CNN Original Series “Jerusalem: City of Faith and Fury” premieres tonight at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

When there’s news out of Jerusalem, reports often point to recent history to explain how such a complex web of communities came to reside in the Holy City.

But as historians describe in the CNN Original Series “Jerusalem: City of Faith and Fury,” the capital’s history of religious and political tension reaches far beyond the 20th century. It goes back millennia.

“The history of Jerusalem is a very complicated story,” says Laura Schor, a professor of history at Hunter College, in the CNN series. “And if you don’t know it in its complexity, it’s very hard to understand what’s going on there today.”

Part of that complexity revolves around theological fault lines, as Jerusalem is sacred ground for three major world religions: Jews, Christians and Muslims all have significant and separate ties to an area that today is roughly 50 square miles.

Then there’s the fact that Jerusalem is also “the center of national aspiration of two communities: the Israeli community and the Palestinian community,” explains Smith College religion professor Suleiman Mourad in the “Jerusalem” series. “That adds another layer of complexity.”

The challenge of unraveling centuries of conflict may be daunting, but “it’s impossible to imagine fixing the present and building a better future for Jerusalem without understanding the many stories of its past,” Schor adds.

“Jerusalem: City of Faith and Fury” offers a place to start by focusing on a half-dozen critical moments in the city’s evolution. Below is a timeline of those six key conflicts and rivalries, with expert commentary from the series.

Circa 1,000 B.C.: David vs. Goliath

The tale of an Israelite shepherd boy mightily defeating a giant is so legendary it’s still part of modern popular culture. Even those who’ve never read the Biblical text know its contours: David, portrayed as the ultimate underdog, takes down a towering, lethal foe named Goliath with nothing more than a slingshot and some faith.

Here’s why this well-known saga is so pivotal to the history of Jerusalem: In the Hebrew Bible, this isn’t just a feel-good story. It’s a foundational turning point in the establishment of a kingdom.

When David kills Goliath around 1000 B.C., this puts him on the path to become king over the 12 tribes of ancient Israel. Once he does, David takes Jerusalem as his capital city by force.

The walled enclave was built in a region called Canaan, territory “the Israelites believed God gave to them as the land that they were to inherit,” University of Iowa religious studies professor Robert Cargill explains. According to Biblical text, a native population called the Jebusites were already residing in David’s chosen capital, and as a result his conquest of Jerusalem is still debated today, adds historian and author Simon Sebag Montefiore.

39 B.C.: The rise and fall of Herod the Great

King David’s reign was followed by that of his son Solomon, whose crowning achievement was building the first temple on the site known today as the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif.

In the centuries that pass after their deaths, power structures shift but Jerusalem remains a desirable stronghold. And by 39 B.C., another ruler had ruthlessly taken control: Herod the Great.

Backed by the powerful Roman army, Herod violently installed himself on the throne and set about “making himself the most successful king, not just of Judea, but of the whole Mediterranean,” Montefiore explains.

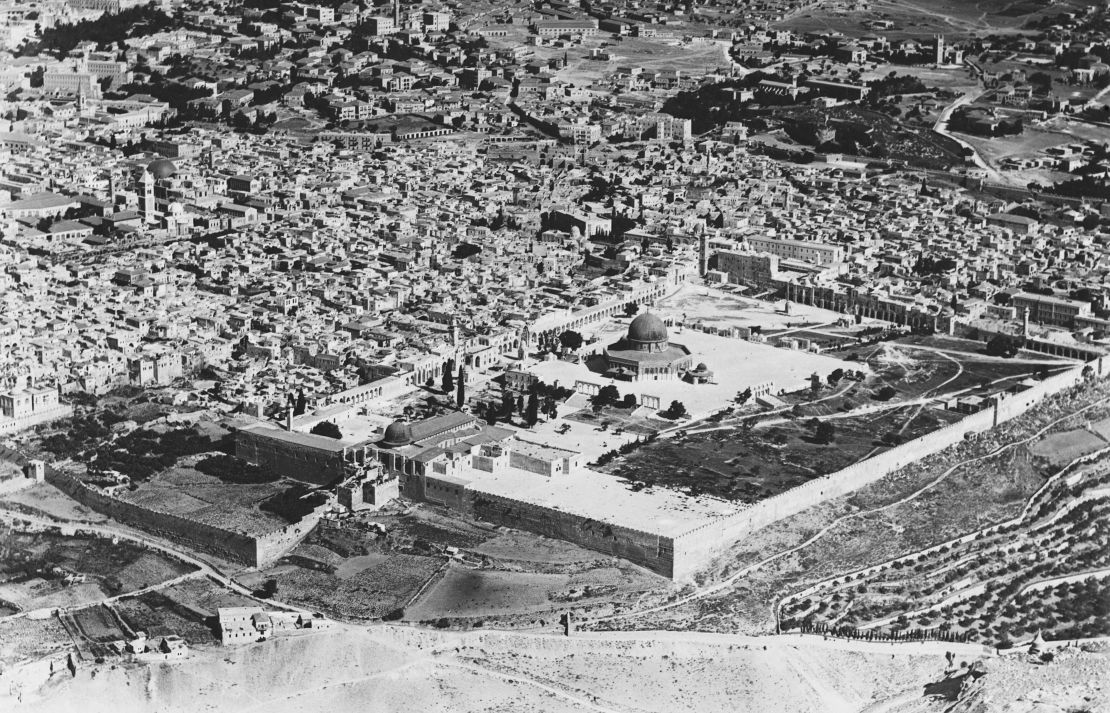

Herod’s reign is an influential moment in Jerusalem’s history, both because of the merciless political machinations that marked his rule – including a rivalry with Egypt’s Cleopatra – as well as his monumental efforts to rebuild Solomon’s temple and expand the city. It was Herod, author Montefiore says, who “created the Jerusalem we know today … The Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque are built on Herod’s sacred precinct.”

