Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Ancient poop found at the site of a prehistoric village near Stonehenge revealed that the settlement’s inhabitants – who likely built the stone circle – feasted on the internal organs of cattle.

Several pieces of fossilized poop, which scientists call coprolites, were unearthed from a refuse heap at a settlement known as Durrington Walls, just 1.7 miles (2.8 kilometers) from Stonehenge. The village dates back to around 2500 BC, when much of the imposing monument in southwest England was constructed.

Five pieces of poop – from one human and four dogs – were found to contain the eggs of parasitic worms.

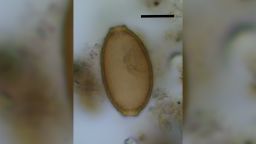

The human poop and three of the dog coprolites contained the eggs of capillariid worms, identified in part by their lemon shape. The presence of this type of worm indicated that the person had eaten the raw or undercooked lungs or liver from an already infected animal, which would result in theparasite’s eggs passing straight through the digestive system, according to a new study on the fossils.

Capillariid worms infect cattle and other ruminants, suggesting that eating cattle was the most likely source of the parasite, the study authors noted. The dogs may have been fed leftovers.

However, bones dug up from the trash heap suggested that cattle weren’t the most commonly consumed animal. Some 90% of the 38,000 bones unearthed were from pigs and 10% from cattle.

One piece of the poop belonging to a dog contained the eggs of fish tapeworm, indicating it had become infected by eating raw freshwater fish. However, no other evidence of fish consumption, such as bones, has been found at the site. This lack of evidence is perhaps because the site wasn’t used year-round, and the fish with the tapeworm was consumed at a different settlement.

“Durrington Walls was occupied on a largely seasonal basis, mainly in winter periods. The dog probably arrived already infected with the parasite,” said study coauthor Dr. Piers Mitchell, a medical doctor and senior research associate and director of the Ancient Parasites Laboratory at the University of Cambridge’s department of archaeology, in a news release.

“Isotopic studies of cow bones at the site suggeststhey came from regions across southern Britain, which was likely also true of the people who lived and worked there,” he said in the statement.

The research was published Thursday in the journal Parasitology.

Stonehenge is made of two types of stone: larger sarsen stones and smaller bluestone monoliths from Wales, which were erected first. Archaeologists believe that Durrington Walls was inhabited by the people who built the second stage of the monument, when the instantly recognizable trilithons – two vertical stones topped with a third horizontal stone –were erected.

The village is also thought to be a site where many feasts took place – as revealed by pottery fragments and the huge number of animal bones found there. However, there is little evidence to suggest that people lived or ate at Stonehenge itself.

“This new evidence tells us something new about the people who came here for winter feasts during the construction of Stonehenge,” said study coauthor Mike Parker Pearson, a professor at University College London’s Institute of Archaeology and the leader of The Stones of Stonehenge research project.

“Pork and beef were spit-roasted or boiled in clay pots but it looks as if the offal wasn’t always so well cooked.”

![? Nebra Sky Disc, Germany, about 1600 BC. Photo courtesy of the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták

Rights to reproduce the above image(s) are hereby granted for the use once only for the specific purpose (promotion, criticism or review of the exhibition "The world of Stonehenge" in ... [mention magazine, journal, newspaper, website etc.]). No other usage is permitted.

Any further use or reprint of the image must be applied for again separately in written form.

Please do not store the electronic data further than the named use and do not pass it on to any third party.

Credit must be given to the "Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Arch?ologie Sachsen-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták" ("State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták"). The official abbreviation is "LDA Sachsen-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták".](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/220215100813-09-stonehenge-british-museum-handout-restricted.jpg?c=16x9&q=h_144,w_256,c_fill)