There’s a scene in Rebecca Hall’s film “Passing” in which the character Irene Redfield vents to her husband about a childhood friend.

The friend is Clare Kendry, a light-skinned Black woman who for years has been living as White. Since the two reconnected during a chance encounter in Chicago, Clare has been writing to Irene in hopes of meeting again and fulfilling a desire to be among Black people once more. Irene, who is also fair-skinned but lives a firmly Black middle class life in Harlem, is irritated that Clare wants it both ways – having acquired the privileges of Whiteness, she now longs for the community of Blackness.

“You’d think they’d be satisfied being White,” Irene remarks to her husband, seemingly referring to Clare and other Black people living as White.

He replies, “Who’s satisfied being anything?”

The exchange in the film, now on Netflix and based on Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel of the same name, alludes to many of the questions that drive narratives about racial passing – questions about the fluidity, incoherence and performance of identity, and what they can tell us about ourselves and society.

The term “passing” has historically referred to mixed-race Americans without visible African ancestry who posed as White to escape oppression or to gain access to social and economic benefits. Since the 19th century, writers both Black and White have explored the phenomenon through their work – Hall’s film adaptation of “Passing” is the latest such project in a long canon of stories on the topic.

For Hall, the subject of passing is personal – her maternal grandfather was an African American man who passed as White for much of his life. Larsen’s novel, and the process of adapting it for the screen, helped her make sense of her family’s complicated history, she said.

“The act of passing calls into question the stuff we talk about when we say race is a social construct and what that means,” the English writer-director told CNN. “But underneath that construct, it also points out how powerful it is and how real and human it is to long to be part of a category, even if it is limiting.”

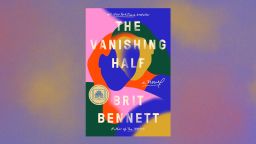

From James Weldon Johnson’s 1912 book “The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man” to Fannie Hurst’s 1933 “Imitation of Life” to Brit Bennett’s 2020 bestselling novel “The Vanishing Half,” stories about racial passing have captivated us for generations. Though instances of passing don’t appear to be as common today, our interest in the phenomenon endures.

Stories about passing have a long history

The first stories about passing in African American literature are about people who fled enslavement, said Alisha Gaines, an associate professor of English at Florida State University.

Gaines, the author of “Black for a Day: White Fantasies of Race and Empathy,” cited William and Ellen Craft’s “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom” as an early example of a passing narrative. In the 1860 book chronicling the couple’s escape from slavery, Ellen passed as a White male cotton planter while William posed as her servant.

In 1892, the abolitionist Frances E. W. Harper published the novel “Iola Leroy,” a story about the daughter of a White enslaver who upon her father’s death, learns that she has African ancestry and is subsequently sold into slavery. When she is eventually freed, she embraces her Black identity and dedicates herself to bettering the circumstances of her people.

While early narratives depicted passing as a means of survival, the stakes started to change in the early 20th century as shown through works like Larsen’s “Passing.”

By that time, Gaines said, passing had become a vehicle through which to obtain privilege and security. Authors writing about passing began considering murkier questions – what it meant to be loyal to one’s race, what was the value of Whiteness and what was lost when a person decided to pass. And it wasn’t just Black authors taking on the subject. White writers wrote about passing, too – notably, Fannie Hurst whose 1933 novel “Imitation of Life” was adapted twice for film.

Many of these early passing narratives followed a familiar storyline. Deploying a trope known as the “tragic mulatto,” a Black character (usually a woman) would opt to pass for White – only to find themselves unhappy in their new life. Caught between two worlds, the character would ultimately meet a tragic fate – a punishment of sorts for their deception.

But as time went on, contemporary authors put their own stamp on passing stories, defying the conventions of the genre and flipping tired narratives on their head, from Danzy Senna’s “Caucasia” in 1998 to Brit Bennett’s 2020 bestselling novel and soon-to-be TV series “The Vanishing Half.”

“Why we can trace them throughout time is because the questions around who is fit to be a citizen are underlying all of them,” Gaines said. “Who gets to live the alleged American Dream?”

