Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Bringing extinct creatures back to life is the lifeblood of science fiction. At its most tantalizing, think Jurassic Park and its stable of dinosaurs.

Advances in genetics, however, are making resurrecting lost animals a tangible prospect. Scientists have already cloned endangered animals and can sequence DNA extracted from the bones and carcasses of long-dead,extinct animals.

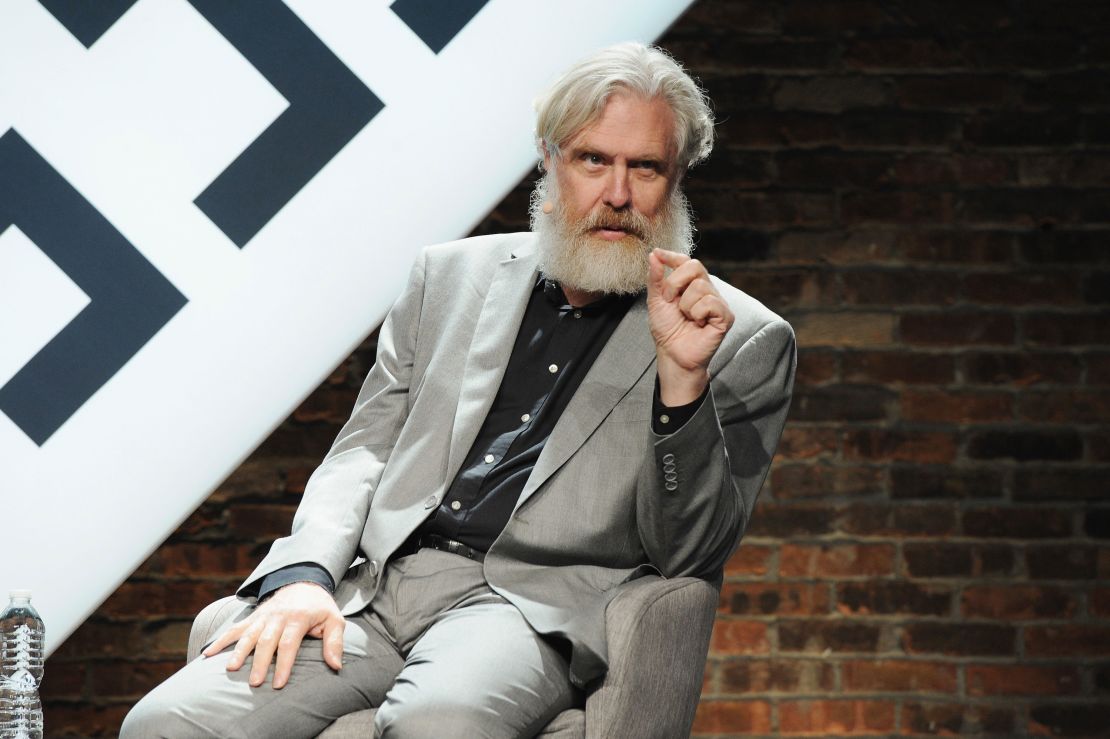

Geneticists, led by HarvardMedical School’s George Church, aim to bring the woolly mammoth, which disappeared 4,000 years ago, back to life, imagining a future where the tusked ice age giant is restored to its natural habitat.

The efforts got a major boost on Mondaywith the announcement of a $15 million investment.

Proponents say bringing back the mammoth in an altered formcould help restore the fragile Arctic tundraecosystem, combat the climate crisis,and preserve the endangered Asian elephant, to whom the woolly mammoth is most closely related. However, it’s a bold plan fraught with ethical issues.

The goal isn’t to clone a mammoth – the DNA that scientists have managed to extract from woolly mammoth remains frozen in permafrost is far too fragmented and degraded – but to create, through genetic engineering, a living, walking elephant-mammoth hybrid that would be visually indistinguishable from its extinct forerunner.

“Our goal is to have our first calves in the next four to six years,” said tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm, who with Church has cofounded Colossal, a bioscience and genetics company to back the project.

‘Now we can actually do it’

The new investment and focus brought by Lamm and his investors marks a major step forward, said Church, the Robert Winthrop Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School.

“Up until 2021, it has been kind of a backburner project, frankly. … but now we can actually do it,” Church said.

