On August 15, Khalida Popal watched from Denmark as her country fell into the grip of the Taliban.

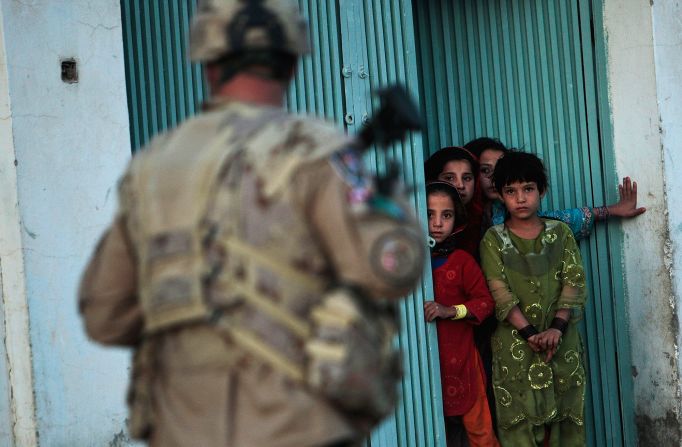

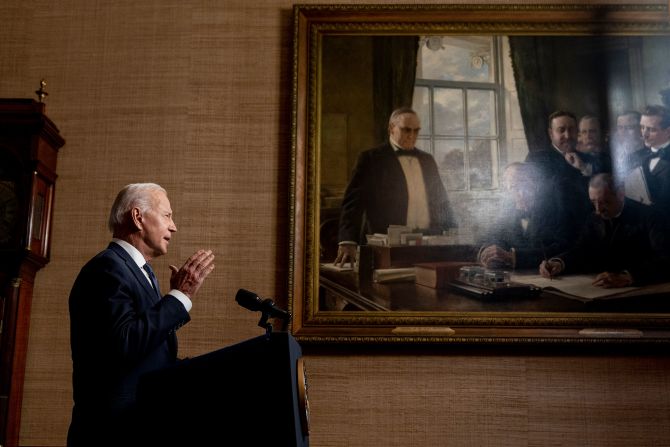

Following nearly two decades of conflict, the insurgent militant group reclaimed Afghanistan’s capital and took over the country’s presidential palace, barely a month after the US began the final withdrawal of military troops from its longest running war.

Earlier that day, ousted President Ashraf Ghani fled Afghanistan to the UAE as the Taliban broke through Kabul, and the US completed its evacuation of its embassy in Afghanistan, lowering the American flag at the diplomatic compound.

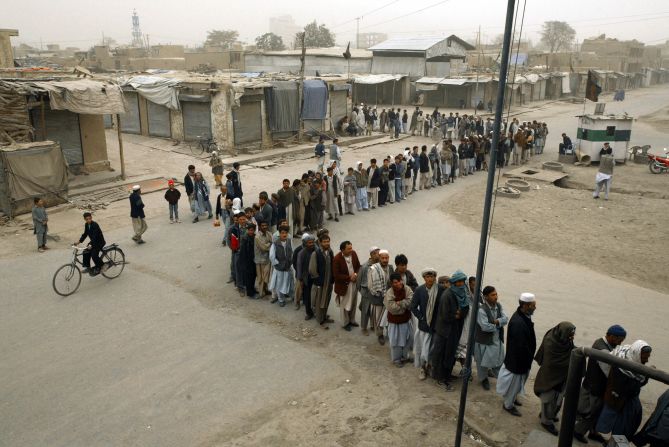

In the last few days, images have emerged of people clambering over one another at Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport, trying to cling onto planes as they leave the runway in a desperate attempt to flee the country.

With foreign governments flying out their citizens first, they provide little hope to the Afghan people to whom many feel they owe protection for helping them in the 20-year conflict.

“I feel heavy in my chest. I am sad. I feel sleepless and it hurts,” former Afghan football player Popal tells CNN Sport’s Amanda Davies.

“I just want my phone to be away so I can just feel freedom in my brain, but I cannot. I have been stuck with my phone the past few weeks, watching the country collapsing, watching our enemies,” she adds.

‘It’s traumatizing for me’

This isn’t the first memory Popal has of her country being threatened by foreign invasion and guerrilla war groups.

In 1989, the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan, after they had invaded and occupied the country for 10 years.

Seven years later, when Popal was nine years old, the newly-formed Taliban seized Kabul and ruled Afghanistan for the next half-decade.

“It’s traumatizing for me and […] my generation,” she says. “Our childhood is repeating again, and the history is repeating again.”

During their rule, the Taliban declared the country the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, imposing strict laws on women – forced head-to-toe coverings, the prohibition of school or work outside the home and being banned from traveling alone.

“It was very dark, scary time. I remember my childhood at the age of eight, nine years old, when Taliban took over the country, when they started […] killing […] and putting people in prison,” Popal says.

She says that, as her family had been beaten by the Taliban – some “shot dead” – they would live in fear, “being so scared, sitting at home” and “waiting that, any time, the door will be knocked and they will be taken.”

“I remember asking the questions because I had so many questions on it as every other kid, not understanding […] the politics. Asking a lot of question, ‘My father, why don’t they let me go to school?’ How about if I want […] to play football outside, if I want to go and meet my friends in the street? Why? Why my mom is not allowed to go to work?” Popal tells Davies.

In the shadow of the Taliban

Popal says that after the Taliban began to lose its major strongholds with the invasion of US and coalition forces in 2001, she didn’t expect them to return to power.

“We were never prepared,” she says. “All the Afghan community, everybody is shocked.

