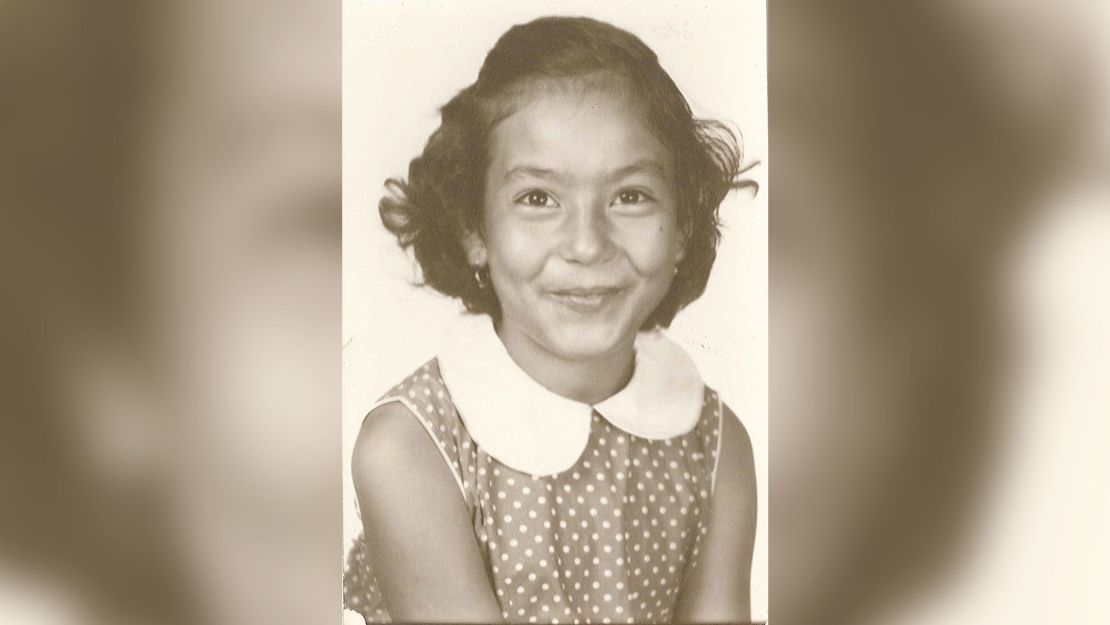

Decades afterLupe Alemán was forced to repeat the first grade three times, her son is making it his life’s work to reverse racial inequity in schools.

Enrique Alemán Jr., 50, has spent the past few years talking with numerous students in Texas and across the United States about how his mother and other Mexican American children in Driscoll, Texas, were treated in the 1950s by school officials who claimed they couldn’t speak or understand English.

But a controversial law that goes into effect on September 1 will restrict how social studies teachers in the Lone Star State discuss race. The law could also make it potentially difficult to discuss why Lupe Alemán and at least seven other children went to federal court in the year after the landmark US Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

“I think it’s very bad for students of all races to not talk about the uncomfortable aspects of our history. And it’s especially bad for Latino youth to not understand that Texas has been a violent, racist, discriminatory place to live,” Alemán Jr. told CNN.

While Texas lawmakers have been embroiled in a battle over election laws in recent months, “critical race theory” legislation has been another priority for Republicans in the state. In June, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott signed into law HB3979, and an expanded version of that bill is currently being considered by the state Senate in a second special legislative session that began on August 7.

HB3979 states that social studies teachers can’t “require” or include in their courses, the concept that “one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex” or the concept that “an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.”

It also notes that “a teacher may not be compelled to discuss a particular current event or widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs.” Teachers, according to the bill, also can’t require or give extra credit for a student’s political activism.

The legislation proposed by Senate Republicans, SB3, intends to extend the restrictions to all teachers, regardless of subject or grade level.

Mexican American children sued their school and won

In 1955, a group of children and their parents sued the Driscoll Consolidated Independent School District for placing Mexican American children in the first grade for a period of three years solely because they were of Mexican descent, according to the federal lawsuit.

The school district in Driscoll, a town of nearly 800 people about two hours south of San Antonio, said in court that students were only placed in separate classrooms because of their lack of English proficiency. School officials said it deprived other students from teachers’ attention and instruction, and not because of their country of origin, court documents show.

After several students appeared in court to testify that they were fluent in English, US District Judge James V. Allred ruled in 1957 that it was unreasonable to place students in separate classrooms based their race or origin.

CNN reached out to the current superintendent and board members of the Driscoll Independent School District for comment multiple times.

Alemán Jr. was about 10 years old when he picked up his mother’s high school yearbook and his mother shared two details of her life that, at the time, he didn’t comprehend.

As a young girl in Driscoll, Lupe Alemán was part of a court case, and by the time she graduated high school, she was nearly 21 years old, Alemán Jr. says his mother told him.

It was more than two decades later that Alemán Jr. realized what his mother was referring to.

Alemán Jr. was 33 years oldwhen he saw a documentary on TV about Hector P. Garcia, a Texas civil rights advocate who founded the American G.I. Forum, a group that helped Mexican American veterans fight discrimination. The documentary recounts Garcia’s life and activism, including how the group filed a federal lawsuit in the mid-1950s against the school district in Driscoll.

“I immediately had a flashback and remembered what my mother told me,” he said.

His mother, who was born in Driscoll, lived there until she was a young adult and would have been about 9 years old when the lawsuit was filed, Alemán Jr. said.

But he couldn’t just pick up the phone and ask his mother about the case. His mom had died a few months before he watched the documentary, he said.

