A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Race Deconstructed newsletter. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up for free here.

October marks three decades since Anita Hill testified in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee that Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her when he was her boss at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

A Supreme Court nominee, the conservative Thomas was confirmed by a thin margin of 52-48. Hill was pilloried.

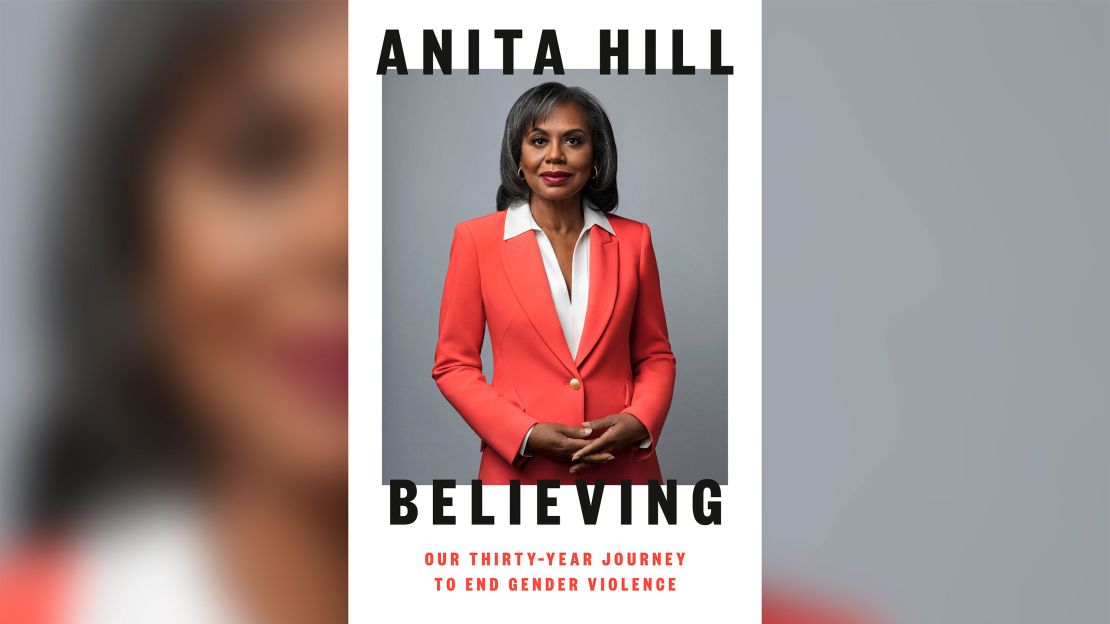

“I shared with only a few friends that Clarence Thomas’s behavior had been the main reason I’d left Washington and returned to Oklahoma,” she writes in her moving new book, “Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey to End Gender Violence.” “When I did tell, testifying at Thomas’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing, people of all races judged me. In hate mail sent to my office at the University of Oklahoma, on talk radio, in magazines and books, face-to-face, and over the phone, they confronted and condemned me.”

Since 1991, Hill has become a symbol: of the stakes of reporting harassment if you’re a woman, of the cruel ease with which people can look away from abuse. She’s also become a symbol of the way that lingering anger can be alchemized into action. The year after Hill’s testimony, a record number of women ran for Congress. And a record number won.

Hill isn’t merely a symbol, though. Rather than receding from view following her wrenching testimony before the all-White, all-male Senate Judiciary Committee, she charted a more activist course. Over the past 30 years, she’s embraced a role as an outspoken advocate for women’s rights and gender equality, especially for Black women.

Hill’s new book – her third – is by turns diaristic and scholarly, as the Brandeis University professor marshals elements of both memoir and academic analysis to underscore the urgency of rooting out gender-based violence. And she does all this with prose that’s at once sophisticated and blunt.

“When I first spoke publicly about my experience of being sexually harassed, at 35 years old, I was young and patient,” she writes. “Thirty years later, I make no claim to youth. And when it comes to ending violence and the inequality that it spawns, I am no longer patient.”

I recently talked with Hill about “Believing,” the variety of forces that protect men such as the R&B singer R. Kelly and ignore the claims of Black girls and women, and the deep sense of hope she finds in her mother’s legacy.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What has the social climate of the past several years – the high-profile police killings of Black Americans, the testimony that Christine Blasey Ford gave during Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing, the #MeToo Movement – revealed about the structural forces that affect racial and gender equality?

It’s revealed that these forces have been there – in some instances under the surface, and in other instances they surfaced but weren’t widely broadcast. In terms of race, we’ve seen over-policing incidents, incidents where Black men and women were killed by police or while in police custody. That’s the sort of racism that we’ve seen, that’s been a more obvious problem.

In terms of gender, we’ve learned over the past few years that rampant and egregious sexual misconduct – and that’s probably not even a strong enough term – has been occurring in various sectors. The #MeToo revelations pointed to behavior that was going on that was violent, that was typically directed at women but also at men. In the book, I talk about how to really get your mind around how pervasive the problem is, you have to look at the statistics and not at individual instances of misogyny and violence.

This week, R. Kelly received an overdue conviction. Some say that it took so long because of his superstardom; others say that it was because his victims were mostly Black girls and women, who, as you write in your book, face structural barriers and a culture that insists on writing off their claims as “not so bad.” What do you think?

I think that it’s a combination. For years nothing was done because he’s a very powerful individual in the music industry. I think that part of the dismissiveness in terms of attitudes toward his prosecution has been because they’re women of color who’ve been complaining. We know that when people look at who has credibility to talk about sexual misconduct, they look at it through an intense gender lens. And women of color are viewed through both a gender and a racial lens.

So, those two things intersecting or combining make it harder for Black women to be heard. This situation is associated with the whole concept of the perfect victim. And Black women are rarely viewed as the perfect victim. In fact, we know that there is no perfect victim. It’s a myth we create to excuse doing nothing about the problem.

How do we combat gender-based discrimination and violence in a way that also addresses race?

You have to do both. I don’t think that you can separate the two when you’re talking about the experiences of racial minorities who are also female or transgender or nonbinary or even male in some instances. You’ve got to take into account both elements. People have been talking about being anti-racist. You have to be not only anti-racist but also deliberately anti-sexist if you’re going to eliminate gender-based violence in the Black community.

At your core, you’re a very hopeful person. How do you keep that feeling?

Because I’ve seen change in my lifetime. But I don’t even look at my lifetime as a measure of change. My mother was born in 1911, and she died at 91 years old. What I like to think about – maybe it’s a way of not getting discouraged – is the change she was able to witness in her life, the change she was able to share with her children, who’ve had opportunities she never had. Especially her daughters, who were able to make some choices that were different from the choices she had.

She did farm work all her life. She had to leave school in the sixth grade. She had 13 children. She was happy as a mother and as a woman, but she came into a world that was very different from the world she left. I mark our progress by the change that occurred during her long life. So, I’ve seen the change. That’s why I’m hopeful that we can continue it – if we commit to it. Change happened in her lifetime because people committed to it.

The title of my book is “Believing.” That’s because I believe that change is possible, and I believe that we deserve more. I believe that women should expect to have more from our system than what we’re getting right now. So, the book is a conversation about our society’s journey, but it’s also about my journey, because I had to really grow to understand that the problem is bigger than me in 1991. It’s bigger than the issue of sexual harassment. It’s bigger than the hearings. I had to grow in terms of my understanding and knowledge of other experiences with sexual misconduct and gender violence.