When a trade jumps by 250% over the course of days, investors typically pop bottles of champagne. Between Friday, March 4 and Tuesday March 8, nickel futures did just that — soaring on the London Metal Exchange from about $29,000 to $100,000 per ton. But the champagne remains corked, investors are threatening to sue and the LME is hemorrhaging business.

So how did it happen?

The tale that ensues involves billions of dollars, Russia, a Chinese tycoon known as “Big Shot,” daytime drinking and a metal exchange stuck between two large rocks without a chisel.

A sleeping giant awakens

For the majority of the last decade, nickel prices were boring. On the London Metal Exchange, the premier trading and price-formation venue for industrial metals, nickel traded between $10,000 and $20,000 per metric ton and moved about $100 each day.

Then in early March a short squeeze of epic proportions, prodded by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, awoke the sleeping giant.

One Chinese metals producer, Tsingshan Holding Group Co., sat at the center of the storm. The group had wagered a massive bet that the price of nickel would fall. At its peak, Tsingshan’s short position was equivalent to about an eighth of all of the outstanding contracts in the market: If prices had stood at $100,000 the company would have owed the LME $15 billion, according to the Wall Street Journal.

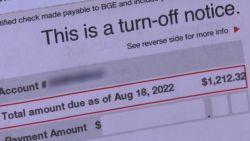

The spike generated margin calls higher than the LME had ever seen — and if paid, they would force multiple defaults that would ripple through the exchange and destabilize the global market.

Exchange executives scrambled to respond, ultimately throwing a lifeline to the brokers representing Tsingshan and other producers. In an unprecedented move, they halted trading and retroactively canceled all 9,000 trades that occurred on Tuesday, worth about $4 billion in total.

The market would remain dark for a week, unleashing a tidal wave of chaos and a mob of angry investors onto the exchange. In its wake, threats of lawsuits abound and trust has eroded.

Now, the 145 year-old British giant is teetering on the edge of a nickel.

Kicking and screaming into the 21st century

Over the past century-and-a-half the LME, known for its ring of red couches and barking brokers, has successfully trudged its way through world wars, meltdowns and defaults. But nickel, the metal used in stainless steel and the lithium-ion battery cells in most electric vehicles, might be what finally brings the world’s largest market for base metals contracts to its knees.

“The world’s pricing mechanism for nickel is failing,” said Daniel Ghali, the director of commodities strategy at TD Securities. “The question is, will it continue to fail?”

Others weren’t as diplomatic. “The LME is now very likely going to die a slow self-inflicted death through the loss of confidence in it and its products,” tweeted Mark Thompson, executive vice-chairman at Tungsten West, a mining development company.

The LME functions as a utility for metals producers, setting the price at which they sell their goods to various businesses and serving as a way to hedge against downturns in their industry. Other investors see it primarily as a money-making tool, a part of a well-balanced portfolio. The exchange needs both parties to function, but underlying problems are ready to boil to the surface.

Unlike stock exchanges, the LME deals in physically deliverable contracts: There are actual, nickel-backing trades that will be delivered. For most of its history, that served the miners, traders and manufacturers well.

But in recent years the exchange has been pushed to start moving into the 21st century. Until 2012, the LME was owned by its members, the same people who traded on the exchange — but then it was sold to Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX) for $2.2 billion. The new owners raised fees to recuperate some of their investment, upsetting the community. Volumes dropped significantly, and the chief executive and operating officer left.

So the LME wooed a new class of customer to bring volumes back up: hedge funds, and other major financial players.

Big money flooded in. The reform part, however, didn’t go as well.

“When I joined the LME floor in the late 1970s, it was very much a ‘my word is my bond’ type of place,” said John Browning, the managing director of BANDS Financial who served as a board member of the LME and the chairman of its e-commerce committee between 2002 and 2004. “There were probably as many deals done on the floor as there were in the pub next door.”

Indeed, LME traders became famous for some very boozy lunches.

“I have seen the floor in the afternoon and there are those who overdo it,” veteran trader Malcolm Freeman recalled to the Financial Times.

But as trading surged, so did concern that boozed-up brokers would fumble away investors’ cash.

In 2019, the LME officially banned daytime drinking and required that traders remain sober on the floor. The exchange also issued a code of ethical conduct after it was criticized for hosting a cocktail party at The Playboy Club.

More technical changes were also proposed.

In 2021, LME CEO Matthew Chamberlain attempted to get brokers to agree to clearer reporting on over-the-counter transactions: off-exchange trading that’s done directly between two parties without the supervision of an exchange. This kind of disclosure is common on exchanges, but brokers on LME said the reports were too complex and costly and blocked the proposal.

