Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

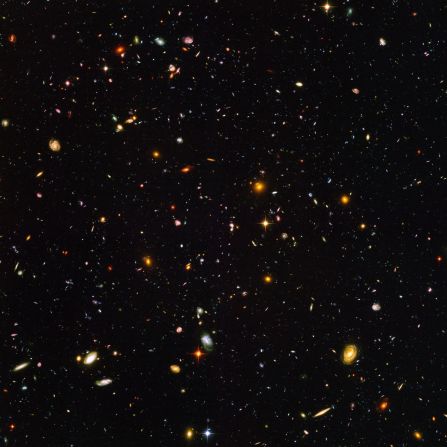

Astronomers had an unprecedented front-row seat to the explosive death of a star 60 million light-years away. They witnessed the event thanks to telescopes on the ground and in space, including the Hubble Space Telescope.

These observations not only provided groundbreaking insight into what happens before a star dies, but could also help astronomers develop an early warning system for stars that are about to meet their end.

“We used to talk about supernova work like we were crime scene investigators, where we would show up after the fact and try to figure out what happened to that star,” said Ryan Foley, leader of the discovery team and assistant professor in the University of California, Santa Cruz, astronomy and astrophysics department, in a statement.”This is a different situation, because we really know what’s going on and we actually see the death in real time.”

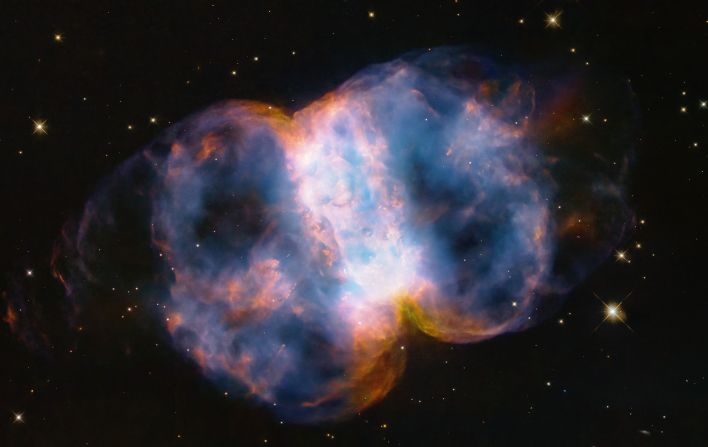

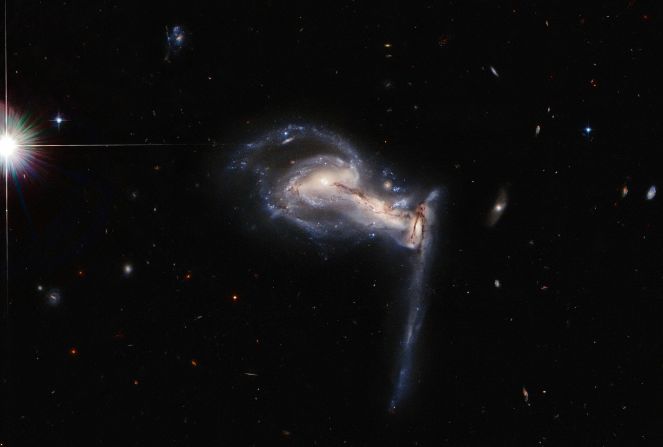

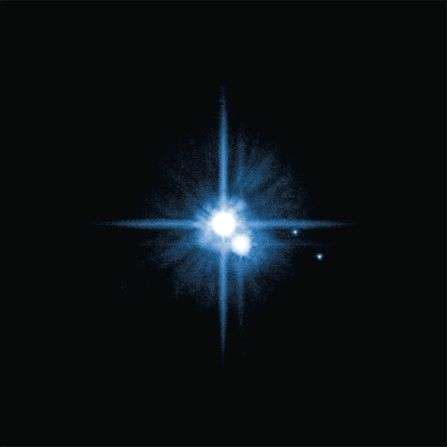

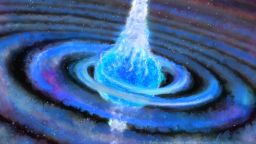

The supernova, called SN 2020fqv, is located in the interacting Butterfly Galaxies, which can be found in the Virgo constellation. While the star’s deathoccurred millions of years ago, the light from the supernova is just now reaching Earth.

The supernova was discovered in April 2020 by astronomers using the Zwicky Transient Facility at the Palomar Observatory at the California Institute of Technology in San Diego. The celestial event was also under observation by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS. Scientists mainly use TESS to search for planets outside of our solar system, butthe satellite also stares at the stars and has made other discoveries beyond finding exoplanets.

Pioneering observations before a star’s death

Following the breaking discovery,astronomers rapidly aimed Hubble, as well as ground-based telescopes, at the supernova. Together, the observations provided a complete overview of the first moments of the star’s death and what followed.

Hubble was able to spot circumstellar material around the star shortly after the explosion. The aging star releasedthis material in the final year before its death, allowing astronomers a glimpse into what happened prior to the supernova.

“We rarely get to examine this very close-in circumstellar material since it is only visible for a very short time, and we usually don’t start observing a supernova until at least a few days after the explosion,” said lead study author Samaporn Tinyanont, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in a statement. “For this supernova, we were able to make ultra-rapid observations with Hubble, giving unprecedented coverage of the region right next to the star that exploded.”

A study detailing these findings will soon be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Invaluable data may help find other supernovas

To understand more about the history of the star, the research team used previous Hubble observations of the astronomical object over the last few decades. And TESS had captured an image of the star every 30 minutes for several days before the supernova occurred, as well as during the event and for several weeks afterward.

What emerged was a portrait of the star’s life across multiple decades before it died in a spectacular explosion.

“Now we have this whole story about what’s happening to the star in the years before it died, through the time of death, and then the aftermath of that,” Foley said. “This is really the most detailed view of stars like this in their last moments and how they explode.”

The researchers refer to the event as “the Rosetta Stone of supernovas.” Much like the three languages included on the famed ancient stone tablet, three methods helped the research team discover more about the star.

Archival Hubble data, theoretical models and observations of the supernova helped the team determine the star’s mass, about 14 to 15 times the mass of the sun, before it exploded. In order to understand how massive stars die, it’s imperative to understand their mass.

“People use the term ‘Rosetta Stone’ a lot. But this is the first time we’ve been able to verify the mass with these three different methods for one supernova, and all of them are consistent,” Tinyanont said. “Now we can push forward using these different methods and combining them, because there are a lot of other supernovas where we have masses from one method but not another.”

Based on the pattern of behavior witnessed before this supernova, scientists may be able to apply their findings to find other stars on the brink of explosion. Before stars explode, they become more active and release material.

“This could be a warning system,” Foley said. “So if you see a star start to shake around a bit, start acting up, then maybe we should pay more attention and really try to understand what’s going on there before it explodes. As we find more and more of these supernovas with this sort of excellent data set, we’ll be able to understand better what’s happening in the last few years of a star’s life.”