Kitchen sponges harbor more bacteria than kitchen brushes, which may be a more hygienic way to clean your dishes, according to researchers in Norway.

“Salmonella and other bacteria grow and survive better in sponges than in brushes, the reason is that sponges in daily use never dry up,” said Trond M?retr?, a research scientist at Nofima, a Norwegian food research institute.

“A single sponge can harbor a higher number of bacteria than there are people on Earth,” said M?retr?, an author of a new study, which published online in the Journal of Applied Microbiology.

While many bacteria are not harmful, those that are – like salmonella – can spread from sponges to hands, kitchen surfaces and equipment and potentially make people sick, he said.

“The sponge is humid and accumulates food residues which are also food for bacteria, leading to rapid growth of bacteria.”

What surprised the researchers most about their findings was that it didn’t really matter how people cleaned their sponge or how often.

“That the way the consumers used their sponges did not matter much regarding growth of bacteria. It is very difficult for consumers to avoid bacterial growth in the sponges as long as the sponges are not replaced daily,” M?retr? said.

The research on the used sponges and brushes builds on a lab-based study published last year by the same team of researchers, which found that harmful bacteria survived better in sponges than in brushes.

In the United States, the USDA said that that microwaving or boiling kitchen sponges may reduce “some of the bacterial load,” however these measures alone are not adequate to ensure your sponge will reduce cross-contamination. It advised to buy new ones frequently.

The research was part of a European Union-backed project on food safety.

