The “Harlem Hellfighters” helped the US win World War I. The Black infantry unit was one of the most decorated regiments at the time, even as most of its members were met with racism and disregard upon their return home.

Now, more than 100 years after the regiment’s surviving members came home to a country that largely ignored their contributions to the war effort, the Hellfighters will receive some national recognition.

President Joe Biden earlier this month signed the Harlem Hellfighters Congressional Gold Medal Act, which will posthumously award Congress’ most vaunted symbol of appreciation to the World War I unit.

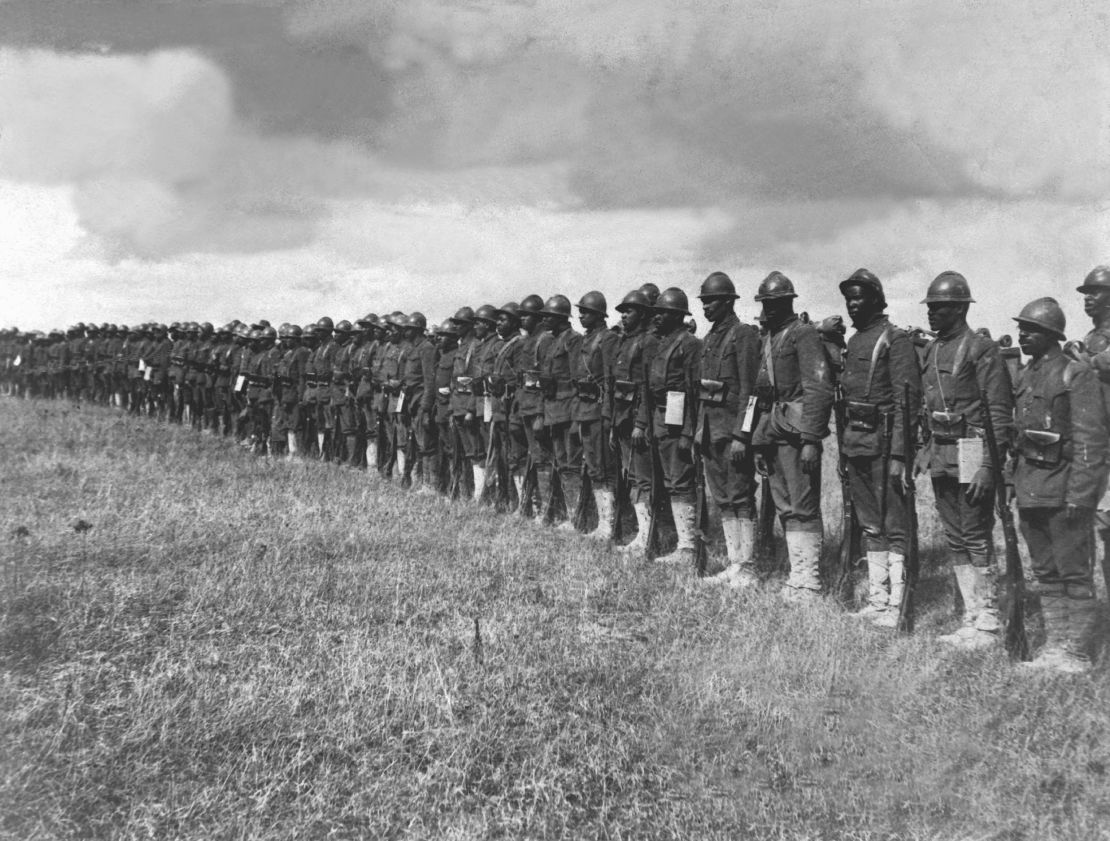

“Hellfighters” was the nickname for the members of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an infantry unit made up of Black soldiers, mostly New Yorkers. Though the unit suffered enormous casualties – around one-third of the entire regiment – they received several prestigious honors from the French military, including the Croix de Guerre.

Democratic Rep. Tom Suozzi of New York, who sponsored the bill, said he was inspired to pursue the Congressional Gold Medal for the Hellfighters after meeting with the family of one veteran, Lt. Leander Willet, who posthumously received a Purple Heart in 2019.

“It is never too late to do the right thing,” Suozzi said in a statement. “Awarding the Harlem Hellfighters the Congressional Gold Medal ensures that generations of Americans will now fully comprehend the selfless service, sacrifices, and heroism displayed by these men in spite of the pervasive racism and segregation of the times.”

How the Hellfighters helped win WWI

The members of the 369th Infantry Regiment were among 200,000 Black soldiers who served in World War I, 42,000 of whom served in combat, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). At the time, the military was still segregated.

Most of the members belonged to the 15th New York National Guard Regiment, and many of them lived in Harlem, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Their commander was the White former Nebraska National Guard Col. William Hayward, who told the men while training in Jim Crow-era South Carolina to avoid retaliating when confronted by racist soldiers.

Author Max Brooks, who wrote a graphic novel on the Hellfighters, said in a 2014 CNN appearance that the Hellfighters were “set up to fail by their own government” and did not receive “the kind of valor, the kind of honor that they deserve.”

Though they were first assigned to “unloading ships and cleaning latrines” when they arrived in France, per Smithsonian Magazine, the regiment was reassigned to the French Army in 1918 partly because the French needed soldiers, but also because so many White US soldiers had refused to serve alongside them, according to the NMAAHC. Under the French, the men would fight on the front lines.

“We are now a combat unit,” Hayward wrote in a letter, according to Smithsonian Magazine. “Our great American general simply put the black orphan in a basket, set it on the doorstep of the French, pulled the bell, and went away.”

The Hellfighters likely earned the nickname from their German foes, according to the NMAAHC, for their tenacious fighting style. Take Privates Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, who fended off German soldiers with hand grenades and Johnson’s 9-inch knife one night in 1918. Johnson and Roberts, who was a teenager at the time, were awarded the Croix du Guerre for their bravery and were also the first African American soldiers to be decorated, the New York Tribune reported in 1919.

The French welcomed the Hellfighters warmly, according to several historical accounts, celebrating in the streets when they marched through towns and eagerly attending performances by the regiment’s esteemed military jazz band. When the unit appeared in Lyons, the Kansas City Sun reported at the time that “no regiment received a greater welcome than did this crack Afro-American regiment.”

It seemed as though the men would get a similar reception in the US – in all, 171 members of the unit received medals, per the NMAAHC, and one headline published in 1919 read that their “glorious fighting record gives them the right to benefits of full citizenship.” But the racism and segregation enshrined in American law did not end when the welcome-home parades did.

The Hellfighters’ legacy endures

The Hellfighters helped change the tide of World War I and even introduced jazz to a very receptive French audience.

But the contributions of the Hellfighters were largely ignored for decades until recently. In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded Johnson, who advocated on behalf of Black soldiers before his untimely death in his early 30s, a posthumous Medal of Honor. And in 2017, Will Smith’s production company began pursuing a TV series adaptation of Brooks’ graphic novel on the Hellfighters, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

The Hellfighters’ medal will be given to the Smithsonian, according to the bill Biden signed this month.