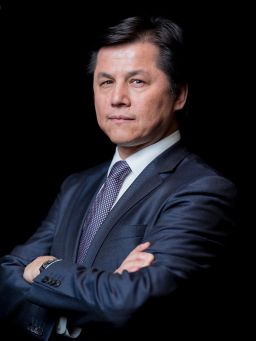

Editor’s Note: Nury Turkel is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute, vice chair at the US Commission on International Religious Freedom and fellow of the Renew Democracy Initiative’s Frontlines of Freedom project. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

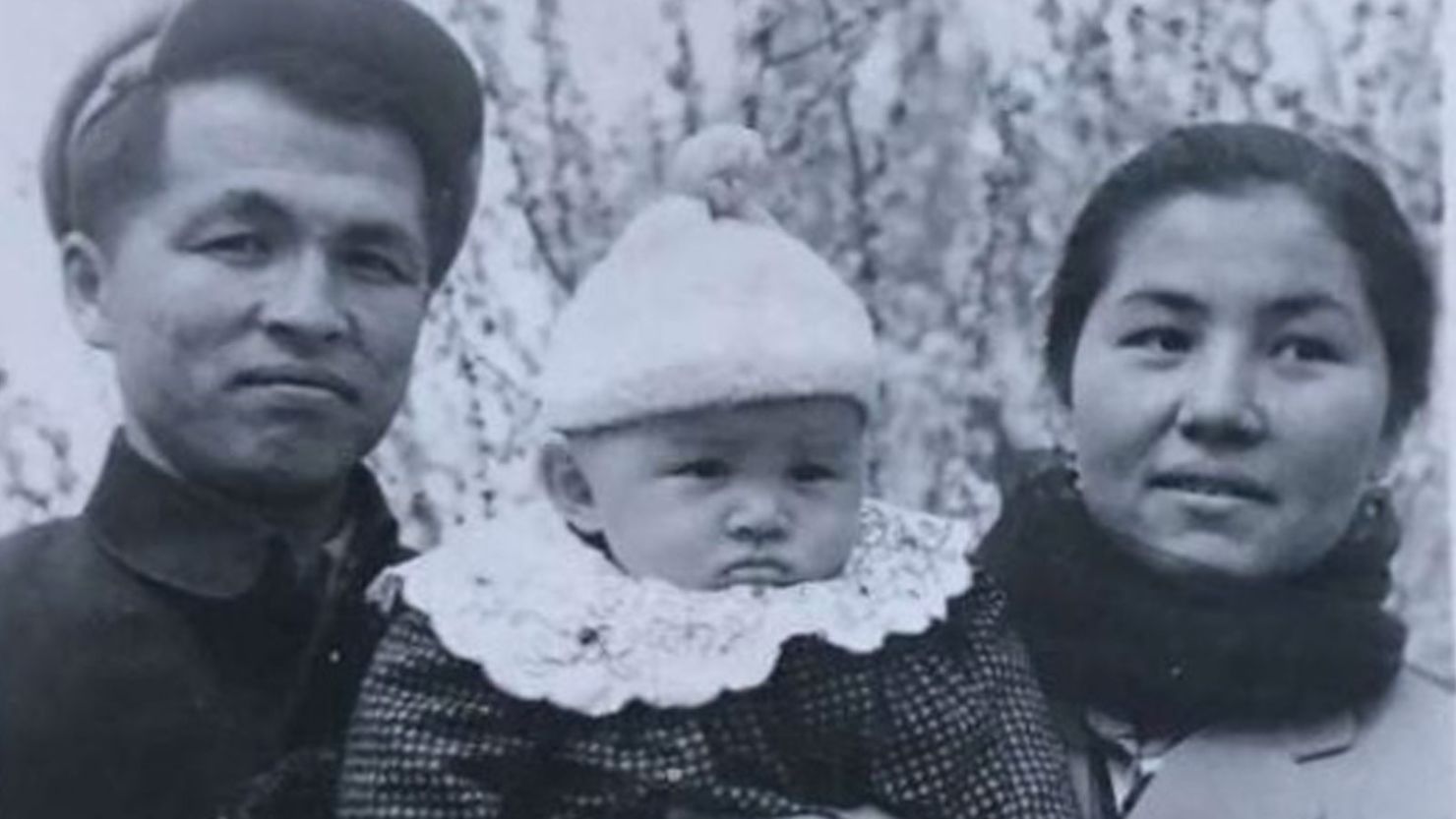

I was born in a Chinese reeducation camp, where my mother was detained in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which many Uyghurs call East Turkistan. For most of my life, I tried to forget the horrific experiences my mother and I had during my early childhood. But it seems the past is repeating itself – and with a vengeance.

