Editor’s Note: Noah Berlatsky is the author of “Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.” The views expressed here are solely the author’s. View more opinion articles on CNN.

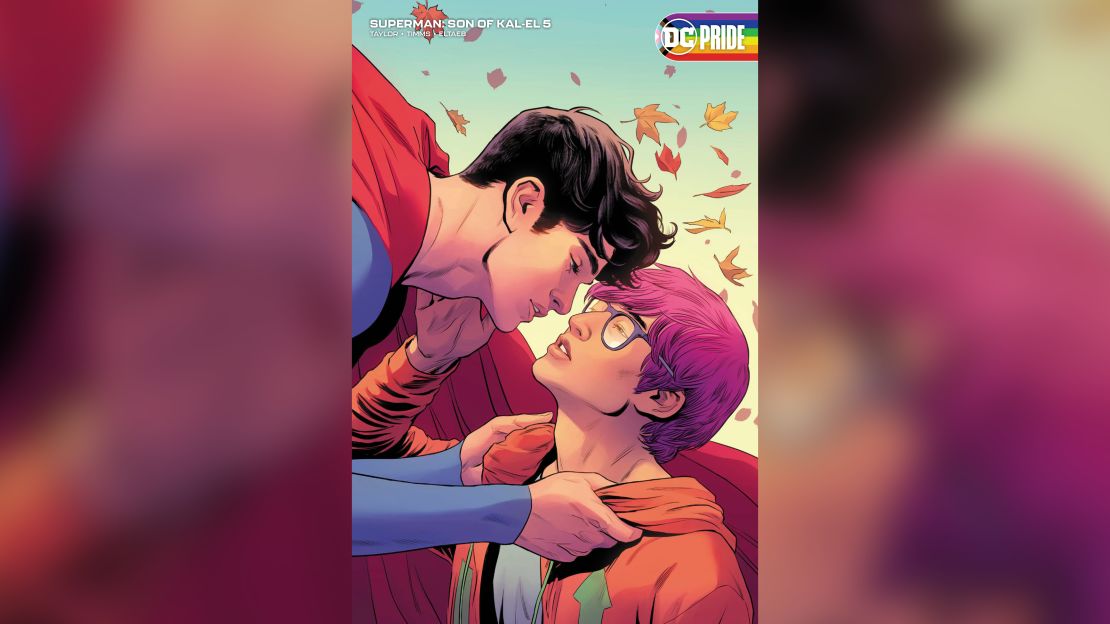

When Jonathan Kent, the new Superman, comes out as bisexual in next month’s issue of “Superman: Son of Kal-El,” he won’t be the first queer superhero. But he will be one of the most visible. As such, Jonathan defies stereotypes about sexuality and masculinity that have shaped the character and the superhero genre for generations.

In the new storyline – prompted by an aging Clark Kent passing the super-baton to his son – Superman shares a kiss with his friend and ally Jay Nakamura, a computer hacker and activist who admires Superman’s mom, journalist Lois Lane. A bisexual Superman is an important step for LGBTQ representation. It’s also a sign of how recognizing that there are options other than heterosexuality can change superhero preconceptions about goodness, masculinity and empowerment.

Superman has always been written as heterosexual. But the original 1930s-40s Superman comics by Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster can make you wonder. The comics feature a love triangle: Nerdy, bumbling reporter Clark Kent pursues Lois Lane; Lois Lane has no interest in him, and she instead pursues Superman – who has little interest in her.

Superman and Clark Kent are, of course, the same person. Clark is Superman’s secret identity – his closet. When he’s Clark, Superman pretends to be weak, fashion-backwards and besotted with Lois. Then he sheds his workaday clothes for the sleek cape and tights and completely ignores the woman who wants him.

This is a dynamic which led homophobic critic Fredric Wertham to suggest in the 1950s that superheroes (especially Batman and Robin) promoted homosexuality through their privileging of male/male bonds. It’s also perhaps contributed to stereotypes of comics readers as nerdy and unmanly.

The point here isn’t that Superman was really gay in those early comics. But the obsession with double identity and disavowed desire does suggest that the character has been built on anxieties about homosexuality and masculinity. Superman is portrayed as the ultimate man – and in many stories about him, being the ultimate man means being untainted by a feminizing interest in women. (In the 1980 film “Superman II,” he has to choose between his love for Lois and losing his powers.) But at the same time, refusing to date women also makes Superman less than fully male in a homophobic, misogynist culture which sees homosexuality as feminine and therefore lesser.

Trying to walk the tightrope between these rigid standards means that to be heterosexual, you need to be both interested in women and uninterested in women. That’s impossible. Superman’s idealized masculinity is unstable and paranoid, and therefore has to be constantly reinforced. The superhero genre does that by routing its emotional energy away from love and toward violence.