That fatal decision could be what marks the end of the exchange.

Winners and losers

The LME’s lack of transparency allows two or three big names to throw around vast sums of money and “hijack” a relatively illiquid market, said Adrian Gardner, principal analyst of nickel markets at Wood Mackenzie.

When Tsingshan got caught in its short squeeze, it held 30,000 tons of its position on the LME, another 120,000 tons were held in over-the-counter positions with banks like JPMorgan (JPM), BNP Paribas, Standard Chartered and United Overseas Bank.

“The LME was ill-informed as to the size of the positions in the market, and they didn’t know it was all concentrated in one hand,” said Browning. “The LME didn’t know that there was one company sitting on the other side of this with a 150,000-ton short.”

Sitting on the other side of the short were hedge funds, who had bet that nickel supply would decrease because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Russia provides about 20% of all top-grade nickel). When the LME decided to retroactively cancel those $4 billion in gains on March 8, it was hedge funds who lost giant sums of money.

Global investment management firm AQR, which has $124 billion in assets under management, was among those that lost money when trades were canceled.

“The winners were commodity producers and their banks, and the losers are the various clients that AQR and other large asset managers represent: firefighters, municipal workers, and university endowments,” said Jordan Brooks, principal at AQR Capital Management. AQR is considering legal action against the exchange.

Investors, said Brooks, “acted in good faith and provided liquidity, but the LME just decided to shift their trading gains to commodities producers and their banks.”

Still, it’s hard to say that the producers who used margin accounts to borrow money from brokers to short nickel — and now owe billions — are winners.

The LME is a massive enterprise. The equivalent of 3.5 billion tons of metal is traded annually and a global standard for pricing these essential elements is set and moderated by the exchange. If it were to cease operations for an extended period, it would likely create a black hole for metals manufacturers and dealers around the world.

Big Shot

Tsingshan is led by metal tycoon Xiang Guangda, known in China as “Big Shot.” He began his career making frames for car doors and windows in Eastern China and went on to develop new groundbreaking methods of producing nickel and steel, paving the way for Tsingshan to become the world’s largest producer of the metals.

Xiang’s company has invested billions of dollars in extracting from countries with seismic nickel reserves like Indonesia. Last year, as prices for nickel began to grow based on an increase in demand and limited availability, he began increasing his short.

Some analysts speculated that Xiang wasn’t just looking to short his position, but he was also making a risky bet that his reserves would soon flood the market and lower the price of nickel. The choice was particularly risky because Tsingshan doesn’t produce Class 1 nickel, the only type of nickel the LME accepts. That means there was no immediate physical delivery path for the company to escape through, instead, to stay solvent, they had to work out a deal with the banks who lent them money,

The LME has insisted that their choice to alter the market price on Tuesday was not a bailout for Tsingshan. The exchange also poin ted out that a number of other smaller LME-member brokerages would have also gone bankrupt, triggering a crisis that could shock the industry globally.

The canceling of trades isn’t unprecedented, but it typically happens when there’s a “fat finger” error or fraud is discovered. In this case, the trades were made legitimately and agreed to by both parties. While the LME guidelines technically allow them to cancel the trades, analysts and brokers said they had never seen anything like this happen before.

“It’s strange and sad,” said Gardner. “It’s not good for the LME or the metal industry. It’s not good for the principle of trading or for the principal of free market economics.”

A spokesperson for the LME said that the coexistence of its physical and financial participants helps ensure deep liquidity and benefit the market as a whole but countered that the market had become disorderly and action needed to be taken.

“It became clear in the early hours of [March 8] that nickel prices on the LME no longer reflected the underlying physical market,” the spokesperson said.

The decision to suspend and cancel nickel trades “was taken to preserve the systemic integrity of the market and to prevent disorder.” At all times “we sought to act in the interests of the market as a whole.”

End of an era

A week after trading was suspended, Tsingshan announced it had reached a standstill agreement with JPMorgan and that it would be allowed to maintain its short agreement. The company plans to produce 850,000 tons of nickel this year.

The LME, meanwhile, continues to struggle. Trading of nickel resumed on March 16 with a hard limit set at 5% above or below the last closing price. The limit was hit and trading suspended within a minute of opening.

The suspensions continued on as trading remained volatile. Between March 16 and 25, official closing prices were declared “disruption events” six times.

