Editor’s Note: Joshua Prager is a former senior writer for The Wall Street Journal and the author of “The Echoing Green” and, with Milton Glaser, “100 Years.” His newest book, from which this essay is adapted, is “The Family Roe: An American Story.” (W.W. Norton). The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Early this month, the Supreme Court chose to let stand Texas Senate Bill 8, a law that bans abortion after just six weeks of pregnancy and deputizes private citizens to enforce it. This new law is one of a number passed in recent years that flagrantly violate Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision which established a Constitutional right to abortion until viability – the point when a fetus can survive outside the womb.

Another such law in Mississippi, which bans most abortions after 15 weeks, will be before the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The Court, with its newfound 6-3 conservative majority, will hear the case in the coming term.

Roe’s constitutional protection of abortion is in genuine peril.

The last time it was in such danger was 1992, when the Supreme Court took up the case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, a Pennsylvania case focused on how and when a state may regulate abortion. At the time, abortion rights advocates feared the court would overturn Roe.

But as is well known, one of the junior justices on the Court, David Souter, secretly struck an alliance with Justices Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor to rescue Roe.

Less well known is the genesis of that rescue. Legal historians have long speculated about it, including David Garrow who, in 1994, wrote an article in the New York Times Magazine about Souter. It began: “No public document – and probably only a single very private one – marks April 23, 1992, as one of the more momentous days in recent Supreme Court history.” It was on that day, wrote Garrow, that Justice Souter decided how he would vote in Casey.

Garrow was right. There is a “very private” document that sheds light on Souter’s ruling: a memo written by one of his clerks that argued for precisely the compromise Casey struck between legal abortion and its regulation. The memo argued that the importance of legal precedent demanded that the Supreme Court not overturn Roe. The reputation of the Court as a neutral arbiter of law, wrote the clerk, depended upon it.

The memo is historic. Here, and in my book, it is quoted for the first time.

The origin of “Jane Roe”

Norma McCorvey was at a loss. The Dallas waitress no more desired to relinquish a third child to adoption than to become a mother. But in September 1969, she began to feel a familiar soreness in her breasts. Abortion remained illegal in Texas. And her doctor, Richard Lane, would not perform one.

Norma soon found an unlicensed doctor who would. But she could not afford his $500 fee. She was scared, besides, she later recounted, “to turn my body over to him.”

There was reason to think that the law might soon change; in the coming months, Alaska, Hawaii, New York and Washington would legalize abortion. Still, abortion was then only legal in Oregon and California, and not explicitly banned in Washington, DC. And while it was available to nonresidents in the latter two, Norma had no money to board a plane.

And so, in January of 1970, Norma reluctantly returned to Henry McCluskey, the Dallas lawyer who had found her second child a good home. He agreed to do the same for her third. But Norma said that what she really wanted was an abortion, and McCluskey told her that he knew a lawyer who wanted to challenge Texas’s abortion prohibition. Her name was Linda Coffee. She needed a plaintiff to bring her case.

Two months later, Coffee and her co-counsel Sarah Weddington filed suit on behalf of Norma, the anonymous plaintiff they renamed “Jane Roe.” Norma then gave birth in June to a baby girl McCluskey placed for adoption. The child was a toddler when, in January 1973, the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, granting women the right to an abortion “free of interference by the State.”

Nineteen years later, in 1992, that right was in jeopardy when the Supreme Court, and its presumed 5-4 conservative majority, readied to rule on Casey.

A historic memo, written for the ‘fifth vote to overturn Roe v. Wade’

David Souter was a deeply grounded person; the writer Janet Malcolm would note that he possessed a “moving absence of self-regard.” He had grown up in a farmhouse in the New Hampshire town of Weare, where he had returned to live after his schooling at Harvard and Oxford. He stayed in Weare until the Supreme Court took him from it, in October 1990, as an unmarried man of 51.

Resettled in the capital, Souter did his best to live without fuss, to jog, to eat his apples, core and all, to write longhand by natural light. Souter had spoken of Weare at his Senate confirmation hearing. But he’d said little of Roe, telling the Senate committee that it would be “inappropriate” for him to comment on it.

Pro-choice leaders were sure that the George H.W. Bush appointee was a foe. “I tremble for this country if you confirm David Souter,” warned Molly Yard, president of NOW, at his confirmation hearing. “He will be the fifth vote to overturn Roe v. Wade.”

To know the judge, however, was to know that he “thought and cared more deeply about the Constitution than he did about politics,” as Dahlia Lithwick wrote. It was also to know that his judicial hero was Justice John Marshall Harlan II, an Eisenhower appointee who believed deeply in the power of precedent.

Asked again and again about Roe – the ruling so dominated his hearings that one senator labeled them “a mockery of the process” - Souter wouldn’t say how he would rule on abortion. But he had made clear to the Senate committee his respect for what he termed “extremely significant issues of precedent.” That Roe had been law for a generation, he intimated, might be every bit as important as the question of its judicial rightness.

