realize there’s just no question in my mind that I was breaking the law.

It’s kind of an esoteric law, in a way, because you can obstruct justice in so many ways one would not think about. But Watergate put obstruction of justice on the map.

CNN: There was this long moment, before a lot of others came out against Nixon, where you really stood alone against an American president. What was that like?

Dean: It was lonely. My disappointment was being unable to get him to see it my way, when we were talking (in a conversation recorded on March 21, 1973) about Watergate being a “cancer close to the presidency,” when we’re just talking outright criminal behavior. That’s really the day I met Richard Nixon.

Particularly once it was confirmed there was a taping system, I had some confidence that it wouldn’t be my word against Nixon’s forever. That is, unless he had a bonfire on the South Lawn – that was my only anxiety, that we would have a constitutional crisis if he just blatantly destroyed evidence. But after the Saturday Night Massacre, I didn’t feel so lonely. I felt like a lot of people want to get to the bottom of this and it’s going to come out eventually.

The short answer to your question, which is a fair question, is: I didn’t think I would be standing alone. I was pretty comfortable, once the taping system was discovered, that Nixon would never be able to keep it indefinitely buried. I thought either Congress would go after these conversations, or Nixon would appoint another prosecutor. And that’s what happened.

CNN: What would you most like to change or have done differently about your time in the Nixon administration?

Dean: Taking the job in the first place. I did try to leave the White House at one point, I went into tell (Chief of Staff H. R.) Haldeman I was resigning and he, in essence, told me I would be persona non grata if I left, he’d make sure of it.

I would have left if I had been smart. Haldeman said, “You’ll get better offers when Nixon’s re-elected,” and at the time, I couldn’t dispute that. But I should have seen enough at that point. I didn’t really fit in with them. I should have acted on that, but I didn’t.

And when you’re in your early 30s, you don’t exactly know where your boundaries are, either. I do recall thinking many times back in those years, Maybe I am just na?ve and don’t understand how it’s played in the big leagues. And here I am, and I’m watching what happens in the big leagues.

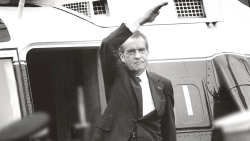

CNN:You said in the series that you felt no vindication in Nixon’s resignation. Why?

Dean: I guess it’s the nature of who I am. I was trying to resolve a problem, and I didn’t. For a long time, I tried to encourage Nixon to get in front of it, and be the one who resolved it himself, that he would get credit for that. But I failed at every effort, down to the point that we’re really at war. He’s trying to destroy me, as a witness. And he lost. And I don’t feel vindicated by that.

