I wince every time I see footage of the Beirut port blast.

In the leadup to its anniversary my colleagues and I have had to pore over hours of video of the explosion and its aftermath. It’s not an easy task.

I was at my desk in CNN’s Beirut bureau, contemplating what to do after work on a hot August evening, when I felt the building shake.

An earthquake, I thought.

As I crouched down to take cover, I heard a huge explosion, followed by a tide of shattering glass.

I stumbled from room to room in a daze, stepping over twisted aluminum window frames, cables, chairs and broken equipment.

Was it a car bomb? I asked myself. An airstrike?

I looked outside and saw a strange orange-red cloud floating overheard. Below in the street, car alarms were squawking in a cacophonous chorus, the air full of dust, people were running around, shouting in confusion.

I called CNN producer Ghazi Balkiz. He answered, only to say he was OK but that was it.

Next, I tried calling our cameraman, Richard Harlow. No answer. I called again and again. Still no answer. Richard eventually made it back to the office, his right hand a bloody mess, and a gaping wound in his leg which he only discovered hours later, numbed by the shock and adrenalin of the moment.

Ghazi showed up later, after he’d taken his wife Sally to a chaotic hospital to be treated for multiple wounds caused by flying glass. The scenes from that hospital, he said, were worse than any he had seen covering the wars in Syria and Iraq.

In pictures: Huge explosion rocks Beirut

Everyone who survived the events of August 4, 2020, in Beirut vividly recalls the shock, bewilderment and confusion they felt in the moments after the blast.

Since then, those emotions have been replaced by others – anger, rage and resentment – that the dangerous ingredients that caused it had lain so close to the heart of this bustling city for more than six years.

One year ago, at 6.08 p.m. on an otherwise unremarkable Tuesday, they detonated in a mushroom cloud of death and destruction – one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in history.

Since then, Lebanon has plummeted even deeper into an abyss of economic and financial oblivion, political paralysis, and despair which it had begun sinking into long before the explosion.

For those who lost loved ones, the blast, and their demands for justice and accountability, remain a constant.

On a hot, humid afternoon in late July, Elias Maalouf stands outside the Justice Ministry in Beirut holding up a photograph of his son, George, in military uniform.

George was killed when hundreds of tonnes of ammonium nitrate, stored in the port since it was confiscated in 2013, exploded leaving a 400-foot wide crater and a trail of destruction spreading more than 10 kilometers (6 miles) from the epicenter of the blast.

“Every day his mother cries and cries,” said Maalouf. “She asks, ‘Why doesn’t George come over for coffee? Why doesn’t he come over for the weekend?’”

George, 32, was engaged to be married. “I wanted him to fill our house with grandchildren,” his father said.

Maalouf says he searched for eleven days to find his son’s body.

He and the families of many of the others who died have gathered regularly to demand justice for the more than 200 people killed in the blast but, a year on, it remains elusive.

Investigation goes nowhere

The day after the explosion, Lebanon’s interior minister Mohamed Fahmi promised an investigation that he said would “be transparent, take five days, and any officials involved will be held accountable.”

The first judge appointed to lead the inquiry, Fadi Sawan, was dismissed after the politicians he wanted to press charges against took him to court. They argued he was incapable of impartiality because his house was damaged in the blast.

Another judge, Tariq Bitar, took his place. But when he asked to question senior officials, including the powerful head of public security General Abbas Ibrahim, the interior minister ruled that Ibrahim could not be subject to interrogation.

Dozens of members of parliament, representing almost every political party across the spectrum, signed a petition to take the case out of Judge Bitar’s hands and move it to a previously unknown “Judicial Council.” This sparked a social media campaign against the so-called “deputies of shame.”

A year on, the “rapid” and “transparent” investigation has gone nowhere. A report published by Human Rights Watch this week summed up some of the reasons why.

“In the year since the blast … a range of procedural and systemic flaws in the domestic investigation have rendered it incapable of credibly delivering justice. These flaws include a lack of judicial independence, immunity for high-level political officials, lack of respect for fair trial standards, and due process violations,” the report found.

“What I saw on 4 August killed my heart,” recalled Samia Doughan, holding a photograph of her husband Mohammad, who was killed in the blast. “I saw people in pieces,” she said. “I saw people mutilated while I was searching for my husband.”

Turning her anger on those who run the country, she said: “For 30 years they destroyed us, they made us beggars, they impoverished us, humiliated us, they murdered us.”

“They” are Lebanon’s political elite – a group of mostly men representing Lebanon’s 18 officially recognized religious sects. A power-sharing arrangement dating back to French colonial rule ensures that Lebanon’s spoils are divided among them – behind a fa?ade of democratic elections.

They’re a seductive lot, especially to Western media: Gracious, accessible, sophisticated, worldly, well-travelled, and often fluent in English and French, they dish out soundbites and insider gossip that guarantee an interesting article or report.

They’ve done well for themselves. Most are fabulously wealthy, living in splendid isolation in their luxury mansions, shielded from a populace reeling from one crisis after another.

But sometimes the sheer absurdity of that separation becomes vividly apparent.

