It was only last year when Hannah Lindell-Smith woke up in the middle of the night with the taste of smoke in her mouth. The orange sky over Washington and Oregon was filled with embers as wildfires raged, leading to some of the region’s most prolonged and dangerous air quality crisis.

As smoke poured into their Seattle home that night, the teen helped her mother fill every crack and crevice with towels and sheets — whatever they could find — to keep it out.

Now the 15-year-old is about to experience yet another record-breaking weather event, one that not even her mother has experienced in her lifetime.

By late weekend, vast swaths of Washington and Oregon will roast in temperatures 20 to 30 degrees above what’s normal for this time of year. The National Weather Service in Spokane warned Friday it will be “one of the most extreme and prolonged heat waves” in Northwest history.

“I’m worried about how [Seattle] is going to handle this,” Lindell-Smith told CNN. “It’s scary seeing what the world is going to look like. This is clearly evidence that our climate is changing.”

Extreme heat is one of the most pernicious consequences of human-caused climate change, killing more people each year on average than any other weather-related event. Climate change is also going to make record-breaking heat waves more frequent in the future — something researchers and policy experts say the Pacific Northwest is not prepared for.

Seattle and Portland rank first and third, respectively, among cities with the highest proportion of households without air conditioning, according to a US Census Bureau survey of 25 major metropolitan areas. And, experts say, those least likely to have air conditioning are the people who will endure the worst heat — historically underserved communities of color, the elderly, the houseless and low-income residents living in so-called urban heat islands.

“Unfortunately we’re not well-prepared, generally speaking in the Pacific Northwest, for heat,” Vivek Shandas, a professor of climate adaptation and urban policy at Portland State University, told CNN. “Our [power] grids are largely taxed during the wintertime for heating purposes, but in the summer, there’s a lot less capacity in the grid to be able to actually manage some of the major drains on cooling infrastructure that’s needed.”

Rep. Earl Blumenauer of Oregon, who has been outspoken on the climate crisis, says extreme heat is one of the region’s weak spots.

“We had a preview last summer with the horrific wildfires and heat, and now it’s coming with a vengeance as we look at three days potentially over 106 degrees [in Portland],” Blumenauer told CNN. “Heat at this level is something that will kill people and will get lethal very quickly.”

When a wicked winter storm and days of bitter cold pushed the Texas power grid to its breaking point, experts warned that other states and grid operators should also prepare for atypical weather that could become more common in a changing climate.

Similarly, the Pacific Northwest now needs to adapt to heat, experts say. This weekend is likely just a curtain-raiser for what’s to come as climate change makes these events — which used to be outliers — worse and more frequent.

Black and brown neighborhoods will disproportionately suffer the most from the warming trend, compared to their White counterparts, according to a 2019 study, on which Shandas was a coauthor, which examined the history of segregation and disinvestment in communities of color.

Low-income residents and communities of color tend to be in areas that lack tree cover, green spaces and access to cooling centers. Many work blue-collar jobs, where they are exposed to heat for long hours, to pay rent for apartments that don’t have proper cooling systems, Shandas said. And some of these vulnerable communities also tend to live in multi-generational homes or apartments, where crowding makes the heat feel even worse.

Air-conditioning in the West and Northwest is less common than anywhere else in the United States, according to survey results from the US Census Bureau, and can be unaffordable for low-income residents. About 56% of Seattle-area homes, for instance, do not have air-conditioning units.

Shandas, who lives in Portland, said he only just bought an air conditioning unit for his family last week.

“We don’t have a history of having long stretches of heat days,” he said. “And whether people are recognizing that they’re actually experiencing some level of heat stress, it might be an unfamiliar experience for them.”