Souter knew that abortion was likely to return to the Court during his tenure. His first term on the Court was ending when, in June 1991, as former Harry Blackmun clerk Edward Lazarus later wrote in his book “Closed Chambers,” he asked his four outgoing clerks to write down their thoughts on the matter. Just one argued in favor of Roe, that clerk handing Souter 32 crystalline pages that centered on stare decisis – the doctrine that held, as Souter did, that legal precedents should ordinarily not be overruled. On the matter of abortion, wrote the clerk, that doctrine was particularly compelling. “Roe,” he wrote, “implicates uniquely powerful stare decisis concerns.”

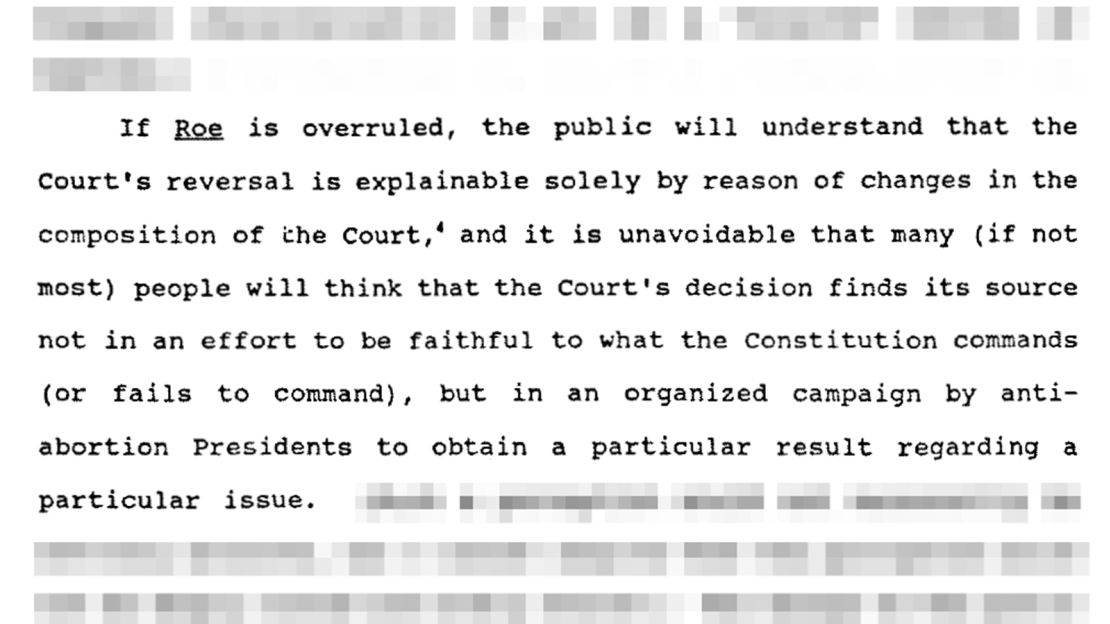

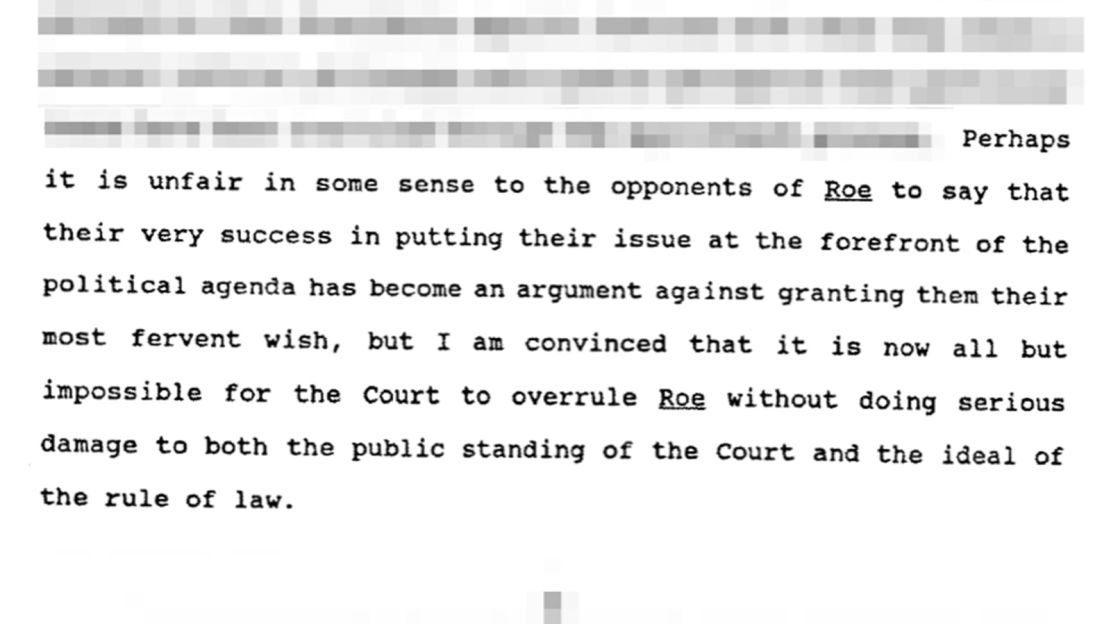

Prominent among those concerns, wrote the clerk, was that the influence of Roe on the selection of justices posed a particular danger. “If Roe is overruled,” he argued, “the public will understand that the Court’s reversal is explainable solely by reason of changes in the composition of the Court.” Thus, he concluded: “The damage to the public understanding of the Court’s decisions as neutral expositions of the law … would be incalculable.”

