Keziah Ridgeway says she’s the only teacher she knows in Philadelphia who teaches critical race theory in public high school – and she teaches it in her anthropology class, as one framework among many to understand human cultures. But she also teaches African American history, and that’s what she thinks the frenzy over critical race theory (CRT) is really about.

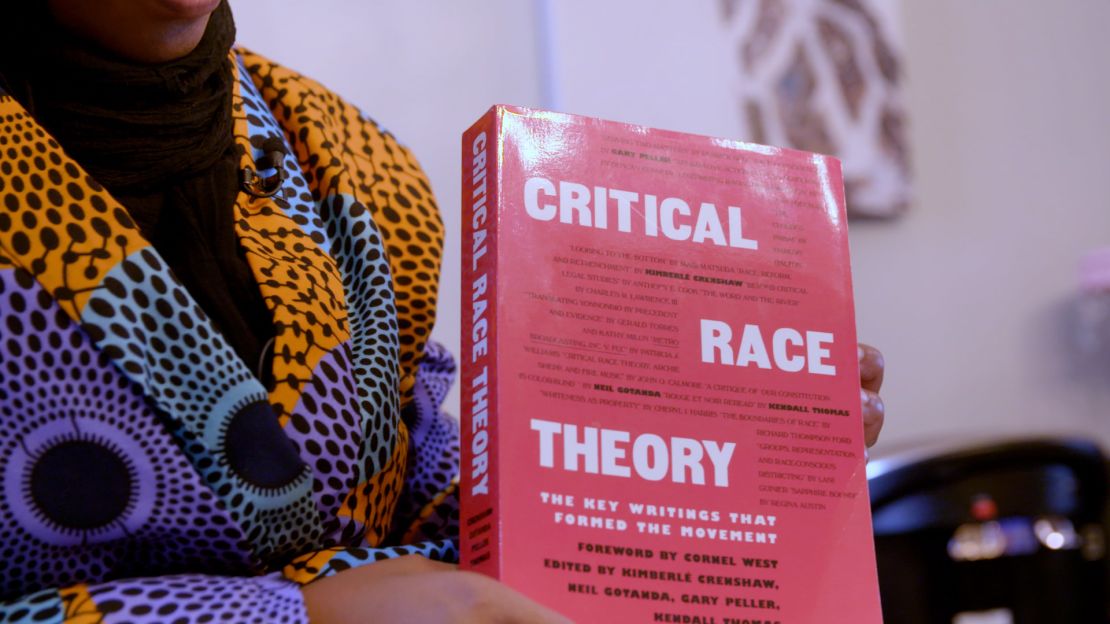

“Critical race theory is a lens, right? It’s not being taught in schools,” Ridgeway says. It’s a theory for understanding the interaction of race and the law, and is mostly taught in graduate school, not elementary school. But conservatives are using the phrase to mean any instruction about the role of race in America, past or present.

The explicit message is that such instruction puts White people in danger of being blamed for their ancestors’ crimes. Its undercurrent is that it could bring attention to the ways that White people today continue to benefit from racism.

“Can (CRT) influence the way that some teachers teach? Yeah,” Ridgeway says. “But that’s a good thing, right? Because race and racism are literally the building blocks of this country. So how can you not talk about it?”

In the wake of protests over the murder of George Floyd, Republican politicians have been hyping “critical race theory” as a threat to the impressionable minds of America’s children. In more than a dozen states, legislators have proposed bills to ban CRT. In May, Oklahoma teachers were banned from teaching that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive.” On September 1, a Texas law goes into effect that bans teaching that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to, the authentic founding principles of the United States.”

Ridgeway teaches at an inner-city school where a majority of students are people of color. She says the strongest reaction she gets from kids who take her class is that they feel like they’ve been lied to by a feel-good version of American history.

“I love primary sources, which is what I use a lot in my classroom. Because if a parent comes and says, ‘Why are you teaching my kid that Christopher Columbus was a murderer?’ I’ll just be like, I technically didn’t teach them anything. They read his diary.”

Ominous warnings about the danger of CRT have been circulating from 4chan to Fox News for a year. In the last few months, it has started turning people out. Across the country, school board meetings have gotten heated as parents have protested CRT. Last week, CNN toured the mid-Atlantic to survey the CRT discourse, interviewing Ridgeway in Philadelphia, watching a suburban school board meeting, talking to an anti-CRT activist in Pennsylvania, and watching a local Republican panel at a diner near Baltimore.

‘A conflation of issues’

This CNN crew dropped by a school board meeting in Phoenixville, in the suburbs of Philadelphia, to see if someone might show up to talk about CRT. Two did.

