Editor’s Note: Shane Cronin is a Professor in Volcanology at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He has published more than 200 scientific papers on the chemistry and physics of active volcanoes and strives to understand the hazards they pose, especially in the Asia-Pacific region. The opinions expressed here are his own. View more opinion at CNN.

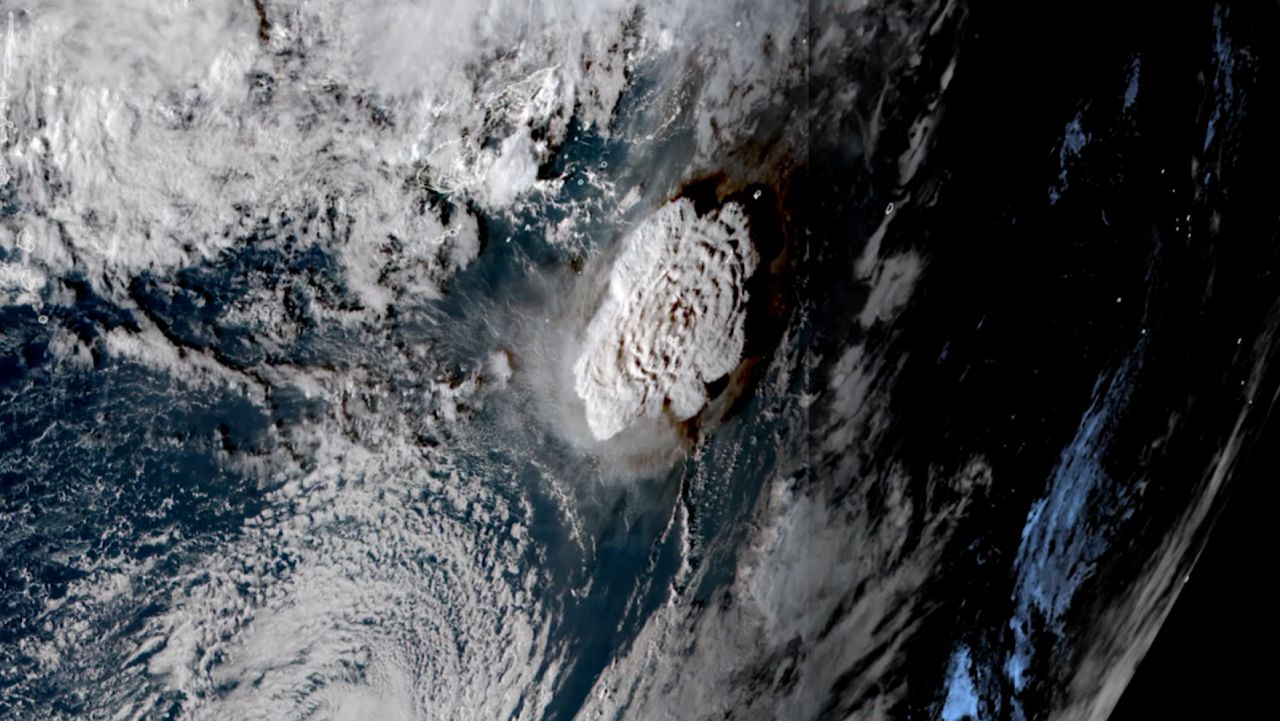

The eruption of the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano on Saturday was so large, it was a spectacle best appreciated from space.

The eruption was remarkable in that it involved the simultaneous formation of a volcanic ash plume, an atmospheric shock wave and a series of tsunami waves.

While details are still emerging and we are still within an eruption episode that could have more twists and turns, there are several pieces of information that can help us begin to understand this event and why it occurred.

First, let’s look at the eruption. Events of this magnitude occur roughly once a decade around the world, but for this volcano an eruption of this scale is a rarity. Based on my research, using radiocarbon dating to examine the ash and deposits from past eruptions, it seems this latest eruption is a once-in-a-millennium event for the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano.

It takes roughly 900-1000 years for the Hunga volcano to fill up with magma, which cools and starts to crystallize, producing large amounts of gas pressure inside the magma. As gases start to build up pressure, the magma becomes unstable. Think of it like putting too many bubbles into a champagne bottle – eventually, the bottle will break.

As the magma pressure rises, the cold and wet rock above the magma fails and suddenly releases the pent-up pressure. The eruption we saw on Saturday blasted rock, water, and magma 30 km high into the atmosphere, and was profound in terms of its energy. Within 30 minutes, the resulting cloud seen from space was over 350 km (or 218 miles) in diameter, with ash falling out onto several Tongan islands.

As for tsunamis, they are most commonly caused by earthquakes. When tectonic plates shift under the ocean, it can displace enough water to cause massive waves. So how does a partially submerged volcano in the southwest Pacific create enough energy to produce tsunami waves that hit the West coast of the US?

While it’s still unclear what exactly caused the tsunami, there are at least two distinct possibilities – and the first has to do with the expansive force of the initial eruption. On Saturday, the eruption of magma from the volcano created a sudden release of pressure, producing supersonic air pressure waves that could be seen from space.

These air pressure waves traveled more than 2000 km (1,200 miles) to New Zealand and were felt as far as the United Kingdom and Finland.

The atmospheric waves and the initial blast affected the ocean surface, causing the giant waves that then hit the Tongan island of Tongatapu and the capital of Nuku’alofa. Early videos showed the waves splashing over roads before the plume of ash darkened the sky.

Another possible cause of the tsunami waves could have been the remarkable changes within the Hunga volcano. In the aftermath of the eruption, images from satellite radar imagery show the central part of the volcano which previously rose above sea level has since disappeared below the waves. This indicates when the eruption occurred, the sudden loss of magma likely caused the central portion of the volcano to collapse, creating a caldera, or a hollow depression. This collapse could have displaced the water, generating tsunami waves that radiated outwards across the Pacific and all the way to California.

The Hunga eruption was also astounding in terms of all the lightning generated. This is caused by the electrostatic interaction of very fine volcanic “ash” particles in the air. Weather satellites and lightning researchers are calling this one of the most significant events they have ever seen, with lightning strikes peaking at 63,000 events per 15 minutes.

Past eruptions from this volcano – such as the 2014 eruption that created a new island – included many phases of eruption, and thus we could see more explosions in the coming days and weeks. One moderating factor is the caldera is now underwater, making it harder for eruptions to break through into the atmosphere.

This could mean a shift to more submarine-style explosive eruptions. While this would mean a smaller atmospheric impact, there could still be an elevated risk of tsunamis, and people who live in coastal areas around the Pacific should be on high alert in the coming weeks.

Even though our past research has highlighted the importance of the power of eruptions at this volcano, predicting volcanic eruptions to the day and hour remains impossible. This is particularly difficult at a volcano so far offshore, with no power and a shifting, dynamic environment. The only observations are possible via satellite methods, which give a few minutes warning at best for the local residents of Tonga.

They say every major eruption brings with it a new surprise. This event has shown us clearly volcanoes can be very effective at generating tsunami events, and while Tonga is a long way away from most other countries, its volcanoes can threaten low-lying areas of nations around the globe.

Over the next days to weeks, we will learn more about this fascinating and dangerous volcano and also the hazards of submarine calderas. Early reports suggest Tonga has experienced significant damage due to tsunami, with many outlying areas still out of reach. We can only hope at the moment everyone in Tonga is safe and well.