Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Scientists have uncovered the fossil of a bird that lived 120 million years ago, and it definitely had flair, including unusually long tail feathers. These flashy feathers probably didn’t help the bird achieve aerodynamic flight, but they might have helped him find a mate, according to new research.

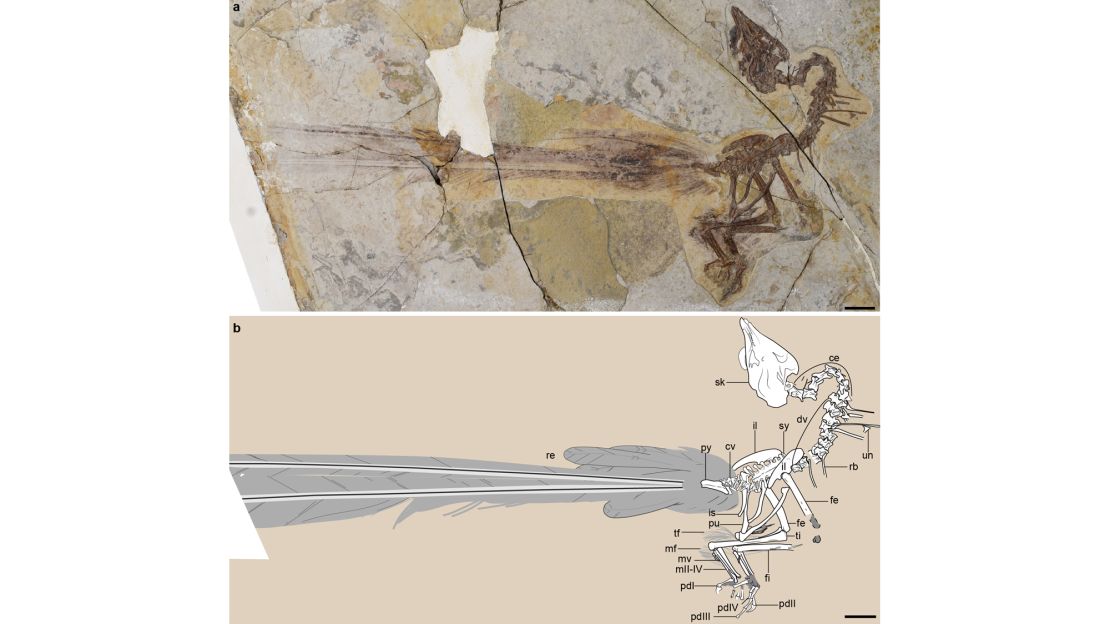

The fossil was discovered in the Jehol Biota – an ecosystem dating back 133 to 120 million years ago – in northeastern China, and the deposits there have been a treasure trove of fossil discoveries, including examples of ancient flight. The researchers dubbed the species Yuanchuavis after Yuanchu, a mythological Chinese bird.

The bird was likely comparable in size to a modern blue jay. However, its tail reached more than 150% the length of its body. The study published Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

“We’ve never seen this combination of different kinds of tail feathers before in a fossil bird,” said Jingmai O’Connor, study author and a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, in a statement. O’Connor is the associate curator of fossil reptiles at the Field Museum’s Negaunee Integrative Research Center.

“It had a fan of short feathers at the base and then two extremely long plumes,” O’Connor said. “The long feathers were dominated by the central spine, called the rachis, and then plumed at the end. The combination of a short tail fan with two long feathers is called a pintail, we see it in some modern birds like sunbirds and quetzals.”

Yuanchuavis likely flew similarly to a quetzal, a forest-dwelling bird that doesn’t have the most exceptional flight capabilities, O’Connor said. The pintail feathers were large enough to create significant drag, despite the fact that they were lightweight.

Short tails are associated with birds that live in harsh environments, where they depend on their ability to fly as a survival skill, like seabirds. The more elaborate tails are often found on birds living in forests.

“This new discovery vividly demonstrates how the interplay between natural and sexual selections shaped birds’ tails from their earliest history,” said Wang Min, study author and researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a statement. “Yuanchuavis is the first documented occurrence of a pintail in Enantiornithes, the most successful group of Mesozoic birds.”

Scientists recognized two different tail structures from other enantiornithines that are combined in Yuanchuavis.

“The tail fan is aerodynamically functional, whereas the elongated central paired plumes are used for display, which together reflect the interplay between natural selection and sexual selection,” Wang said.

Animals not only adapt to survive but to help their particular species persist. In this case, Yuanchuavis developed tail feathers that hindered its flying abilities and made it more noticeable to predators. The discovery highlights just how important sexual selection is during evolution, O’Connor said.

“Scientists call a trait like a big fancy tail an ‘honest signal,’ because it is detrimental, so if an animal with it is able to survive with that handicap, that’s a sign that it’s really fit,” O’Connor said. “A female bird would look at a male with goofily burdensome tail feathers and think, ‘Dang, if he’s able to survive even with such a ridiculous tail, he must have really good genes.’”

Elaborately plumed birds tend to be males. They’re so focused on maintaining their feathers that they don’t make especially good caregivers to offspring. Flashy feathers would also draw predators toward nests. But the more plain females stick with their chicks and take care of them.

Despite the fact that enantiornithines initially thrived, they did not survive the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. It’s most likely due to the fact that they lived in forests, which burned after the asteroid struck, or because they had not adapted to grow quickly.

“Understanding why living birds are the most successful group of vertebrates on land today is an extremely important evolutionary question, because whatever it was that allowed them to be so successful probably also allowed them to survive a giant meteor hitting the planet when all other birds and dinosaurs went extinct,” O’Connor said.

Fossils don’t always reveal the ways that sexual selection shapes a species.

“The well-preserved tail feathers in this new fossil bird provide great new information about how sexual selection has shaped the avian tail from their earliest stage,” Wang said.

“The complexity we see in Yuanchuavis’s feathers is related to one of the reasons we hypothesize why living birds are so incredibly diverse, because they can separate themselves into different species just by differences in plumage and differences in song,” O’Connor said. “It’s amazing that Yuanchuavis lets us hypothesize that that kind of plumage complexity may already have been present in the Early Cretaceous.”