When I was born, the Uyghur region – like the rest of China – was in the throes of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. It was a period of totalitarian zeal: Almost anyone suspected of not being adequately communist was beaten, jailed or killed. Religious and ethnic minorities were particular targets.

Mao’s zealots, called the Red Guards, came to the traditional Uyghur homeland to enforce the brutal policies of the tyrannical regime. The Red Guards burned religious texts, destroyed mosques, banned Uyghur-language books and ordered millions of Uyghurs – including my mother – into reeducation camps to be indoctrinated in Maoist doctrines and to be “reformed” through hard labor.

While arbitrary reeducation on a large scale experienced a lull following the end of the Cultural Revolution, forced labor programs have remained a human rights concern in China in spite of the economic reforms of the following decades.

Now, some half a century later, China is targeting the Uyghur population with a new fervor. According to the US Department of Defense, China has detained possibly as many as 3 million Uyghurs in detention camps. Meanwhile, based on satellite imagery, CNN reports China has been destroying traditional Uyghur cemeteries. And, according to the accounts of several Uyghur women, it is incorporating an extensive forced sterilization program.

Having experienced the reality of living under this regime, and now watching with horror as these atrocities are visited on my Uyghur brothers and sisters, it’s difficult for me to comprehend how any Western actor could push for greater dialogue or engagement with such a regime.

How cheap are the lives of my people to the international community if it ignores reports of the Chinese government’s attempt to commit genocide against the Uyghurs? Democracies and nongovernmental organizations alike must do significantly more to support the Uyghur struggle – even if it comes with an inevitable backlash from the Chinese government.

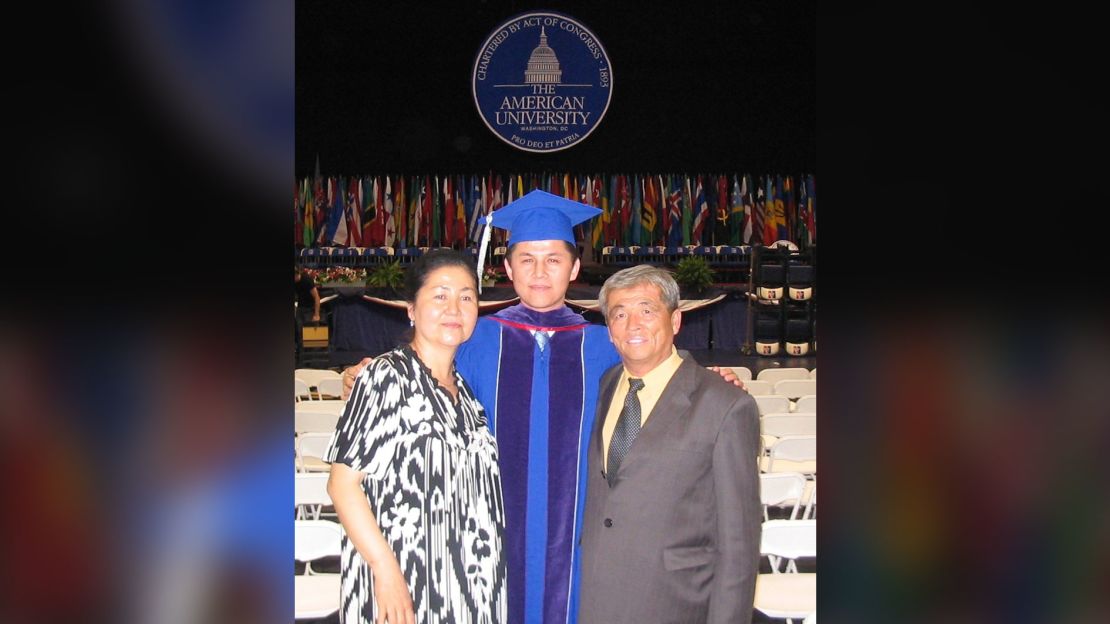

Since leaving China in 1995 to seek political freedom and pursue graduate education, I have made it my mission to speak out against the horrors perpetrated against the Uyghurs, despite the serious consequences I have had to pay. I have not seen my mother or father for more than 17 years. The Chinese authorities have prevented my ailing and aging parents from leaving to reunite with their American children and grandchildren. Though my parents have never been given a clear reason for this, I strongly believe it is because of my criticism of the Chinese government.