Superman’s most intense relationship through much of his career is not with Lois Lane, but with Lex Luthor or other antagonists (like Batman in the recent “Batman vs. Superman” film.) Good, clean male violence occupies the place in the stories that might otherwise be taken up by feminine-coded, and therefore suspicious, love.

There are superhero stories over the years, though, that have questioned the genre’s interlinked commitments to homosexual panic and to violence. William Marston’s “Wonder Woman” comics in the 1940s, for example, included lots of female/female spanking rituals and bondage imagery; its heroine, not coincidentally, was much more interested in reforming villains than in punching them.

Grant Morrison, a nonbinary creator, wrote “Doom Patrol” in the 1980s, a comic with a nonbinary character and a superteam that decided the villains were ideologically in the right as often as not. April Daniels’ wonderful recent “Dreadnought” novels feature a trans lesbian superhero who loves beating the tar out of bad guys – but slowly comes to realize that her violent approach to problem-solving is unhealthy for both herself and others.

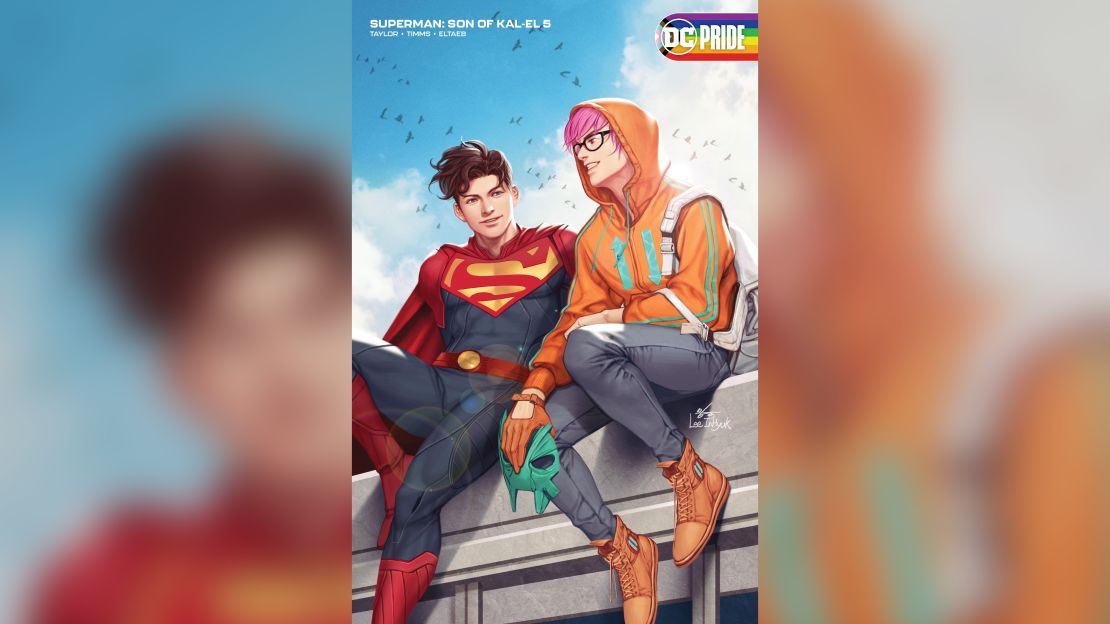

“Superman: Son of Kal-El” has also challenged its genre’s historical predilection to anxiously flee from romance to fisticuffs. Jon Kent, son of Clark and Lois Lane, is not just figuring out what kind of man he wants to be, but what kind of hero.

As writer Tom Taylor explains, “The question for Jon (and for our creative team) is, what should a new Superman fight for today? Can a 17-year-old Superman battle giant robots while ignoring the climate crisis? Of course not. Can someone with super sight and super hearing ignore injustices beyond his borders? Can he ignore the plight of asylum seekers?”

Obviously, you can have LGBTQ superheroes who just fly around and hit people, like Carol Danvers in the “Captain Marvel” film. (Carol isn’t quite allowed to come out, but come on.) You can also have heterosexual heroes in comics that question whether super-punches are the best way to solve problems – as in Robert Kirkman’s 1990s comic “Invincible.”

But Superman’s heterosexuality was linked to his limitations. Male empowerment fantasies were also fantasies about doing sexuality right, without staining masculinity or showing weakness. Superman, in many of his iterations, is most scared not of Kryptonite but of femininity, which has stereotypically been lumped together with homosexuality. His fear powers the genre’s violence. Jon Kent, in embracing queer possibilities and pursuing good by not always hitting that giant robot, shows himself more courageous than his predecessor.