“We do not want our children to be taught that they are oppressed or they are oppressors by virtue of their color,” a White woman said as she addressed the school board, her kids at her side. “These are my babies. Not yours. If you are embarrassed or ashamed of your skin color, that’s your issue. Not mine or my children.” Half a dozen people clapped.

She went on to address the subject of history. “Saying America is wholly racist, and White supremacy are the biggest threats to America, is like saying Big Foot is the biggest threat. It’s a lie. 600,000 people died in the Civil War to end racism and slavery. Don’t rewrite factual history or indoctrinate. Just present the facts, not storytelling.” (She later declined to comment, saying, “I don’t like your show.”)

A White man in a suit said, “We did not want our children to be taught that America is systemically racist.” (Once the meeting moved on to less nationally relevant matters, CNN waited outside to ask him about his comments. He stood in the window and took a picture of the crew, but when the meeting ended, he left through another exit.)

These comments did not go without pushback. “What I’m hearing in these comments is really disturbing on a lot of levels,” school board member Christopher Caltagirone said. “I heard a comment that we ended racism with the Civil War.” He sounded astonished. “I’m sick and tired of seeing people try to run roughshod over the education system.”

After the meeting, some teachers and school board members lingered. A couple of teachers said they’d heard the CRT backlash was big in a nearby suburb, Downingtown. Phoenixville had gotten a few comments over the last several weeks, Caltagirone told CNN, but “I wouldn’t say it’s a majority, and I wouldn’t say we’ve been inundated.” He said he’d never seen CRT in the curriculum. “I have no clue what triggered it locally. But I think it’s part of the larger movement that we’re seeing nationally.”

“I think it’s a knee-jerk reaction to what’s gone on in society over the last year,” Caltagirone said. “It’s a conflation of issues” – history, critical race theory, equity, diversity and inclusion – “it’s all being put together. And I don’t think that’s fair.”

The idea that CRT is being used to teach young White children to hate themselves for being White has circulated in conservative media. In April, Idaho lawmakers debated a bill later signed by the governor that stated critical race theory would “exacerbate and inflame divisions” and banned public schools from teaching that individual people “are inherently responsible for actions committed in the past by other members of the same sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin.”

During this debate, Idaho state Rep. Heather Scott relayed the claims of a substitute teacher, who said students had been instructed to read the book To Kill a Mockingbird. Scott recounted, “She said the message was clear: White people are bad, Black people are innocent victims. And the students were encouraged to believe there was an endless era of Black victimization.” (To Kill a Mockingbird was published in 1960, has long been considered a literary classic, and its protagonists are a White lawyer and his precocious daughter.)

Ridgeway seemed somewhat amused but mostly exasperated by these claims. Is she teaching children to hate America? “No, I’m teaching children to question America. And that’s what makes a good patriot.” Is she teaching White kids to hate themselves for being White? “No.” Is she teaching Black kids that there’s nothing they can do to improve their situation? “Absolutely not.” Because racism exists and they can never fight it, so they should give up? “Absolutely not. I’m creating little free thinkers and resistors and future politicians and lawyers and teachers and change-makers.”

Ridgeway said she thought Pennsylvania’s governor would veto any anti-CRT bill the state legislature might pass. (When asked for comment, a spokeswoman for Gov. Tom Wolf said, “These proposals are harmful political props meant solely to stir up outrage,” but did not say whether Wolf would veto.) But even if one such bill became law in her state, she would not change the way she teaches. “I could lose my job. Is that gonna stop me from teaching the truth? Absolutely not.”

But, Ridgeway said, “I’m concerned about teachers who live in states where they have a Republican governor who is hell-bent on putting these things into law. They could be fined. They could lose their job. They could be suspended. And I think that is so problematic. Can you imagine in Germany, them banning teaching about the Holocaust?”

Parents fight ‘indoctrination’ at school

With just two days left in the2020 school year, Elana Fishbein says she received an email from her kids’ school near Philadelphia saying they would be given lessons about the role of race in American society. She said she reviewed the materials and determined they were racist.

While there are some bigots, Fishbein allowed, “American society is not racist.” She continued, “Taking a wide brush and painting this country as systemic racist, as, you know, structurally racist – it’s insane.”

She was particularly upset by the book, A Kids Book About Racism, by Jelani Memory, published in 2019. In the book, Memory says he has a Black dad and a White mom, which makes him mixed – “or African American, biracial, Black, or a person of color.” This offended Fishbein. “There’s no mention of the fact that his mother was White,” she said. “The White option doesn’t exist there. He can be Black, but he cannot be White.”