As a lawyer, human rights advocate, and now vice chair for the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), I have advocated for human rights and religious freedom in China and around the world for many years. And, in these capacities, I have seen real progress in raising awareness of the atrocities perpetrated in the Uyghur region. But to have any meaningful impact, the world’s leading democracies must pursue a bolder strategy aimed squarely at hitting China where it hurts – weaponizing import bans and strategic investments.

Appallingly, many of the products enjoyed by Western countries are made by interned Uyghurs in China. According to several reports, Uyghur forced labor contributes significantly to the world economy – particularly solar-panel manufacturing and cotton-growing industries. In a liberal international order, there can be no room for forced labor.

The US Senate has taken serious steps forward on this issue by passing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which establishes broad import bans on products from the Uyghur region. The US House of Representatives, which passed an earlier version of the bill in 2020, must now move quickly to pass this bill, so that President Joe Biden can sign it into law.

Our European partners – another enormous market for Chinese products – must follow suit, and the United States should encourage our allies to join us in rooting out this evil practice. While the European Union is currently crafting due diligence protocol to address human rights violations within EU supply chains, it has not given a strong enough indication that it will adopt broad import bans for products produced by Uyghur forced labor.

Europe endured the worst of the horrors of Nazism, fascism and communism – and should understand the consequences of failing to act in the face of a regime that seeks to eradicate minority groups. If the EU is to have any credibility as a moral leader, it must ban the import of products from Xinjiang.

Indeed, such bans, which go further than many of the existing sanctions already in place, can go a long way toward mitigating the atrocious crimes that Beijing is committing in the Uyghur homeland. Consider some of the US sanctions, which are already proving to be effective at chipping away at two things the Chinese party leadership cares most about – economic interests and public image.

Banning the import of agricultural products – such as cotton and tomatoes – has fractured the supply chains for the fashion and food industries. And the enforcement measures behind these sanctions have also created pressure points for US companies, forcing them to recognize the risks of doing business in China while also facing administrative, legal and reputational risks in the United States. In addition, public naming and shaming through the use of sanctions has sent a powerful message to Beijing that perpetrators of human rights abuses cannot remain anonymous.

That’s not to say that this is a risk-free proposition for the countries implementing such a ban. Italy is one of the leading global importers of goods from Xinjiang, and it may be challenging for such a country to cut itself off from Xinjiang products, even if it would like to. That’s why it’s critical for powerful economies like the United States and other democracies to invest in viable alternatives to China’s forced-labor products, thereby making it easier for countries to diversify their supply chains.

This June, the US Senate passed the US Innovation and Competition Act, which designates $250 billion to boost American scientific research, design and semiconductor manufacturing. The United States and its democratic partners should consider similar legislation to boost the manufacturing of products that have until now been dominated by companies operating with forced labor in Xinjiang.

Both Donald Trump’s and Joe Biden’s administrations have labeled China’s actions toward the Uyghurs as a genocide, and the Canadian, British, Dutch and Lithuanian Parliaments have concurred. State signatories to the United Nations Genocide Convention are obliged to take action to halt genocide when it occurs and punish the perpetrators. Yet so much more remains to be done to address the continuing horrors of Xinjiang.

This cuts to the legal and moral core of the liberal international order. The dual strategy of import bans and domestic investment may not be a panacea, but it is undoubtedly a meaningful step in the right direction. After watching a lifetime of abuse by the Chinese regime, such actions give me at least a glimmer of hope that Uyghur lives mean more to the international community than platitudes.

Editor’s Note: The Chinese government has repeatedly denied any allegations of crimes – including forced labor and forced sterilization – against the Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples. It claims it is providing the Uyghurs with education at “vocational training centers” while assisting in deradicalization efforts to combat alleged terrorism.