It’s been nearly two years since China shut its international borders as part of its efforts to keep Covid-19 out.

China tamed the initial outbreak in Wuhan by locking down the city of more than 10 million people, confining residents to their homes for weeks and suspending public transportation.

Since then, Beijing has adopted a zero-tolerance playbook to quell resurgences of the virus. Harnessing the reach and force of the authoritarian state and its surveillance power, it has imposed snap lockdowns, tracked close contacts, placed thousands into quarantine and tested millions.

Before anywhere else in the world, China’s economy roared back to growth and life returned to something approaching normal — all within a bubble created to shield its 1.4 billion people from a raging pandemic that has wreaked havoc and claimed millions of lives across the globe.

The ruling Communist Party has seized on that success, touting it as evidence of the supposed superiority of its one-party system over Western democracies, especially the United States.

But as the pandemic drags on, local outbreaks have continued to flare up, frustrating the government’s mission to eliminate the virus within China’s borders.

And now, as much of the world starts to reopen and learn to live with Covid, China is looking increasingly isolated by comparison — and determinedly inward-facing.

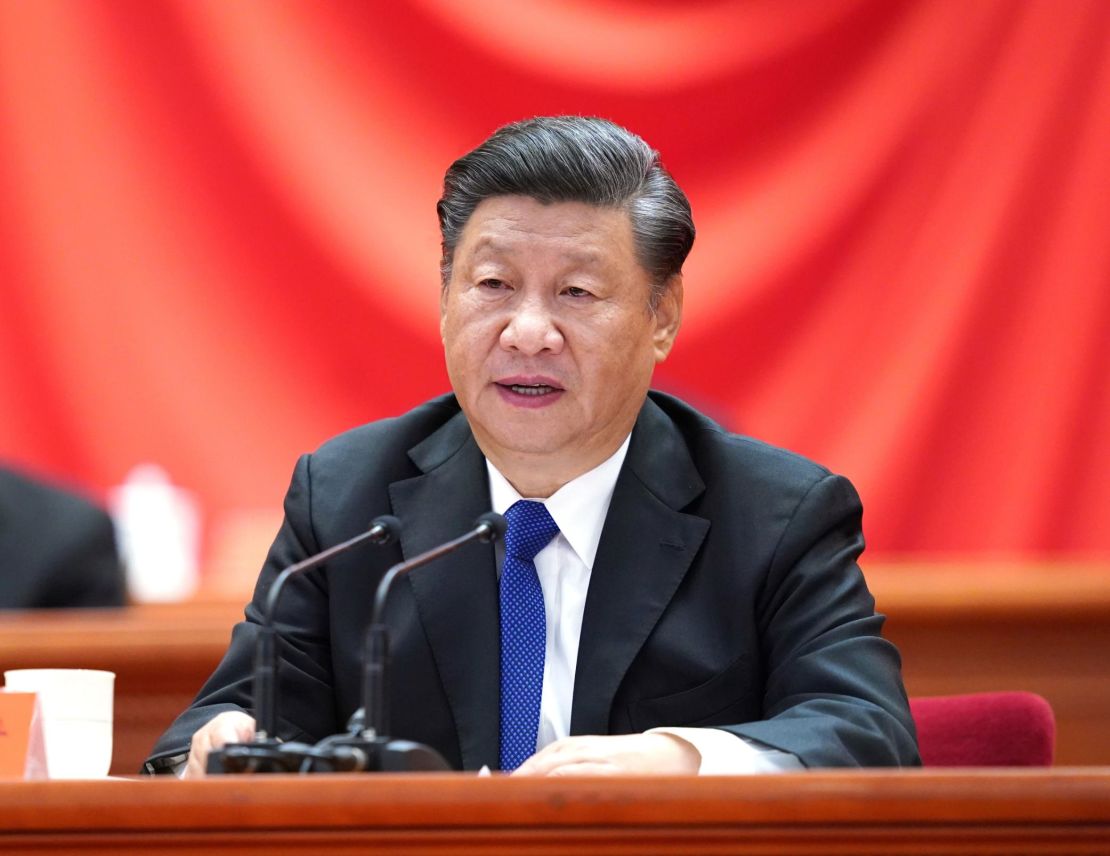

This apparent inward turn is evident in the itinerary of the country’s supreme leader Xi Jinping, who hasn’t left China for almost 22 months and counting.