“This is going to change everything.”

Church has been at the cutting edge of genomics, including the use of CRISPR, the revolutionary gene editing tool that has been described as rewriting the code of life, to alter the characteristics of living species. His work creating pigs whose organs are compatible with the human body means a kidney for a patient in desperate need of a transplant might one day come from a swine.

“We had to make a lot of (genetic) changes, 42 so far to make them human compatible. And in that case we have very healthy pigs that are breeding and donating organs for preclinical trials at Massachusetts General Hospital,” he said.

“With the elephant, it’s a different goal but it’s a similar number of changes.”

The researchteam hasanalyzed the genomes of 23 living elephant species and extinct mammoths, Church said. The scientists believe they will need to simultaneously program “upward of 50 changes” to the genetic code of the Asian elephant to give it the traits necessary to survive and thrive in the Arctic.

These traits, Church said, include a 10-centimeter layer of insulating fat, five different kinds of shaggy hair including some that is up to a meter long, and smaller ears that will help the hybrid tolerate the cold. The teamalso plans to try to engineer the animal to not have any tusks so they won’t be a target for ivory poachers.

Once a cell with these and other traits has successfully been programmed, Church plans to use an artificial womb to make the step from embryo to baby – something that takes 22 months for living elephants. However, this technology is far from nailed down, and Church said they hadn’t ruled out using live elephants as surrogates.

“The editing, I think, is going to go smoothly. We’ve got a lot of experience with that, I think, making the artificial wombs is not guaranteed. It’s one of the few things that is not pure engineering, there’s maybe a tiny bit of science in there as well, which always increases uncertainty and delivery time,” he said.

Skepticism

Love Dalén, professor of evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm who works on mammoth evolution, believes there is scientific value in the work being undertaken by Church and his team, particularly when it comes to conservation of endangered species that have genetic diseases or a lack of genetic variation as result of inbreeding.

“If endangered species have lost genes that are important to them … the ability to put them back in the endangered species, thatmight prove really important,” said Dalén, who is not involved in the project.

“I still wonder what the bigger point would be. First of all, you’re not going to get a mammoth. It’s a hairy elephant with some fat deposits.

“We, of course, have very little clue about what genes make a mammoth a mammoth. We know a little, bit but we certainly don’t know anywhere near enough.”

Others say it’s unethical to use living elephants as surrogates to give birth to a genetically engineered animal. Dalén described mammoths and Asian elephants as being as different as humans and chimpanzees.

“Let’s say it works, and there’s no horrible consequences. No surrogate elephant moms die,” said Tori Herridge, an evolutionary biologist and mammoth specialist at the Natural History Museum in London, who is not involved in the project.

“The idea that by bringing mammoths back and by placing them into the Arctic, you engineer the Arctic to become a better place for carbon storage. That aspect I have number of issues with.”

Some believe large that, before their extinction, grazing animals like mammoths, horses and bison maintained the grasslands in our planet’s northern reaches and kept the earth frozen underneath by tramping down the grass, knocking down trees and compacting snow. Reintroducing mammoths and other large mammals to these places will help revitalize these environments and slow down permafrost thaw and the release of carbon.

However, both Dalén and Herridige said there was no evidence to back up this hypothesis, and it was hard to imagine herds of cold-adapted elephants making any impact on an environment that’s grappling with wild fires, riddled with mires and warming faster than anywhere else in the world.

“There’s absolutely nothing that says that putting mammoths out there will have any, any effect on climate change whatsoever,” Dalén said.

Ultimately, the stated end goal of herds of roaming mammoths as ecosystem engineers may not matter, and neither Herridge nor Dalén knock Church and Lamm for embarking on the project. Many people might be happy to pay to get up close to a proxy mammoth.

“Maybe it’s fun to showcase them in the zoo. I don’t have a big problem with that if they want to put them in a park somewhere and, you know, make kids more interested in the past,” Dalén said.

There is “zero pressure” for the project to make money, Lamm said. He is banking on the endeavor resulting in innovations that have applications in biotechnology and health care. He compared it to how the Apollo project got people caring about space exploration but also resulted in a lot of incredible technology, including GPS.

“I am absolutely fascinated by this. I’m drawn to people who are technologically adventurous and it is possible it will make a positive difference,” Herridge, the mammoth expert, said.