They point to the messiness of race

Part of our fascination with passing stories stems from the pivotal role that race has played in the US since its founding, said Yaba Blay, a scholar and author of “One Drop: Shifting the Lens on Race.”

“Our society – in much of the way that it has been structured historically and contemporarily – is very much built and founded and grounded and structured on the notions of race as an important determinant of one’s identity because it’s also a determinant of one’s position in society,” said Blay.

But for all our fixation on race, our society lacks a clear understanding of what race actually is, she added. The US has historically operated under a Black and White framework of race, as though a person’s racial identity could be determined simply by assessing the color of their skin. As the rape of enslaved women at the hands of their enslavers threatened to muddle the nation’s racial hierarchy, the “one drop rule” emerged as an answer – meaning that a mixed-race person with known African ancestry was to be considered Black.

“Passing” – and stories about passing – destabilize those rigid categories of race and highlight their inherent contradictions, Blay said. If a person who is ostensibly Black according to the prescribed definitions is able to cross the so-called color line and pass themselves off as White, it calls into question the entire concept of race.

“If there’s power and privilege isolated in Whiteness and you have the potential to possibly get it, then what is race?” Blay said. “What is a racial identity?”

That idea of race as both fictional and real is what Brit Bennett wanted to explore when she set out to write “The Vanishing Half.” The novel focuses on two identical twin sisters, Desiree and Stella, whose paths diverge dramatically: Desiree marries a dark-skinned Black man and gives birth to a similarly dark-skinned daughter, while Stella leaves behind her family to pass for White. The choices they make end up shaping the trajectories of their lives and of their children’s.

“I kept coming back to the inherent absurdity of the idea that race can be successfully performed, but at the same time, the implications of race and of racism are felt generations deep,” Bennett told CNN. “They follow people from the cradle to the grave.”

“The Vanishing Half” and other passing stories resonate because they challenge the ways we think about identity, Bennett said. They push against our instincts to swiftly categorize people and force us to sit with the discomfort of those categories being blurrier than we imagined. That the character of Stella is able to transform into a White woman just because people assume so – and that she would choose to go along with it – is a reality that’s difficult to comprehend.

“There is something about that that becomes fascinating to readers and to audiences – to see characters that are challenging those categories that we take as given, to see characters push back at these labels that we assign very quickly and easily when we encounter people in the world,” she added.

Conversations about race in the US have evolved since the era of the “one-drop rule,” said Gaines. Institutions and forms now allow us to identify in more detailed ways, and an increasing number of people are claiming multiracial identities. Waves of immigrants from non-European countries have contributed to a more complex understanding, too.

“We’re starting to have more complicated conversations where we realize that the binary is not just Black and White,” Gaines said. “But we’re still a work in progress.”

The pressure for people to “choose a side,” however, hasn’t faded, she added – meaning the questions explored in stories about passing remain relevant as ever.

They allow us to imagine other possibilities

In a nation so consumed with identity politics, it’s perhaps no surprise that stories that challenge the very concept of those identities would resonate.

Allyson Hobbs, an associate professor of history at Stanford University and the author of “A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life,” said we’re drawn to stories about passing because so often, society dictates who we are and who we should be.

“There’s something about American society that’s been very invested in maintaining, enforcing, legalizing these racial categories or gender categories or sexual orientation categories or categories dealing with citizenship status that don’t actually represent the ways that people actually experience and live their lives,” she said.

Through characters who manipulate those identities for their own ends, we can imagine other possibilities in which we reject those labels and take control of our own destinies, Hobbs said. These narratives also resonate because of the various ways in which people have sought to escape the confines of their identities throughout history, she said – from Jewish people changing their names to get into colleges to women disguising themselves as men to live the lives they wanted.

At the heart of passing stories are universal questions of identity: How we make sense of ourselves and how we create our own realities. Those questions continue to permeate our society.

“Passing is really much more universal than we think of it as being,” Hobbs said. “We often think about it as a Black person passing as White, and we don’t really realize that in fact, all of us pass in some way at some time.”

It’s a thought also voiced by the character Irene in “Passing,” when a White man she’s friends with asks her why she too hasn’t chosen to pass.

“We’re all of us passing for something or other,” she muses during the film. “Aren’t we?”