It is manifest in the drastic reduction in people-to-people exchanges between China and the rest of the world, as the flow of tourist, academic and business trips slows to a trickle.

But it is also reflected in parts of the country’s national psyche — a broader shift that has been years in the making since Xi took the helm of the Communist Party nearly a decade ago, yet accentuated and exacerbated by the pandemic and the politics around it.

While taking increasing pride in China’s traditional culture and growing national strength, many Chinese people are turning progressively suspicious, critical or even outright hostile toward the West — along with any ideas, values or other forms of influence associated with it.

In a sense, the closed borders have almost become a physical extension of that insular-leaning mentality taking hold in parts of China, from top leaders to swathes of the general public.

For now, Beijing’s zero-Covid policy still enjoys overwhelming public support, even as China shows no sign of reopening in the foreseeable future. But analysts question how sustainable it is for the country to remain shut off from the world — and whether there could be considerations other than public health at play.

Sealed behind China’s borders

For nearly two years, most people in China have been unable to travel overseas, due to the country’s stringent border restrictions: international flights are limited, quarantine upon reentry is harsh and lengthy, and Chinese authorities have ceased issuing or renewing passports for all but essential travel.

Foreign visitors, from tourists to students, are largely banned from China. Those few who are allowed to enter, as well as returning Chinese citizens, must undergo at least 14 days of strict centralized quarantine. And that can be extended to up to 28 days by local authorities, often followed by another lengthy period of home observation.

The Chinese government has ordered local authorities to build permanent quarantine facilities for overseas arrivals, following the example of the southern metropolis of Guangzhou, which erected a 5,000-room quarantine center spanning an area the size of 46 football fields.

With the borders virtually sealed, even China’s top leaders are bunkering down in the country. Neither Xi nor Premier Li Keqiang, or the other five members on the party’s top decision-making Politburo Standing Committee, are known to have made foreign visits during the pandemic.

Xi’s last trip abroad was in January 2020, when he made a two-day visit to Myanmar to promote his signature Belt and Road Initiative — an ambitious program to boost infrastructure and trade across Asia, Europe and Africa, which has lost much of its steam since Covid-19 emerged.

The border closure has also come as China is turning inward on itself ideologically under Xi, said Carl Minzner, a senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Ideologically, China is slowly becoming more insular compared to the reform and opening up era of the ’80s and ‘90s — this is a hallmark of Xi’s new era,” he said.

Over the past years, a revival of traditional culture has taken hold across Chinese society, particularly among the younger generation who are proud of their cultural roots.

The trend is encouraged and heavily promoted by the party, in what Minzner calls “a strategic effort to deploy Chinese tradition as an ideological shield against foreign values, particularly Western ones.”

Since taking office in late 2012, Xi has repeatedly warned against the “infiltration” of Western values such as democracy, press freedom and judicial independence. He has clamped down on foreign NGOs, churches, as well as Western textbooks — all seen as vehicles for undue foreign influence.

That has fueled a growing strand of narrow-minded nationalism, which casts suspicion on any foreign ties and views feminism, the LGBTQ movement, and even environmentalism as stooges of Western influence designed to undermine China.

Since the pandemic, that intolerance has only grown.

In June, nearly 200 Chinese intellectuals who participated in a Japanese government-sponsored exchange program were attacked on Chinese social media and branded “traitors” — for trips they took years ago.

In July, journalists from several foreign media outlets covering deadly floods in northern China were harassed online and at the scene by local residents, with staff from the BBC and Los Angeles Times receiving death threats, according to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China.

And in August, a Chinese infectious disease expert was called a “traitor” who “blindly worshiped Western ideas” for suggesting China should eventually learn to coexist with Covid. Some even accused him of colluding with foreign forces to sabotage China’s pandemic response.

While it is unclear to what extent these nationalist sentiments represent mainstream opinion, they’ve been given overriding prominence in China’s government-managedpublic discourse, where most liberal-leaning voices have been silenced.

Victor Shih, a China expert at the University of California, San Diego, said while Xi’s predecessors had “grudgingly tolerated” Western reporters, NGO workers and sometimes even welcomed academics to China, the current administration now views their presence as sources of undesirable influences.

And Covid measures have become a convenient way to keep them out. Since the pandemic, most academics and non-profit workers have stopped going to China due to the border restrictions and quarantine requirements, Shih said.