The legacy of America’s “one-drop rule” has meant a biracial person with a Black ancestor is usually considered Black. Fishbein did not find this persuasive. She said, “But the fact that somebody defines you, doesn’t make you what they define you. The fact that somebody calls me a racist, doesn’t make me a racist.”

Fishbein says she then wrote a letter to the school board and posted it on the school’s Facebook page, where she was “literally lynched.” CNN suggested perhaps she was just figuratively lynched. “Of course, of course,” she said, “very harshly, obviously, calling me racist and bigot and demanding that my post would be removed.” She said the post was deleted, and removed from other local school-related Facebook pages, too. “That’s when I started really being concerned.”

Fishbein put her kids in private school. But her interest in the public school curriculum continued.

In August, Fishbein created an advocacy group called No Left Turn in Education. Despite the name, she said, “Our goal is to get any kind of indoctrination, any kind of politicization, from our schools. It’s not about right and left. It’s about right and wrong.” An appearance on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show had generated a wave of interest, she said, though she would not say how many people had joined or how much money she’d raised.

Though her kids are out of public school now, Fishbein said she didn’t want her money, as a taxpayer, “to go to indoctrinate kids that then are going to hate my kids because of the color of their skin, and attack them because of the color of their skin, and blame them that whatever achievement they have, it’s because of the color of the skin.”

Asked if she was afraid her children would be attacked by Black children, Fishbein said, “No, I didn’t say by Black children.” When asked who exactly she feared would attack her children, Fishbein said, “What happened in the summer, it twisted the minds of all kids, all kids. My kids can be attacked by antifa kids or BLM kids that are not Black. They’re White like my kids. But they’re believing – they were indoctrinated. And they internalize this philosophy.”

Asked if her children had been beaten up by “antifa kids,” Fishbein said, “It’s going to happen if we are not going to stop it. But we are going to stop it.”

When did race stop mattering?

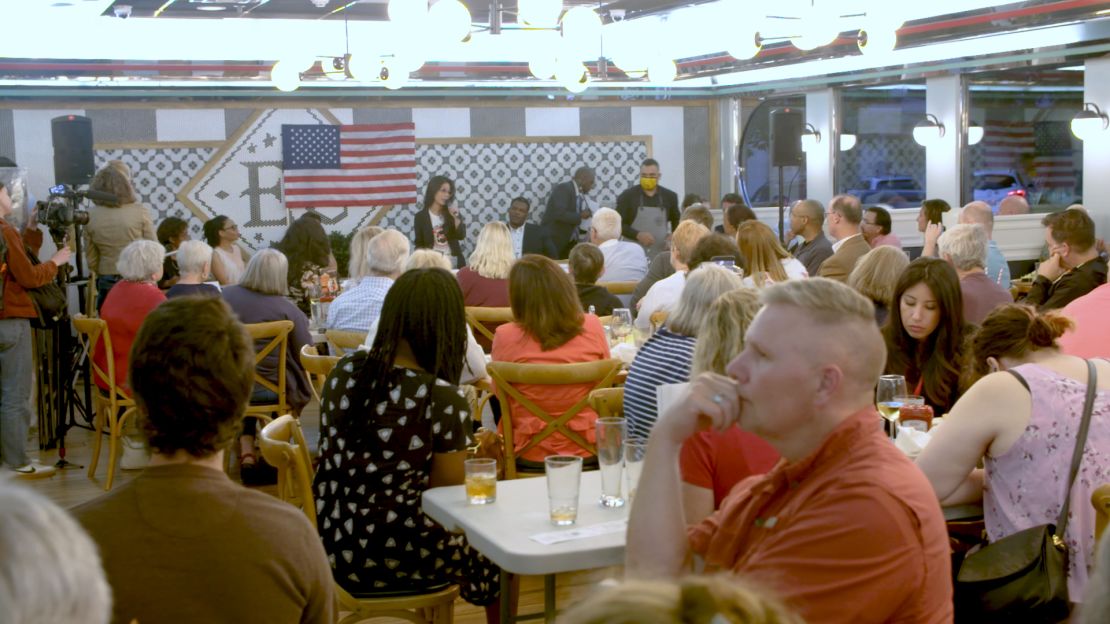

Near Baltimore, the Howard County Young Republicans rented out half a diner for a panel discussing two topics: schools being shut down amid Covid-19, and critical race theory. It was standing room only, with more than 100 people. The speakers were people of color, and the audience was mostly White. It erupted in applause as the speakers denounced CRT.