Najib Mikati, Lebanon’s latest prime minister designate – the third to try and form a government in less than a year – recently appeared on Lebanese television to lament the lot of this cursed blessed land’s self-appointed leaders.

“We’re ashamed to walk in the streets,” he told local broadcaster MTV. “I want to go to a restaurant!” he said, the frustration in his voice clear. “We want to live!”

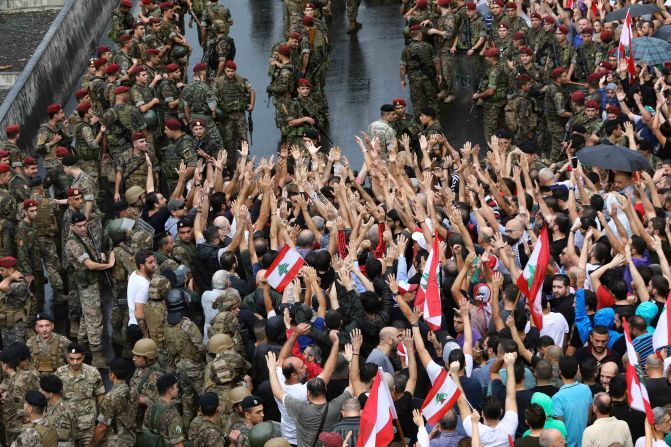

Since the October 2019 uprising that brought hundreds of thousands of people to the streets to protest Lebanon’s rotten political system, politicians and their spouses trying to dine out have become a favorite target of activists on the lookout to blame and shame those who have brought the country not just to the brink of ruin, but to ruin itself.

More than 50% of the population here now lives below the poverty line.

In the last two years Lebanon’s currency, the lira, has lost more than 90% of its value against the dollar. Two years ago, the minimum wage was equivalent to $450, now it is worth little more than $35.

Petrol is in short supply. Power cuts in Beirut often run for more than 20 hours a day. Thousands of businesses have closed. Unemployment has skyrocketed. Baby formula has disappeared from the market. People beg relatives visiting from overseas to bring life-saving medicines no longer available in pharmacies here.

In photos: Lebanon in crisis

All of which means that Mikati’s seemingly heartfelt plea – “We want to live!” – falls on deaf ears. Miqati, who hails from Tripoli, Lebanon’s poorest city, is the country’s richest man. Forbes Middle East estimates his net worth at $2.5 billion in 2021 – up by $400 million over the past year. Mikati was charged with corruption in 2019. He denied the allegations.

It seems self-awareness is the only thing the elite here lack.

Investigative journalist Riad Kobaissi has spent years digging up tales of corruption and mismanagement in Beirut’s port, which he says Lebanon’s various political factions have benefited from for years.

Kobaissi scoffs at the idea that any one faction is better or cleaner than another; he says the port catastrophe only made that more obvious.

“It’s a system failure,” he said. “And those who compose this system, despite the contradictions between them, are refusing to take responsibility for what happened.”

The port blast, he said, “is a direct result of the cohabitation of the mafia and the militia. Bottom line!”

‘Exponentially growing rage’

I first met Paul and Tracy Naggear 17 days after the port blast. They were still in a state of shock. Their three-year-old daughter, Alexandra, whom they had taken to the protests in 2019, was killed when the force of the explosion threw her across a room in their home, crushing her skull.

“We were aggressed and killed in our houses,” Paul said then, his face still bruised. “The only shelter, or the only place of safety that you thought was still there, we don’t have anymore. It’s just too much.”

“The rage we have today is exponentially growing, and reality is hitting us,” said Tracy.

I interviewed the couple again just days before the anniversary. Just before we turned off the camera, Paul said, “Wait, I have just one thing to say.”

“The only thing we ask for,” he said, “is for the European Union, France, Germany, the UK, the US, the UN to cut all diplomatic ties with this mafia ruling regime. They’re criminals. They’re traitors to the nation.”

“It’s ridiculous,” added Tracy. “The problem with this government is that they are not just criminals. They don’t know how to do things. They’re big failures. They don’t know how to manage electricity. They don’t know how to manage food. They don’t know how to manage health. It’s not just the economy. We have nothing in Lebanon.”

Paul brushed off the increasingly urgent calls from abroad for Lebanon’s squabbling politicians to form a government, implement reforms and root out rampant corruption.

“Please! Stop asking them to form a government,” he said. “Not these guys. They’re thugs. Garbage in, garbage out.”

Almost everyone in Beirut today is angry.

One of the slogans of the October 2019 uprising against the political elite was “Kulun yaani kulun” – “All of them, meaning all of them” – referring to the widespread demand that the entire political elite be swept away to allow Lebanon to realize its potential.

Yet all of them have managed to weather the triple storm of the past year – explosion, economic collapse, and coronavirus pandemic – intact and healthy, physically and mentally. Meanwhile the rest of the country struggles on, day by day.

Lebanon’s political class has failed, as Tracy Naggear, still mourning her daughter, said. A year on from the deadly blast, many here are asking when they will finally be held accountable.