“I was amazed and I was upset,” Alemán Jr. said, adding that his mother and two of his aunts testified in court. “I didn’t understand why nobody ever talked about it.”

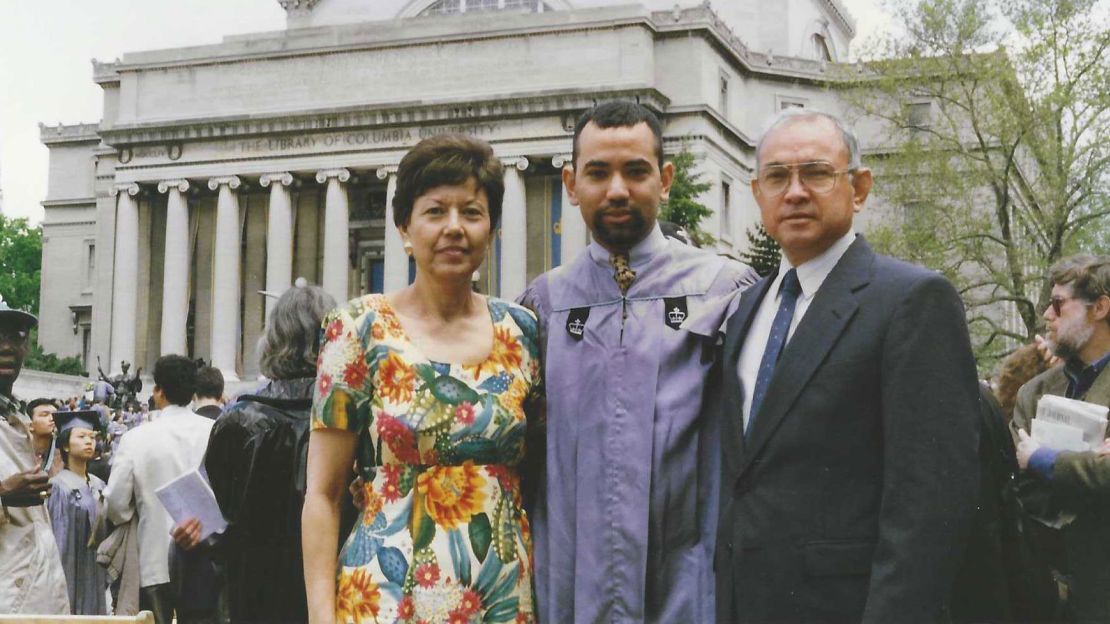

As Alemán Jr. continued his education and he focused his research on the inequities that Black and brown students face in school, he couldn’t forget about his family’s history.

In 2012, he traveled across Texas to meet several of the children who testified along with his mother for the Hernandez v Driscoll CISD case and produced a documentary called “Stolen Education.”

He learned that some were punished for speaking Spanish in school or had seen classmates being paddled by teachers. Some graduated high school and others dropped out of school to work or join the military, he said.

They went on with their lives, Alemán Jr. says, but “there’s still something in them that feels like they didn’t reach their full potential because of the way that they started out.”

There’s been a long fight for ethnic studies in Texas

Educators and advocates say they are concerned the new law will have negative implications for the decades-long effort to make the history being taught in Texas schools more inclusive.

More than 52% of the 5.3 million children enrolled in kindergarten to 12th grade across Texas in the last school year were Hispanic or Latino, Texas Education Agency (TEA) data shows.

Yet, curriculum standards to teach Mexican American studies, only as an elective high school course, were only approved in 2018 after years of debate.

Sonia Hernandez, an associate professor of history at Texas A&M University, who works with the nonprofit Refusing to Forget to shine light on the killings of Mexican Americans by Texas Rangers in the 1910s and 1920s, said she was saddened to see that an “unfounded idea” could become a set back for advocates and educators in the state.

“Just so many years of great effort are being pushed aside because of the unfounded idea that if we talk about issues of racial inequality, if we talk about how certain groups of people were marginalized and were treated as second- class citizens – even if they were in fact US citizens – that would lead to some kind of unpatriotic history,” Hernandez said.

“We are doing our students a disservice, we are telling them that we think they’re not intellectually equipped to understand a complex history of their own country,” she added.

For Tony Diaz, an author and activist, the new law and efforts around the “critical race theory” legislation echoes the sentiment behind the Arizona law that banned Mexican American studies in public schools about a decade ago.

“Those same tendencies are back in a new form,” said Diaz, who campaigned against the ban in Arizona schools by launching Librotraficante, a caravan to take books banned under the same law to Arizona.

The Texas law intends to intimidate teachers, Diaz says, and it will take similar “very profound grassroots campaign” to overturn it.

Weeks before the new law goes into effect, it’s still unclear how schools will implement it. The TEA has not yet issued guidance for schools and the agency hasn’t yet responded to CNN’s request for comment.

Angela Valenzuela, an education policy professor at the University of Texas, said the law doesn’t address how schools will implement or enforce it.

“I think ultimately it is intended to create division at the grassroots level to empower parents that feel their children are being hurt by either teaching concepts like white supremacy, white privilege, the history of racism and slavery,” Valenzuela said.

For Alemán Jr., who is now a Lillian Radford endowed professor of education at Trinity University and teaches classes for education leaders, the educational system in the state has in part “never wanted Latinos, African Americans and women to even know their own part” in history.

Learning what happened to his mother and other Mexican American children in Driscoll changed the purpose of Alemán’s work. It also made him feel close to his mom even decades after she passed away.

It’s empowering to know where you come from and that feeling, he says, it’s something he hopes more Latinos and students of color can feel while they are in school.