Editor’s Note: Sonia Pruitt is a retired Montgomery County, Maryland police captain. She is on the Board of Directors and a speaker with the Law Enforcement Action Partnership, which advocates for criminal justice and drug policy reform and is the founder of The Black Police Experience, which promotes the education and history of the intersection of law enforcement and the Black community. She is also an assistant professor of Criminal Justice at Montgomery College in Maryland. The opinions expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion at CNN.

Congress is now in recess, and only has a “framework” for a police reform bill from the Senate. Since early March, there have been negotiations but no decisive action on the Justice in Policing Act (JPA) that bears George Floyd’s name. Floyd died at the knee of Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020, which ignited a firestorm of protests around the world due to the excessive force and abuse of power that led to another unnecessary death of a Black man, and a murder conviction for Chauvin. It brought to the fore the never-sleeping giant of racial discord that has divided the Black community and law enforcement for hundreds of years.

I wonder how George Floyd would feel, knowing that there is just a framework for the JPA, more than a year after his death? What is the hesitance to make difficult but appropriate decisions for crucial changes in police culture that would undoubtedly save lives?

The purpose of the bill is stated as: “To hold law enforcement accountable for misconduct in court, improve transparency through data collection, and reform police training and policies.” Yet, the portions of the bill that could best address these objectives seem to be the ones which the Senate is having the most difficulty with.

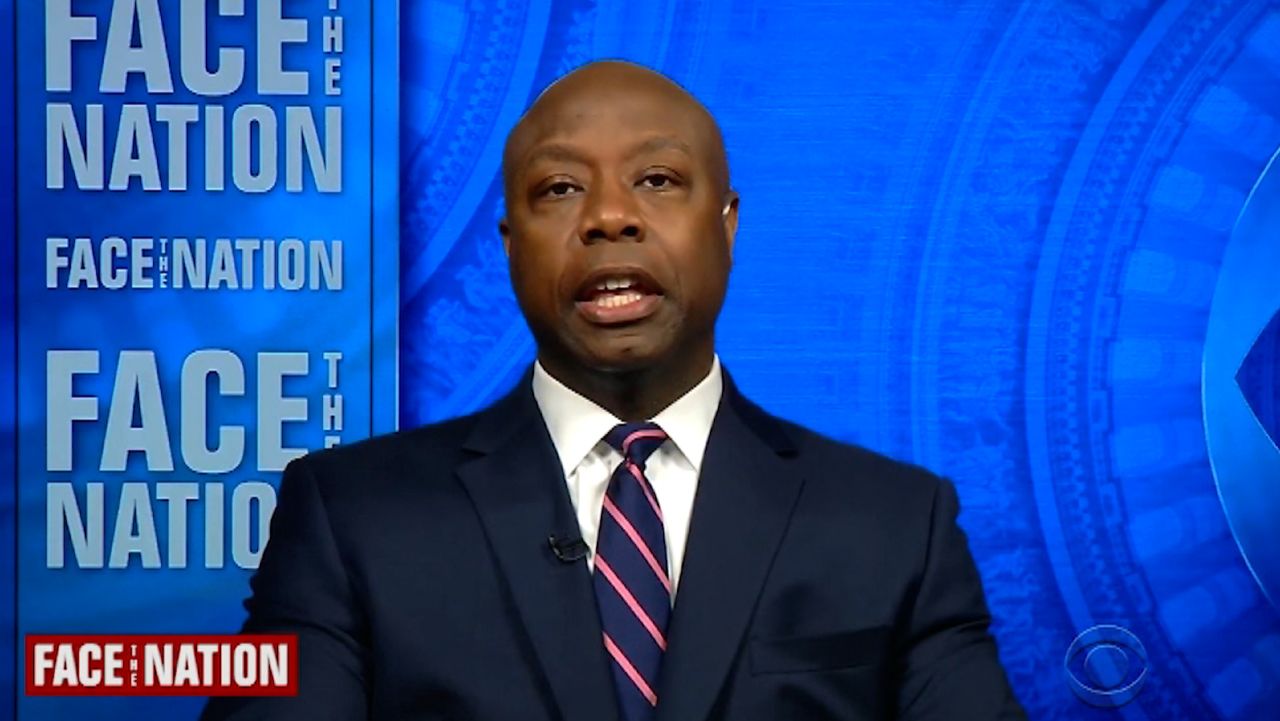

Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina has stated, “…we just need to agree on the actual language we’re using.” I also believe that the nuance of language is important. However, as lawmakers are struggling to find the right words, I hope they understand that the most significant goals should concern strong restrictions on use of force, police misconduct and the complete elimination of qualified immunity.

Police unions and other traditional police organizations have had great success lobbying the Hill, while Black and other less conventional police organizations that support impactful police reform have had minimal input. As a result, GOP allies of police unions are reticent to support legislation that would make the process easier to place criminal charges on police officers for excessive force. Further, both unions and GOP allies are wholeheartedly against the elimination of the legal doctrine of qualified immunity, which protects police officers from civil liabilities.

Historically, traditional police groups have stood solidly behind the most extreme police protections, even when those protections were not in the best interests of the people they serve. In addition, there is a narrative that officers are leaving policing because the community does not respect them. It is true that officers are feeling unbalanced. The shaking under their feet, however, is not community dislike—it is accountability for police abuses coming to bear.

The public has pulled back the curtain on the “Blue Wizard of Oz” and discovered what they already knew before the death of George Floyd – that not everything is right and true in policing. The strong police pushback in the face of formidable public distrust feeds the hesitancy to do what is ultimately the right thing in holding the police accountable.

The seemingly most controversial issue of police reform – qualified immunity – is not codified. It is a doctrine that has protected police officers from civil liability for decades. Thus, it does not need reform as a law would, and could easily be eliminated, as it should be. Any doctrine that gives more power to the police than to the people has been proven to have no place in police accountability. Sen. Scott supports the idea of police departments facing civil liability rather than individual officers. This is not a viable option, as it does not give officers incentive to avoid unethical and unlawful behavior, and local governments already bear the brunt of civil lawsuits from disaffected citizens, paying out millions each year in taxpayer dollars.

Republicans in the Senate feel that eradicating qualified immunity would result in an increase in frivolous lawsuits against officers. However, protections currently exist for officers through the Constitution, and a review of all potential civil cases by the courts already eliminates such lawsuits from moving forward. Finally, opponents of strict police reform suggest that the conviction of Chauvin on murder charges is proof that the current criminal system can be just – but one conviction and a 22.5-year sentence does not mean wholescale change in policing.

As lawmakers negotiate the terms of the bill, I hope that they keep in mind the overarching issues that brought us to this place – equity and safety for Black and other vulnerable communities. Like any other good business or political venture, you are only successful if the people you serve have buy-in on what justice and safety looks like. The community has spoken – the expectation is a strong bill that protects the community. Diluting and delaying accountability would only leave America empty-handed in the search for justice.