Maria Vismale, who is Black, said Black people “absolutely” have more opportunities than White people now, citing college scholarships for people of color and corporate diversity initiatives. She said of the corporate world, “If I can compete, if I am able to do the job, then they’re going to choose me over a White woman, and definitely a White male, because they’re looking for these people to diversify.”

A recurring theme among conservatives CNN spoke to was their perception that the concept of systemic racism implies individual Black people don’t have a shot at becoming rich and successful. “Telling people they can’t compete based off skin color does nothing but keep them down,” Vismale said. “Rather than tell them they can accomplish anything, like my parents did. Like I’m sure Barack Obama’s parents did, like I’m sure so many of the entrepreneurs (did).”

The real problem, Vismale said, was the education system. Vismale’s long conversation with CNN at times went in circles about whether an education system that was disadvantageous for poor Black kids counted as systemic racism.

“In Baltimore City, students can’t read and write,” she said. “And to say the issue is because of their skin color is absolutely ridiculous. It’s not because of their skin color. It’s because they don’t have the resources.” But why didn’t they have the resources? “It’s because they have been born into poverty.” But why do they have to go to poor-performing schools? Vismale said it was because school administrators were overpaid, and teachers were underpaid.

The inner-city schools weren’t working, so even if a Black kid is valedictorian, she said, “Realistically, can you compete with your counterparts who clearly have had better circumstances and schools, better input from parents, better local government, politicians, administrators that are not, basically, … being corrupt? … Yes, he can do anything. Yes, it will be more difficult for him to do it. But it’s not because, ‘OK, this man is a Black man.’ It’s because of the circumstance in which the school system was constructed.”

Schools are funded with property taxes, which means schools in poor neighborhoods have less funding, and on top of that, redlining had restricted where Black people could live – did that not all add up to systemic racism? Vismale said no.

The diner event drew all kinds, from college kids to senior citizens. There was a contingent of College Republicans from Towson University. One of them, Craig Lewis, admitted he was “not that knowledgeable” about critical race theory. “But it sounds as if – obviously, this is more of an educated assumption – that it is, obviously, teaching people, kids about race and racial issues in America’s past is very important. I was taught about slavery, Jim Crow, the whole of the history of the United States. But to paint the country as an inherently racist country from its founding, I think is dangerous. And false.”

When Lewis was reminded that the Constitution’s Three-fifths Compromise says slaves shall be counted as 60% of a person, he said, “Of course, and that was applied at an earlier time. That’s not the case now, obviously.” Asked to square the inclusion of explicitly unequal treatment in the founding documents of America with his claim that America was founded on the principle of equality, Lewis said, “Well yeah. … It wasn’t perfectly written in the Constitution. But the founding of the United States is so that all people under God are created equal.”

After watching Lewis’s interview, his buddy, Sam Jones, the president of Towson College Republicans, wanted a go. “Critical race theory is the idea that’s taught to our nation’s youth that the way that you’re born contributes to the amount of success that you can achieve in this country,” Jones said. “Basically, it states that White people are born with everything. And if you’re not White, you’re born with nothing. And you have a strategic disadvantage in making money and gaining success here.”

Jones said he had not read any critical race theory books. He could not name any critical race theory scholars. He could not name any critical race theory concepts. Even so, “I think I’ve summarized critical race theory as a whole pretty well.”

“My point is, it doesn’t matter what race you are, it matters how hard you work,” Jones said. “I think it has much more to do with the choices you make and the place you live, the people that you surround yourself with, than the color of your skin when you’re born.”

Did race ever matter in American history? Jones said yes. Race mattered a lot during slavery. Jim Crow, too. When did race stop mattering? “I mean, I’m not gonna be able to tell you an exact date of when it stopped mattering,” Jones said.

But could he give a date range? “I mean, it doesn’t notmatter. It definitely matters because there’s an implicit bias in all of us. But my point is that the success, the economic, the personal success that you’re going to make in this life has nothing to do with the color of your skin.” Could he give a decade when that became true? “Probably the 90s.”

But what specifically? “Living your life.” So in the 90s, Black people were living their lives? “Cut that one off,” Jones said and walked off-camera and out of the interview.

“Our kids are smart, they know what’s happening,” Ridgeway said. “We do them a disservice by continuing to pretend like critical race theory is the issue. When it’s really you just don’t want kids to learn the truth. Because not only do they become critical thinkers, but they also become voters.”

The people who have something to fear, she said, were the politicians. “As this generation gets older, a lot of the people who are making these laws will be voted out of office.”