“This heavy filter that is applied today — and had been applied prior to the pandemic — will help filter out what (Chinese leaders) see as undesirable elements from coming into China and polluting the values of the Chinese people,” Shih said.

But even after the border reopens, it remains to be seen how the Chinese government will allow foreign visitors to return — and whether some sort of additional screening might stay in place.

“The question is how quickly it’ll want to relax restrictions on the flows of people into and out of China. Currently, that’s primarily a health-related issue. But I do think the longer it takes, it also begins to get fused into political issues,” said Minzer, from the Council on Foreign Relations.

“It totally seems possible to me that the relaxations happen for different groups at different times,” he said, adding that foreign researchers who focus on topics the Chinese government deems politically sensitive could be among the last to be allowed in.

But Shih noted that attempts to eliminate “foreign influence” were unlikely to work, when China eventually resumes contact with the world.

Despite Beijing’s deteriorating relations with the United States, Britain, Australia and other Western countries, large numbers of Chinese students are still likely to pursue their studies there.

When the US Embassy and consulates in China resumed issuing student visas to Chinese nationals in May, they were flooded with applications. In August, before the start of the new academic year, the Shanghai Pudong International Airport saw long lines of students and parents with big suitcases stretching hundreds of meters at check-in.

“China cannot do without its best and brightest. They will go back to China — having lived in the West, some of them will love China even more, others will gain this skepticism about the Chinese political system,” he said.

Public support for zero Covid

For now, Chinese authorities are doubling down on their resolve to eliminate the virus, resorting to increasingly extreme measures to curb local flare-ups.

Public health experts have attributed China’s reluctance to relax its zero-Covid policy partly to uncertainty about the efficacy of Chinese vaccines, especially in face of the highly infectious Delta variant.

But political considerations have also played a role. Since containing the initial outbreak in Wuhan, the Chinese government has held up its effective containment efforts as proof of the supposed superiority of the country’s authoritarian political system. The success of zero-Covid is thus hailed as an ideological and moral victory over the faltering response of the US and other Western democracies.

And there is plenty of public support for the hardline approach, too. In China, public tolerance toward infections is extremely low, and fear of the virus still runs high – partly caused by scarring memories of the devastation in Wuhan, but also fed by unrelenting state media coverage on the horror of rampaging infections abroad.

Beijing has repeatedly blamed local flare-ups on the import of coronavirus from overseas, either through air passengers, frozen food or other goods. On social media, calls have been growing for authorities to extend the already lengthy quarantine for overseas arrivals, as many blamed Chinese travelers returning from abroad for bringing the virus to China.

“In mainstream opinion, Covid-19 is still regarded as an extremely deadly disease – even if you don’t die from it you’ll suffer from some kinds of serious health problems for the rest of your life – people are genuinely afraid,” said Lucas Li, a software engineer from southern Guangdong province.

Li, who works in California, has had a tough time traveling between China and the US over the past two years. After returning home for Lunar New Year in 2020, he was trapped for eight months in China due to the US travel ban. Then in May, he had to rush home again for family reasons, but flights to China were hard to come by. He ended up paying $4,800 for a one-way ticket – about seven times the price of a round trip in usual times – and underwent two weeks of hotel quarantine.

Li said while he doesn’t necessarily agree with zero-Covid, he understands why the government is sticking to it. The border closure has had limited impact on the Chinese economy, and the lack of international travel or exchanges is hardly a concern for most people, he said.

While overseas vacations had become a common part of life for China’s growing middle class, the country’s vast size and rich diversity provides plenty of options for domestic tourism as an alternative. And for people like Li, essential travel outside of China is still possible, albeit troublesome.

“I’m very sure the mainstream public opinion will choose to continue with the border closure – this is without a doubt,” Li said.

But experts say that could come at a political cost for China, which has seen its international image plummet since the start of the pandemic. Unfavorable views of China have reached record highs among much of the developed world, according to surveys conducted by the Pew Research Service.

“Other political parties, or even maybe Xi’s predecessors, might have seen this dramatic reduction in contact between China and the rest of the world as a big problem. But for now, the Xi administration does not seem to recognize this as a problem,” University of California’s Shih said.

“(If) China wants to persuade the world that it is a benign power … it needs to engage the world.”

But right now, that seems a long way off.