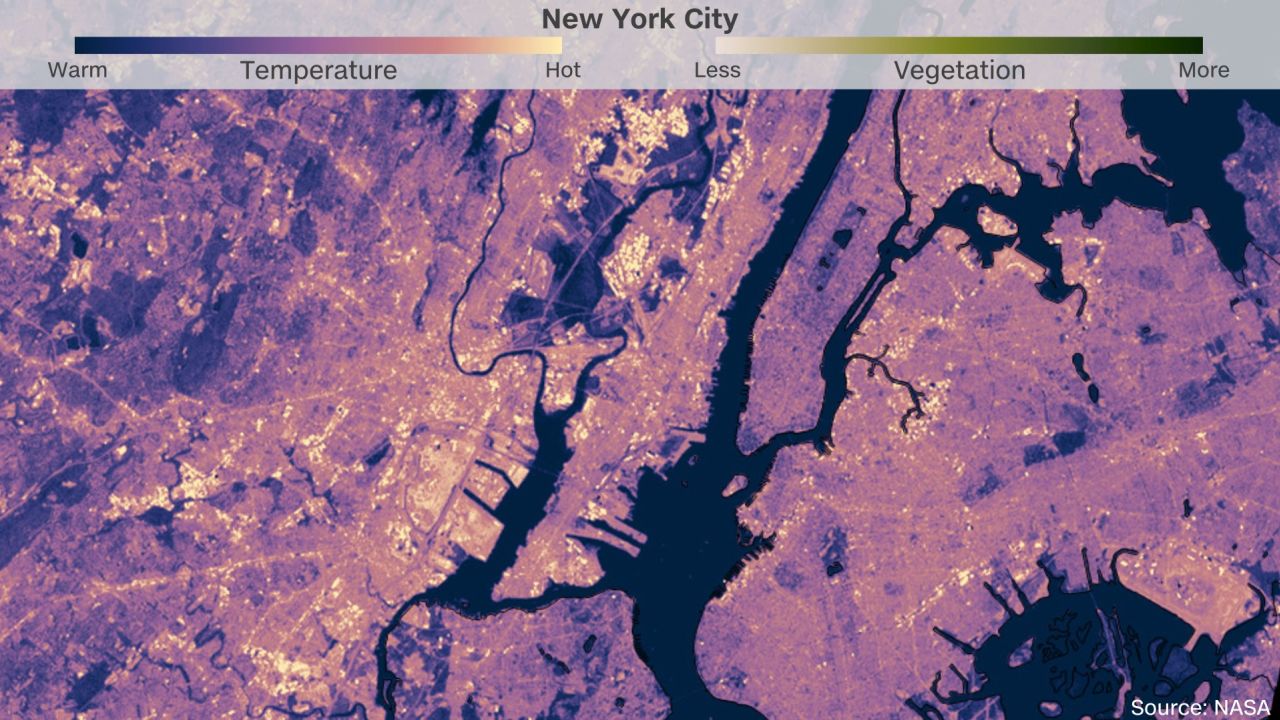

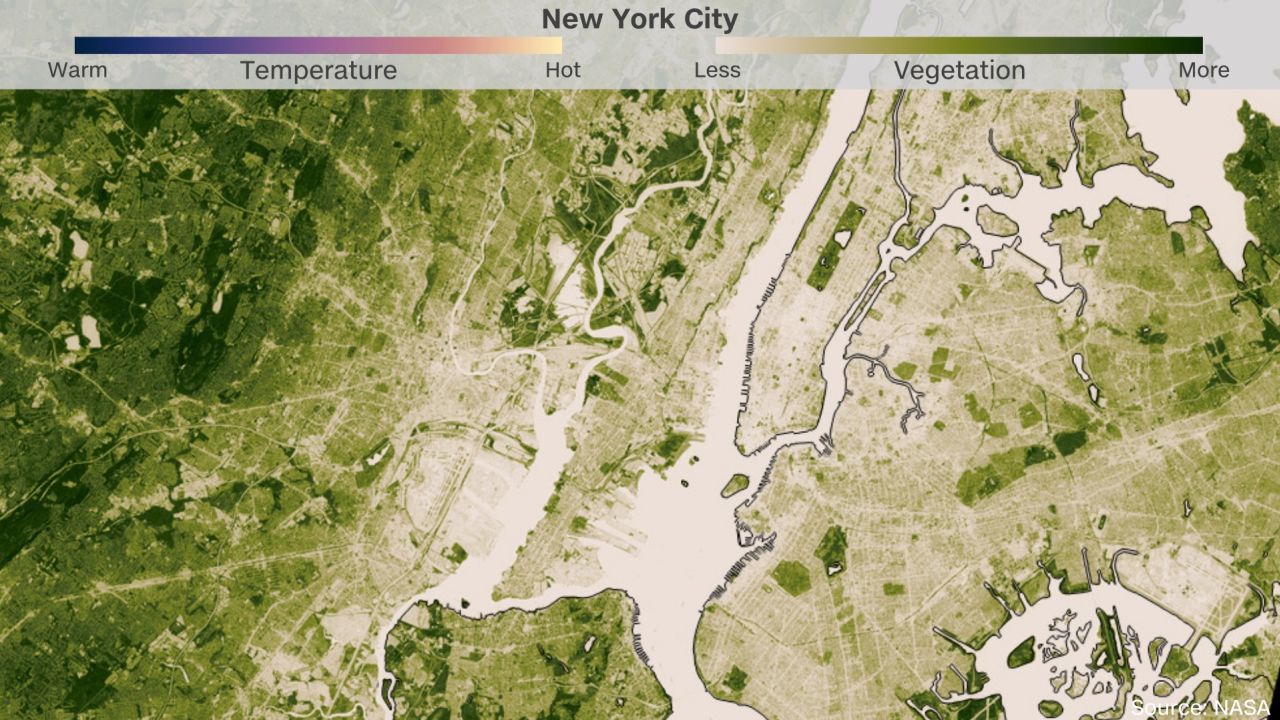

The urban heat island effect compounds these issues. Areas with a lot of asphalt, buildings and freeways tend to absorb a significant amount of the sun’s energy and emit it as heat. Areas with green space — parks, rivers, tree-lined streets — absorb and emit less.

In his 2019 study, Shandas found that the hottest areas within city limits were low-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color, places that historically have enjoyed the least improvement and investment. These are neighborhoods slotted next to traffic-choked freeways, where you can walk blocks without seeing trees, let alone a park.

Meanwhile, more affluent neighborhoods, which have more green spaces, are cooler.

“We’re seeing this intra-urban variation, where one street has a 15- or 20-degree difference from streets that are just less than a mile away,” Shandas said.

That kind of temperature differential could put some neighborhoods in a deadly situation, especially for a region that emergency managers say is not acclimated to extreme heat. Since the mid-1970s, Seattle had an average of three or four heat-related deaths each summer. During a sweltering summer in 1992, the number jumped up to 50 to 60 deaths, according to the Seattle office of emergency management.

Deepti Singh, a climate scientist at Washington State University at Vancouver, said the lack of investment in low-income areas affects their ability to cope with extreme weather events.

“Investing in resources to help these communities is real important, because they have less ability to escape to cooler areas because it’s not economically feasible for them,” Singh said.

City officials are taking steps to keep residents safe this weekend.

“It’s uncommon to have potentially three days above 100 degrees, but it’s certainly not our first heatwave where we’ve had to take additional action,” Dan Douthit, spokesperson for the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management, told CNN.

Douthit said cooling centers will be open through the weekend during peak heat hours, and if residents need transportation to get to cooling centers, the city will provide a ride.

Seattle city officials are urging residents to seek refuge in more than 30 cooling centers it plans to open, which include senior centers, community centers, libraries, and an emergency shelter as well as beaches, pools, and spray parks.

Blumenauer says that as summers get warmer, people in the Northwest are in for a wake-up call — all the more reason, he said, that climate resiliency plans should be included in the infrastructure package Congress passes.