The memo added that all of the proposed legal rationales for overturning Roe would threaten Griswold v. Connecticut, the landmark 1965 decision recognizing a right to contraception that established the Constitutional basis for the right to privacy. And it was relevant to the goals of stare decisis, wrote the clerk, that a generation of women had acclimated to Roe, had “shaped their lives around that right.”

The memo further argued that Roe, while not beyond criticism, had a grounding in constitutional law “stronger than it currently seems fashionable to recognize.” Still, the clerk allowed that if Souter felt it prudent, concerns over stare decisis would be less severe with “a relatively minor adjustment of Roe,” namely, replacing the trimester framework with the “undue burden” standard of regulation that Justice O’Connor had endorsed a decade before; any law that unduly burdened a woman’s right to obtain an abortion would be invalid.

All of this Souter read. And he had concluded that the Court ought to reaffirm Roe when, in conference two days after oral arguments in Casey, a majority of his fellow justices concluded the opposite.

Souter was dismayed. And as Rehnquist, the Chief Justice, prepared to write a majority opinion in support of Pennsylvania and its abortion regulations, Souter, as I note in my book, set out to rescue Roe, reaching out to Justice O’Connor, and then, with her, to Justice Kennedy.

O’Connor and Kennedy were unlikely allies of Roe. The first had told a Senate committee of her own “abhorrence of abortion as a remedy.” The second, in joining the majority in ruling on Webster v. Reproductive Health Services just a few years earlier in 1989, had expressly detailed constitutional frustrations with Roe.

But O’Connor – who was married – was troubled by the law which required a woman seeking an abortion to first notify her husband. And Kennedy now wanted to find “some stable, defensible middle ground on Roe,” as Lazarus wrote, “an endeavor Kennedy could sell to himself as truly judicious and advancing the country’s welfare.” And so, the trio of justices, working in stealth apart and together, wrote an opinion that upheld Roe at its core. “Rehnquist and Scalia were stunned,” observed the Los Angeles Times. “So, too, was Blackmun” – the justice who had written for the majority in Roe.

A ruling that spoke not of privacy, but equality

The ruling was a compromise. Half of it, which Blackmun and John Stevens now joined, upheld the “essential holding of Roe,” namely, the right to an abortion through viability. The other half adopted a new subjective standard of abortion regulation, O’Connor’s “undue burden.” Souter, O’Connor and Kennedy concluded that four of the five Pennsylvania regulations cleared that standard, and that became the decision of the Court: Blackmun and Stevens joined the troika in striking down the spousal notification requirement, and the remaining four justices voted with them to uphold the other regulations.

The “undue burden” standard, which was now effectively the law, did away with the trimester framework of Roe, which left abortion to the discretion of a woman and her doctor during the first trimester, but permitted the state to regulate (if not outlaw) it during the second. Henceforth, states could impose abortion regulations from the point of conception. “Even in the earliest stages of pregnancy,” the ruling explained, “the State may enact rules and regulations designed to encourage her to know that there are philosophic and social arguments of great weight that can be brought to bear in favor of continuing the pregnancy to full term …”

Still, the great upshot of Casey was that it preserved the essence of Roe. And on June 29, 1992, O’Connor, Kennedy and Souter each read aloud portions of their joint opinion. It was Souter who spoke the meat of it. “The ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation,” he said, “has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.”

It was a remarkable sentence. For it spoke not of privacy – the legal ground that Roe was built upon – but equality, the principle that future Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and others had famously asserted ought to undergird Roe instead.

Souter, in black robe and graying hair, then turned to the legal underpinning of Casey – the reliance on precedent that, he said, now called upon both sides of the abortion debate “to end their national division by accepting a common mandate rooted in the Constitution.” He continued, reading aloud a passage that resonates today:

The Court is not asked to do this very often, having thus addressed the Nation only twice in our lifetime, in the decisions of Brown and Roe. But when the Court does act in this way, its decision requires an equally rare precedential force to counter the inevitable efforts to overturn it and to thwart its implementation. Some of those efforts may be mere unprincipled emotional reactions; others may proceed from principles worthy of profound respect.

But whatever the premises of opposition may be, only the most convincing justification under accepted standards of precedent could suffice to demonstrate that a later decision overruling the first was anything but a surrender to political pressure, and an unjustified repudiation of the principle on which the Court staked its authority in the first instance. So to overrule under fire in the absence of the most compelling reason to re-examine a watershed decision would subvert the Court’s legitimacy beyond any serious question.

Souter finished speaking. He had been true to himself and to the example of his hero, Justice Harlan. And in so doing, he had built upon the arguments of his clerk, that unnamed legal scholar whose analysis prefigured key elements of the Court’s historic decision.