Sponge vs. brush

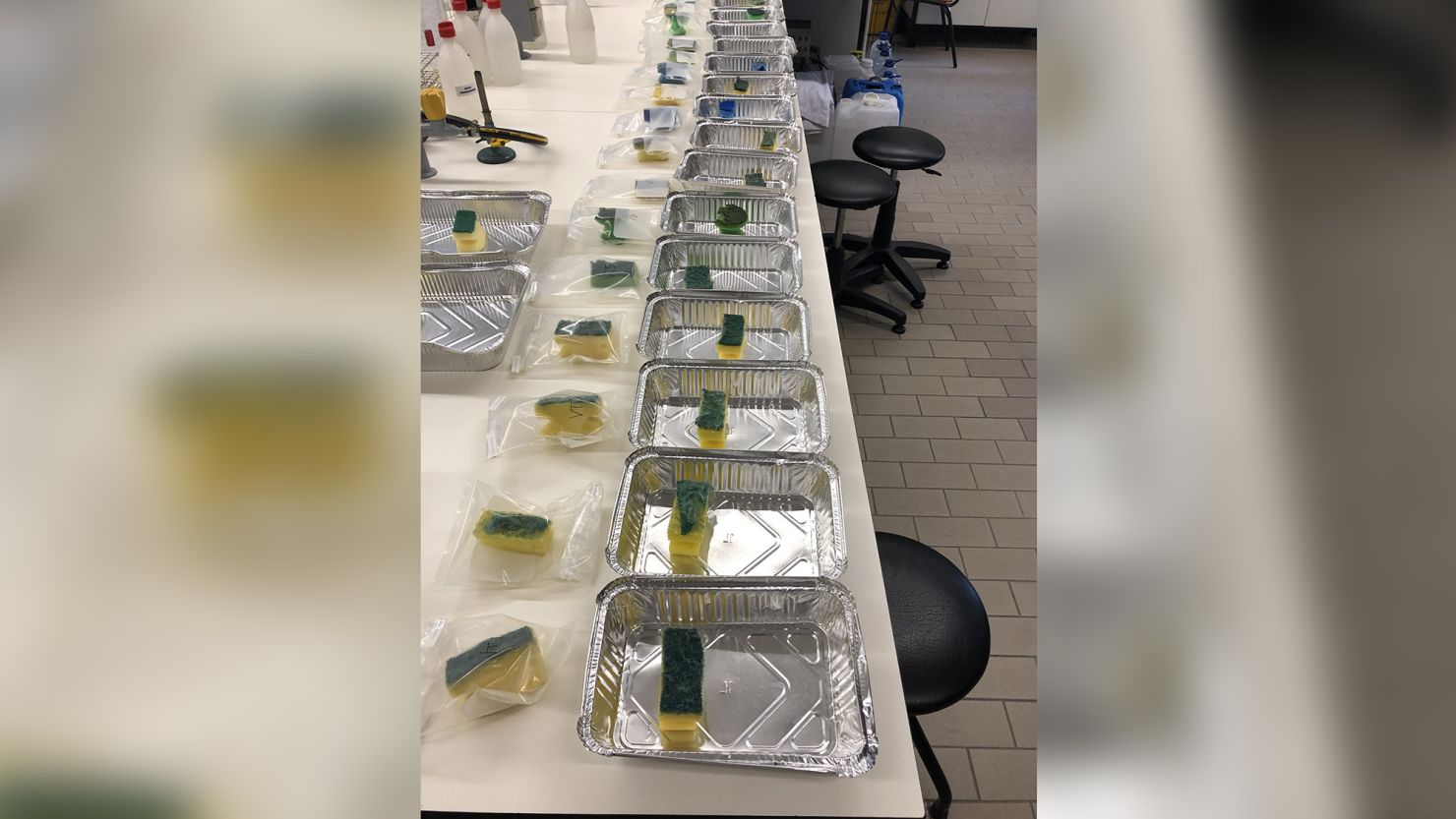

The researchers collected kitchen sponges from 20 people living in Portugal and 35 brushes and 14 sponges from people living in Norway.

An earlier survey of 9,966 people by the research team found that sponges were commonly used for cleaning in kitchens in the majority of 10 European countries, with brushes the dominant cleaning utensil for washing up in only two countries – Norway and Denmark.

The sponges were all used for washing dishes – scrubbing pots and pans, and 19 of the 20 sponges from Portugal were used five to six times a week or more often. Of the brushes collected in Norway, 32 out of 35 were used five to six times a week or more. The sponges collected in Norway were used less frequently.

No pathogenic bacteria (that causes disease) was found in the brushes or the sponges. However, overall bacteria levels were lower in used brushes than sponges. Similar types of non-pathogenic bacteria were found in the two cleaning utensils.

When the researchers added salmonella bacteria to the brushes and sponges, they found a significant reduction in the salmonella numbers in brushes allowed to dry overnight. But there was no reduction for brushes stored in a plastic bag or for sponges regardless of storing conditions.

The owners of the sponges and brushes shared how long they typically used their sponge or brush and how they kept their cleaning utensils clean – rinsing with water, washing with soap and water, placing them in the dishwasher or bleaching.

However, none of these things made a tangible difference – something that surprised the researchers. The key takeaway from the study was that brushes, which dry between use, have lower numbers of bacteria.

“Since the brush dries very fast, harmful bacteria will die. Also, most brushes have a handle which prevents you from direct hand contact with potential harmful bacteria, in contrast to sponges,” he said.

“I encourage consumers to try a brush instead the next time they need to replace their sponge.”

What to do

While study authors recommended the bristles of a brush over the squish of a sponge, Cath Rees, a professor of microbiology at the University of Nottingham who wasn’t involved in the research, she said would continue using a sponge to wash dishes. For her, the key takeaway was that drying dish sponges and cloths between use was a good idea.

“The main message I get is that they did not find any evidence of pathogenic bacteria on the sponges or brushes taken from a range of domestic settings and therefore there is no evidence that these items are a significant source of contamination in normal domestic settings,” Rees said.

“If there were some low levels of pathogens left on your cloth, they are going to grow quite slowly (they grow optimally at body temperatures), so you would not expect to see much growth of these, and this matched their results – in wet condition there was some limited growth, in drying conditions the numbers either stayed the same or declined,” she explained.

Markus Egert, a microbiologist at Furtwangen University in Germany who has conducted similar research, said he already used brushes to wash up his dishes, which he cleaned in the dishwasher. If people preferred a sponge, Egert, who was not involved in this study, recommended using a new one every two to three weeks.

“Brushes are the better choice to clean dishes, from an hygienic point of view. This might have been anticipated before, but the authors prove it with some nice experiments. However, based on my experience people love using sponges.”