“Of course, Taliban has […] always existed. They have been fighting for such a long time around the borders, around the rural areas of Afghanistan. There was always threat.”

When Popal was 16 a few years later, she started to play football in the shadow of the Taliban, who had prohibited women from taking part in sports or going to stadiums.

Even though the group had been expelled from power, they still waged war against coalition forces and the US-backed Afghan government, and therefore had socio-political influence in some parts of the country.

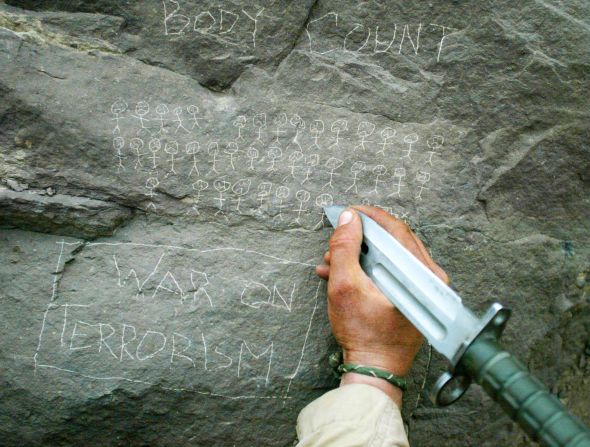

20 years in Afghanistan: America's longest war

In 2007, she founded the Afghan women’s national football team and went on to captain her side, eventually becoming the first woman to be employed by the Afghanistan Football Federation.

However, as Popal continued to speak out, her global presence grew – as did the threats against her.

In 2010, she decided to leave Kabul, making her way to Pakistan and India, before eventually finding asylum in Denmark.

“We had to escape,” she says. “I remember like going to this scary and dangerous way […] to a safe place to seek protection and live as a refugee in Pakistan.”

‘Our players are totally helpless’

Since then, Popal has continued to use sport as a platform for activism, launching the Girl Power Organisation in 2014 to support refugees and migrants and advocating for women’s rights at multiple conferences for organizations such as FIFA, UEFA and the United Nations.

“We have given so many sacrifices in the past 20 years of our life […] to achieve this collective, the pride of representing our country, the ownership of representing the national team of Afghanistan,” she says.

“We used football […] to stand for our right as women […] but also to be the voice for voiceless sisters that they were still living under the regime of Taliban,” Popal adds. “We were following the news, how they were stoned, how they were beaten, how they were beaten to death.”

“We stood up. We said, no matter if you shut our sister there, no matter how many of us being killed, we will stand together. We are stronger. We will not give up because we had trust.”

Now, it seems the pride Popal once felt in representing Afghanistan on the world stage is but a fading memory.

Instead, her mind is occupied with the thought of the female footballers who are still stranded in Afghanistan.

“Our players are totally helpless,” Popal says. “We have really fought so hard to earn the name […] on the jersey and the badge on our chest and wear the uniform of the national team and represent our country in an international level.”

“What hurts me the most is when I have been for the past few days, I have been calling them and telling them to burn down your uniform, try to remove anything that you have from the national team so they don’t identify if they come to your house. Take down your social media, try to be silent, try to hide your identity, remove your identity,” she adds.

‘They should not be forgotten like this’

For Popal, one of the greatest emotional setbacks of the past few decades has been entering the new millennium “with a lot of great hope for the future,” only to end up feeling cast aside by the global community.

“That time I was a teenager and my generation and the new generation did everything possible to actively participate in […] building the country […] the community, the society, and also being thankful, showing to the international committee, that your time is not wasted in our country,” she says.

“Everything was forgotten,” Popal continues. “The international community […] entered our country with the words, with big sentences, words defending the right of women of Afghanistan, we will not let the women of Afghanistan to live in darkness of Taliban again.”

“We have done everything to be part of the growth and progress to also represent the new image of Afghanistan […] of the strong woman of Afghanistan, but now the world [has] forgotten us.

“Thinking about every individual that I have been working with – I know them, my friends, my family members and all these amazing women that has been part of the growth and progress is in the hands of [the] enemy, and without any protection.”

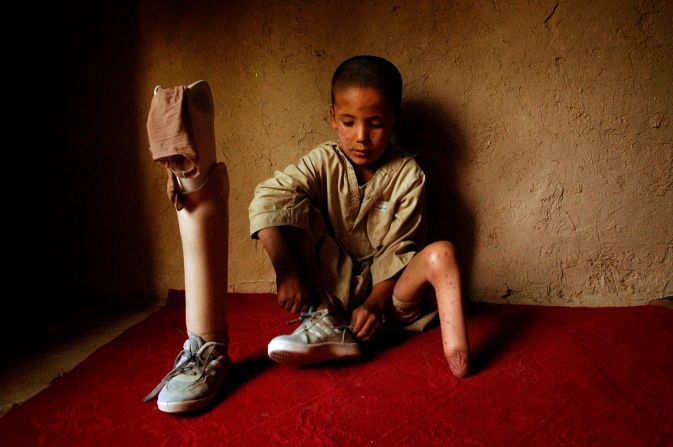

In pictures: Afghanistan in crisis after Taliban takeover

Despite her emotional torment, Popal remains faithful to her country and the promise of a better tomorrow.

“My message to every […] individual and to organizations and to governments is that, just don’t forget the women of Afghanistan, they have done nothing wrong and they should not be forgotten like this, and they need support, they need protection,” she says.

“Please be their voices, be the voice for those voiceless and helpless women in the country.”