The end of his reign, however, was as ghastly as its start. After Herod’s death, “the Romans annexed the territory and ruled it through brutal procurators who were extremely corrupt, and who gradually tormented the Jews into rebelling,” Montefiore continues. “And to punish the Jewish people, they destroyed Jerusalem entirely, in 70 A.D. The temple was destroyed. All that’s left of it are the stones of the south, east, and western walls, which you can see today.”

1099 A.D.: The Crusades

More than 1,000 years after the death of Herod the Great, Jerusalem was caught between two other religions: Christianity and Islam.

Jerusalem is sacred for Christians because “this is a place where Jesus died, where he walked the Via Dolorosa,” notes Anthea Butler, an associate professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania, in the CNN series. “He was crucified outside of the city.”

“For Muslims,” adds historian Jonathan Phillips, “it’s the site of the prophet (Mohammed)’s Night Journey and his ascent to heaven.”

This leads to waves of horrendously violent wars, known as the Crusades, as Christians and Muslims battled for control of the Holy City.

“The legacy of the Crusades in Jerusalem, among the Arabs in general, is a horrible, horrible legacy,” says Smith College professor Mourad. “We have the way a European would remember it, as a chapter of Medieval Europe, and there is also the way the Arab, or the Muslim remembers it, as a form of pre-modern colonial attack and occupation.”

1914: The First World War

By the start of World War I, Jerusalem was part of the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with Germany.

On the other side stood the British Empire, which “badly wanted to control the Holy Land, to bring it under Christian influence at a time of Ottoman Islamic rule,” says Bruce Hoffman, the Director of the Center for Jewish Civilization at Georgetown University.

As the war unfolded, there was born what at first appeared an alliance, as Arabs in revolt against their Ottoman rulers found support from the British.

In reality, says Ali Qleibo, an anthropologist and writer for This Week in Palestine magazine, Arab rebels hoping to come out from under Ottoman rule “were lured and lied to by Britain. They thought it’s simply liberation; they did not know it was preparatory for an occupation.”

Britain struck a secret deal with France called the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which “essentially divided [the Ottoman Empire] of the Middle East into a British part, including most of Iraq, Jordan and Palestine, and a French part, which included Lebanon, Syria and part of Turkey,” Mourad says.

The new agreement made it no easier on Jerusalem. “To a large extent,” says Simon Davis, a professor of history at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center, “the main outcome of the First World War for Jerusalem was that the Israeli-Palestinian dispute that we know so much about today is really instituted, unwittingly to a degree, by British multiple promises.”

1948: Independence and defeat

Following the first World War, the Jewish population in Palestine began to grow by the tens of thousands, in particular as Jews fled the terror of Hitler’s regime in the 1930s.

At the time, Palestine was still under British rule, and tensions flared between all sides. Arab and Jewish communities each had separate nationalist visions of claiming Palestine as their homeland, and both populations wanted to see an end to the British administration.

Not long after the end of World War II, a beleaguered Britain made plans to pull out of Palestine, and the newly formed United Nations stepped in with a proposal to the question of who should control the territory.

“In 1947, the United Nations votes for the creation of a Jewish state and a Palestinian Arab state in Palestine, and they draw an incredibly unrealistic partition of the country,” says historian Simon Sebag Montefiore. The plan was opposed by Arabs, because to them partition would mean that “Palestinians who fall in what would become the Jewish state would be suddenly aliens in their own land,” explains Tufts University senior lecturer Thomas Abowd.

When Britain officially withdrew in May 1948, the independent state of Israel was declared with David Ben-Gurion as prime minister.

“It was a very emotional moment for many,” says Michael Brenner, Director of the Center for Israel Studies at American University. But “there was no time, or no opportunity, of reflection. On May 15, five Arab states declared war against Israel.”

“For Israelis,” Brenner continues, “it’s the War of Independence. It’s a kind of triumphant naming. For the Palestinians, it’s not; it’s their catastrophe. It’s their real defeat.”

An armistice agreement was reached in 1949, with the territory now known as the West Bank coming under Jordanian rule, while the Gaza Strip fell under Egyptian control.

Roughly 750,000 Palestinians were displaced, prompting the UN to launch a Palestinian refugee relief agency.

And Jerusalem? It became “a Berlin-like divided city,” describes Daniel Seidemann, a Jerusalem-based attorney, in the series.

1967: The Six-Day War

Tightly wound tensions erupted again almost two decades into Israel’s statehood as a series of escalating confrontations led to the Six-Day War of 1967.

Fought predominantly between Israel and Egypt, Jordan and Syria, the war saw the young state of Israel increase its territory as it took control over Jerusalem’s Old City along with the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and the Sinai Peninsula.

The latter was returned to Egypt under the 1979 peace agreement, and you can read more about the reality in Jerusalem today here.