Volume in trading has yet to recover, raising questions about the LME’s ability to accurately benchmark the price of the metal. Fewer than 210 contracts were traded in the first hour after the market opened on Tuesday. That’s down about 60% from the 90-day average before the trading halt. Other metals on the LME, like copper and aluminum, have also seen a decrease in trade volume.

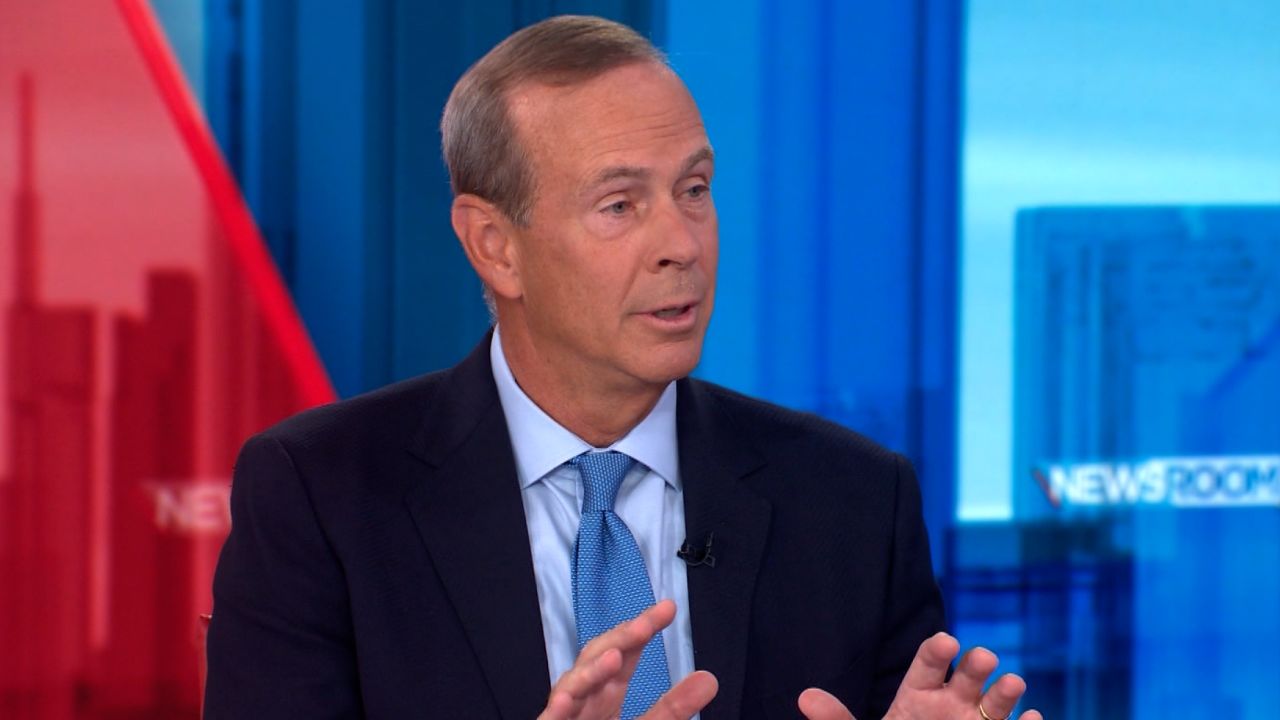

“In terms of the way forward of course, the LME board is responsible for understanding the full impact on the market, and what actions can be taken,” said HKEX CEO Nicolas Aguzin to media after an investor day Tuesday. “I’m sure the board of the LME will take the necessary steps to evaluate what are the lessons learned and how we can continue improving the market structure of the commodities market.”

An LME spokesperson said that beyond instituting price limits, the exchange had also improved its visibility and reporting of on-exchange and over-the-counter client positions. “We fully recognize the frustration of some market participants,” they said. “We are carefully considering future steps.”

Many traders have lost faith in the exchange and are looking to take their business elsewhere, but the question is where.

“There is no alternative at the moment,” said Nikhil Shah, principal analyst of base metals at CRU Group. “There isn’t another choice out there.”

Some are looking to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Shanghai Futures Exchange instead. But traders need an affiliation with a Chinese entity to trade on the much smaller Shanghai Futures Exchange, and differences in currency and language are difficult to overcome. The CME doesn’t currently trade nickel, but perhaps it soon will.

“[The LME] did something that was egregious and a betrayal of trust,” said Brooks. “I’d be shocked if the strategic plans of other exchanges haven’t changed in the past three weeks.”