Editor’s Note: Nicole Hemmer is an associate research scholar at Columbia University with the Obama Presidency Oral History Project and the author of “Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics.” She co-hosts the history podcasts “Past Present” and “This Day in Esoteric Political History” and is co-producer of the new podcast “Welcome To Your Fantasy.” The views expressed in this commentary are those of the author. View more opinion articles on CNN.

During the insurrection in January, a rioter hoisted a Confederate flag over his shoulder, letting it furl out behind him as he marched through the Capitol. It was an outrageous sight: not even during the Civil War had insurrectionists breached the halls of Congress with the battle flag. Yet there it was, flapping alongside Trump flags and America First flags as rioters – and some Republicans in Congress – tried to stop the certification of the presidential election

While the Confederate flag in the Capitol may have been staggering, it also was not out of place in a building boasting statues of men who served in the Confederacy – including Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Vice President Alexander Stephens – and defended the causes of slavery, segregation and White supremacy, including US Vice President John Calhoun and others.

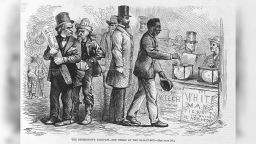

On Tuesday, the House passed bipartisan legislation that would not only remove those statues but also the bust of Roger B. Taney, the chief justice of the Supreme Court who wrote the infamous decision in the 1857 Dred Scott case, in which he declared that no Black person, free or enslaved, could be a citizen of the United States. The bill details that Taney’s bust would be replaced with one of Thurgood Marshall, the first Black Supreme Court justice. A similar measure passed the House last year but stalled in the Senate; with Democrats in a slim majority now in the Senate, the measure’s chances are far better.

One of the 120 Republicans who voted against it, Wisconsin Rep. Glenn Grothman said he opposed it because of Marshall’s support for Roe v. Wade. Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene called the move a “power grab” and Montana Republican Rosendale said, “Make no mistake, those who won the West and George Washington are next.” GOP leaders Steve Scalise and Kevin McCarthy voted for the bill, but McCarthy engaged the canard of “critical race theory” and claimed, “All of the statues being removed by this bill are statues of Democrats.”

All this demonstrates that while this was a bill passed with some bipartisan support, the broader issues undergirding the debate are far from settled. Much of the debate over Confederate statues in any public space revolves around history: what the statues meant when they were erected, often decades after the Civil War, and what story they tell about the nation’s past.

But in this case, the debate also has to be about what these objects mean in the present, what they signal to people walking through the halls of Congress to testify before congressional committees or appeal to their representatives or simply try to learn about civic life and political power in the US. The still-standing statues to heroes of White supremacy tell us less about the 19th-century than they do about the 21st. They are not just lessons about the past but potent political symbols in the present – which is precisely why they need to be removed.

The presence of Confederate symbols in government spaces has been an important part of the recent battle over statues, flags and names. That battle, long active locally and regionally, moved to the center of national debate in 2015, when a White supremacist murdered nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina. (Rep. James Clyburn of that state, also the home of segregationist John C. Calhoun, argued Tuesday that these statues should be “relegated to the dustbin of history.”)

After the massacre, debate focused on the Confederate battle flag, in part because of a widely-circulated photograph of the killer with a gun in one hand and a Confederate flag in the other. In the days that followed, activist Bree Newsome scaled the flagpole on the grounds of the South Caroline State House and ripped down the flag, and a few weeks after that, the legislature voted to move the flag to a nearby museum.

In Charlottesville, Virginia, two years later, Confederate statues became the focal point of both White supremacists and anti-racist activists. And while much important work was done on the historical nature of Charlottesville’s Confederate statues – erected in the 1920s on a hill overlooking the Black section of town, which would later be razed under the guise of “urban renewal” – just as important was the activism around the present meaning of the statues.

One effort, the Kudzu Project, which gained traction after the White-power violence in Charlottesville, drew attention to the presence of Confederate statues at courthouses across Virginia. As part of a guerrilla art project started by Margo Smith, participants protested by draping knitted blankets of kudzu, the invasive plant common in the South, over Confederate statues.

The activists contended that the placement of statues in front of courthouses was particularly noxious, because according to the project’s web site, “it valorizes the racist ideology of the Confederacy and undermines the principle of equal justice under the law.” A Black person pursuing justice at the courthouse might think twice about what kind of justice is in reach when the grounds are littered with symbols of the Confederacy, Smith argued when I interviewed her in 2018 about her project.

The Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, which the city only recently gained the ability to remove after a protracted effort in the courts, was erected to reinforce Jim Crow segregation in the 1920s. But in recent years it was reconsecrated to the White power movement that used it as a rallying point for their violent assault on the city. As such, it is not just a marker of the crimes and wrongs of the past; it is a monument to the racist violence of the present as well.

The statues in the Capitol must be understood that way, too: as markers of a racist past and as embodiments – through their continued presence in our halls of government – of a racist present.

That is why it rings so hollow when people argue that removing statues erases history. The problem is not just that most statues impart incomplete or wrongheaded history lessons. It’s that they also signal something about the present. What is too often overlooked in these debates is that leaving a statue up is as much a political statement as taking a statue down. Inaction may be a stealthy political weapon, but it is also one of the most powerful ones available.

It’s no mistake that the debate over their removal reemerged after the murder of George Floyd by a White police officer, and again after the Confederate flag breached the Capitol with an anti-democratic mob. But they also bear witness to a politics that continues to operate on the floor of Congress: from the Republican efforts to overturn the 2020 election, to the refusal to consider the voting rights and police reform legislation passed by the House, to the efforts to block investigations into the insurrection (which Nancy Pelosi has just salvaged with the creation of a select committee in the House). The removal of these statues is an important symbolic step, but one that reminds us of the need for real and meaningful reform.