Russian state-backed hackers are having greater success at breaching targets in the United States and elsewhere as they make government organizations the primary focus of their attacks, according to data that Microsoft released Thursday.

Government organizations accounted for more than half of the targets for Moscow-linked hacking groups for the year through June 2021, compared to just 3% the previous year, according to Microsoft. At the same time, the success rate of Russian intrusions into government and non-government targets has gone from 21% to 32% year over year, the technology giant said in a report focusing on state-backed and cybercriminal activity.

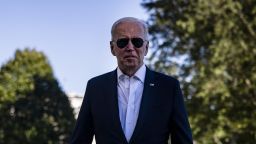

The report comes as the Biden administration has looked to bolster US government defenses against cyber espionage from Russia – and publicly expose that activity with US allies. The European Union last month blasted alleged Russian hacking and leaking operations that the bloc said were aimed at interfering in democracy.

But despite the US and its allies condemning Russian and Chinese behavior in cyberspace, those countries are “still comfortable leaning into nation-state attacks,” said Cristin Goodwin, associate general counsel and head of Microsoft’s Digital Security Unit. “And we’re seeing that increase.”

The data includes the Russian espionage operation that breached at least nine US federal agencies in 2020 by exploiting software made by SolarWinds, a Texas-based firm. CNN reported Wednesday that the same Russian group behind that activity has in recent months continued to try to breach US and European government organizations.

The Biden administration in April blamed Russia’s foreign intelligence service, the SVR, for that spying campaign. Moscow has denied involvement in the hacking.

North Korea, Iran and China were next most active countries

Microsoft also reported Thursday that 58% of government-linked hacking attempts originated in Russia, followed by 23% from North Korea, 11% from Iran and 8% from China.

The data comes with caveats. A flurry of unsuccessful attempts to guess target organizations’ passwords, for example, count as separate hacking attempts. And Microsoft did not report on US intelligence agencies, which also conduct cyber-espionage campaigns.

But with over one billion devices using Microsoft software worldwide, the technology provider has a broader view of malicious cyber activity than most other organizations. And the data tells its own story.

Cyber activity, for example, often correlates with larger geopolitical dynamics and tensions.

While Russia beefed up its troop presences along its border with Ukraine earlier this year, the same hacking group that carried out the SolarWinds breaches has “heavily target[ed] Ukrainian government interests,” according to Microsoft. The number of Microsoft customers in Ukraine “impacted” by the Russian hacking group soared to 1,200 in the fiscal year ending in June compared to just six the year prior.

“Historically, nation-state attacks tend to follow where a geopolitical priority sits for a country,” Goodwin told CNN.

Google on Thursday announced that APT28, a Russian hacking group that interfered in the 2016 election, had sent some 14,000 malicious emails to Gmail users around the world in late September. The phishing was aimed at government personnel, journalists and defense firms, among others, according to Google. US organizations were among those targeted.

Shane Huntley, director of the Google Threat Analysis Group, said that all of the emails had been classified as spam and blocked by Gmail.

Much of public attention on alleged Russian cyber operations in the last year has been on the group that bugged SolarWinds software. But there’s an array of hacking teams at Moscow’s disposal that carry out different missions against valuable targets in the US and allied countries, analysts say.

Some of those groups specialize in infiltrating critical infrastructure firms, both to collect information and, perhaps in some cases, to have a foothold into networks in the event of a conflict, according to some US officials and private sector experts.

Attacks on critical infrastructure

“The concern is that effort that we’ve seen [Russian groups] actively use disruptive effects around the globe,” Rob Joyce, head of the National Security Agency’s Cybersecurity Directorate, said at the Aspen Cyber Summit last week. “And we’ve seen evidence of prepositioning against US critical infrastructure. So, all things that can’t be tolerated and we need to work against.”

One such group, known as Berserk Bear in the cybersecurity industry, has been linked to breaches of industrial software at US electric utilities that the Department of Homeland Security blamed on Russian government hackers in 2018.

The group, which some analysts have linked to Russia’s FSB intelligence agency, has in the last three years shown a steady appetite for collecting data held by critical infrastructure firms in the US, Ukraine and Western Europe.

That includes breaches, in 2019 and 2020 respectively, of the websites of one Ukraine’s largest energy firms and San Francisco’s International Airport, according to Joe Slowik, a former cybersecurity specialist in the US Navy who now works at security firm Gigamon.

Over a decade of operations breaching critical infrastructure firms, Berserk Bear “has almost certainly facilitated significant intelligence gathering, capability development and potentially effects pre-positioning in highly sensitive networks,” Slowik said in a paper that will be presented at the Virus Bulletin conference this week.