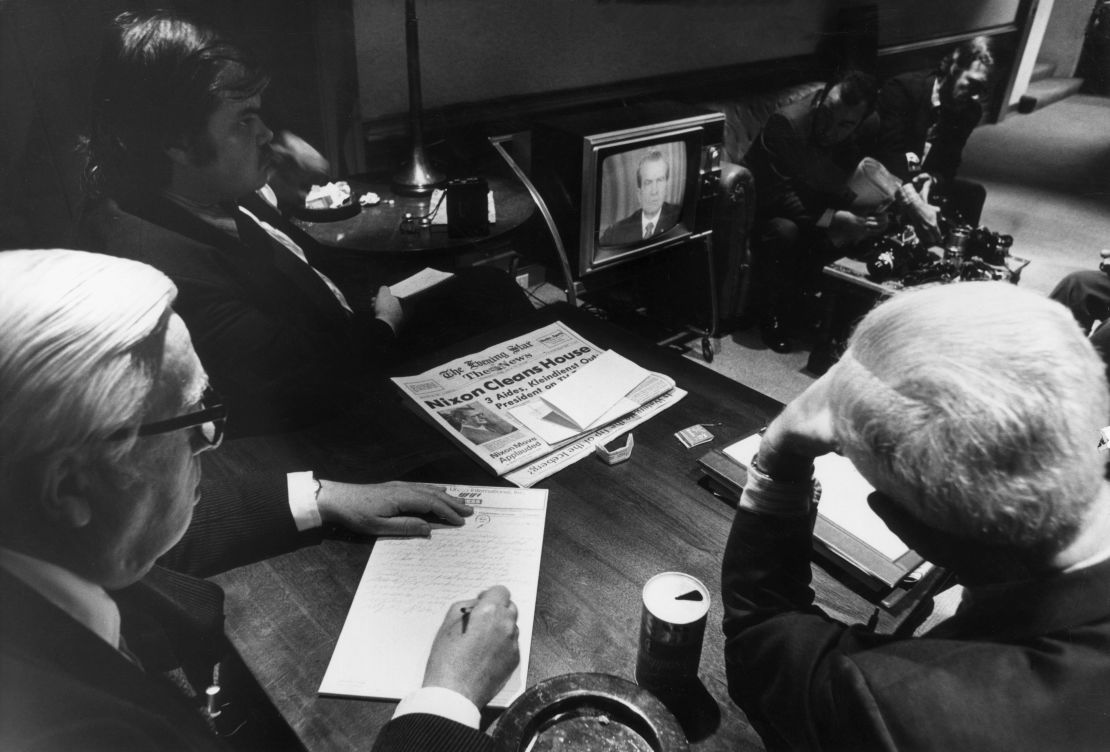

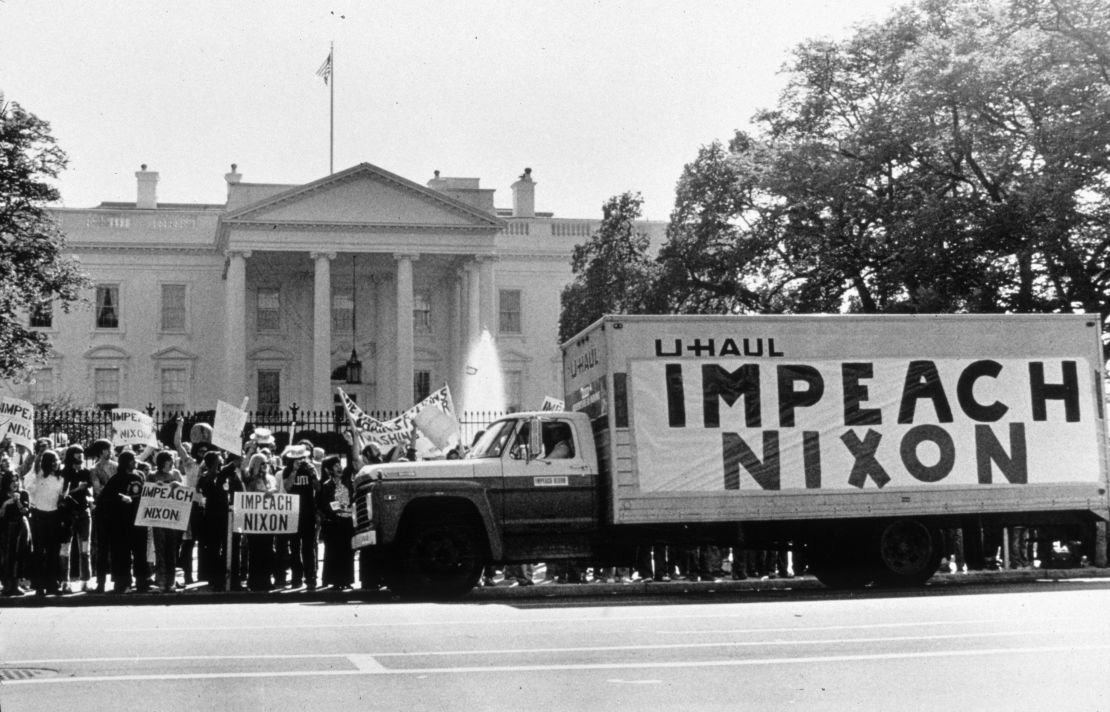

In pictures: The Watergate scandal

He made all the mistakes he had made before we got into that fight, but he compounded them. Here’s a man who had deep legal problems, and he wouldn’t tell his lawyers what was going on. It’s just typical of Nixon, never getting the best advice, because he wouldn’t even tell his lawyers his problems.

The lawyers learned about the taping system because of my testimony before the Senate, where I say I think I’m taped. Nixon didn’t want his lawyers to even have the facts. So when you look at the big picture, vindication was just something I never felt.

CNN: How did you feel about Nixon by the end of his life, or any of the men who orchestrated these events? What do you think about when you remember them?

Dean: At some point, Nixon realized how poorly he had been served. He realized I was actually trying to warn him, but I was not surprised he was not sending Christmas cards (laughs) after he headed back to San Clemente, and then up to New Jersey.

I ran into Haldeman once and he said, “Let’s get together for lunch.” And I said, “Good idea.” But I didn’t get back to him soon enough – a few weeks later, he was dead. He had cancer. I also ran into Ehrlichman, at my publisher’s reception area. I had an appointment with my editor. I walked in and I heard this voice in the back saying, “Hello, John.” And it was John Ehrlichman. I went and sat down and visited with him, and he was called in before I was, and I never saw him again until I deposed him during one of my lawsuits. And he was very bitter as I was deposing him. Lots of snide, nasty comments. But I retained a lot of friends from that era as well. Alex Butterfield, who you see in the series, is 96, and has still got it all together. And I think Alex is going for 100, if not 100-plus.

CNN: I’ve always been struck by the obsession in American popular culture with revisiting and re-portraying the events of Watergate. The pop culture of Watergate could be its own syllabus –

Dean: (Laughs)

CNN: Where do you think this hunger to re-interpret or re-create it comes from?

Dean: That’s an interesting question, because I never thought I would be stuck in this (Watergate) bubble, for life. I tried to get out of it, and it wouldn’t let me out. I don’t know the reason that it appeals to people. A lot of young people were struck by it, as it was happening. Some of them went on to become academics, and they say the lessons that could be drawn from it.

Across the academic spectrum, Watergate literally changed legal education; (in sociology and political science) it altered the study of scandal. At one point, I considered doing a book called “The Rules of Scandal.” My editor talked me out of it. “John,” he said, “you’d be writing a how-to book. You shouldn’t write that.” But as to the cultural appetite for Watergate, I just don’t know the answer.

CNN: So then I guess you don’t have a favorite among the books, films, shows or podcasts out there?

Dean: I haven’t seen them all (laughs)! It’s just too much material to pick a favorite. I haven’t watched “Gaslit” (the recent Starz series that spotlights Martha and John Mitchell), but people say to me – which I’m pleased to hear – that my wife comes out as a very good character. And she would, because she is. She’s a really good person. But people also told me, “The portrayal of you is not close, but it’s good storytelling.”

CNN: Why do you think Watergate has remained such a durable metaphor for malfeasance by people in power?

Dean: I think because of Nixon’s resignation. It showed an absolutely clear level of what’s unacceptable behavior to the American people: the abuses of power, known and unknown, were more than Americans thought was appropriate for their president. But what’s strange is how quietly those abuses have crept back into the system and are now ignored.