“We’re not ready for the strain that we’re going to see in the electrical grid,” Blumenauer said. “People’s habits are going to have to change. Those who have air-conditioners are not going to be able to crank them up all the way. It’s going to pose severe strains, which means we can look at blackouts.”

But Portland General Electric said it is ready for the high demand: “There’s no doubt we are looking at hotter, drier weather here in the Pacific Northwest than has historically been the case,” Andrea Platt, spokesperson for the utility, told CNN. “The big message is that PGE is prepared for this extreme heat and high electric use.”

Julie Moore, spokesperson for Seattle City Light, told CNN the utility is expecting a little over 20% more power use than what’s normal for this time of year, but the utility and the regional partners are “confident we will ride this out.”

“We do not anticipate any proactive service outages,” Moore said, “but will be monitoring conditions and will respond appropriately if an unexpected concern arises that could be mitigated with a shift in operations.”

In addition to improving infrastructure, Singh said investing in education and preparedness programs in vulnerable communities is key.

“Cities are doing the important job of opening cooling centers, which can provide respite from the heat for many members of the community that might not have access to A/C’s,” Singh said. “Investing in these community resources for vulnerable populations is critical as well as educating the public how to be prepared during these types of extreme events.”

If the US fails to slash planet-heating emissions, people in cities like Portland and Seattle – which today can still be considered sanctuaries from extreme heat – would need to fundamentally change their way of life as temperatures continue to warm.

By the middle of this century, for example, the number of days that hit 90 degrees in the Pacific Northwest is expected to increase from a current average of around six to 16, according to a study from the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Lindell-Smith, who is still in high school, said last year’s wildfires were an awakening. She joined the Seattle chapter of the Sunrise Movement, a youth climate activist group, and started working with local climate organizations in Seattle.

“The wildfires [were] a defining moment for me, and now we have this heatwave,” said Lindell-Smith. “The climate crisis is scary, seeing what kind of world we’re going to be growing up in.”

Pedram Javaheri and Stella Chan contributed to this report.