In the year that has passed since the nation was confronted with harrowing video showing a Minneapolis police officer killing George Floyd, police and politicians across the country have been scrutinizing the failures in police leadership, culture and training that Floyd’s murder exposed as they seek to redefine policing in America.

Police leaders in major cities are incorporating lessons learned from the Floyd case into their use of force policies, such as the obligation of fellow officers to intervene in excessive force incidents, rendering first aid to those harmed by police, and holding officers accountable by their colleagues for complaints and allegations of misconduct.

But as departments face an anti-police climate, as well as calls to defund their budgets following several police killings of Black Americans, law enforcement leaders face the daunting long-term challenge of fostering a cultural change whilebuilding trust with communities even as new incidents of excessive force dominate the news cycle.

“There is an appreciation for just how fragile that trust is because the Floyd incident happened in Minneapolis yet cities across America are impacted by it,” said Charles Ramsey, former DC and Philadelphia police chief and a CNN law enforcement analyst. “It doesn’t matter any longer where an incident occurs, it’s going to affect law enforcement across the country. That realization really hit home.”

Floyd’s murder spurred one of the largest protest movements in American history, and with it came an unprecedented wave of police reform efforts that dominated local, state and federal legislative agendas.

A landmark bill in Congress called the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act passed the House in March but does not have enough votes to advance in the Senate in its current form. Bipartisan negotiators expressed new found optimism on Monday that a compromise on several key aspects of the bill is within reach.

Chauvin, who had 18 complaints filed against him before his May 25 encounter with Floyd, was found guilty of murder and manslaughter charges by a Minneapolis jury last month. The viral video taken by a bystander shows Chauvin kneeling on the neck of Floyd as he laid handcuffed and prone on the street after being apprehended for allegedly passing a $20 counterfeit bill at a corner store. Prosecutors in the trial said Chauvin knelt on the neck and back of Floyd for 9 minutes and 29 seconds.

Three other Minneapolis officers, Tou Thao, J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane, who were on the scene face state charges of aiding and abetting Floyd’s murder. The officers are set to stand state trial in March 2022. Separately, all four officers were indicted by a federal grand jury this month on civil rights violations during the arrest. The federal trial for Thao, Kueng and Lane is set to take place in August. Chauvin’s federal trial date has not yet been scheduled.

In April, the US Justice Department announced federal civil rights investigations into the practices of the Minneapolis and the Louisville police departments. The impending probe in Louisville comes just over a year after 26-year-old Breonna Taylor, an emergency medical technician, was fatally shot by officers in her apartment during a botched raid in March 2020. A grand jury indicted one of the officers on three counts of wanton endangerment — and he pleaded not guilty.

“This is a moment for a comprehensive review of the entire criminal justice system, not just police,” Ramsey said. “This is a movement, and police are the best place to start. But don’t just end it there. There’s thoughtful discussion and decision making that goes into how reform ought to look and not just a quick response to try and fix a very complex problem.”

Minneapolis has ‘to be serious’ about reform

In the wake of Floyd’s murder, members of the Minneapolis City Council announced plans to defund and “dismantle” its police department. In December, the council voted to redirect almost $8 million from the police department toward community-driven and violence prevention programs.

The Unity Community Mediation Team, a Minneapolis-based group of community activists, has been working directly with the police department in their efforts to implement necessary reforms and secure a more diverse leadership, among other recommendations, to revive public confidence in law enforcement.

“The difference now is that there’s more awareness of the atrocities that the Minneapolis Police Department has been getting away with for decades,” Pastor Ian D. Bethel of the New Beginnings Baptist Ministry told CNN. “That’s the difference.”

The group worked with the city’s police department in 2003 and negotiated a federally mediated memorandum of agreement to improve policing as a “first step in addressing the historic grievances of the communities.”

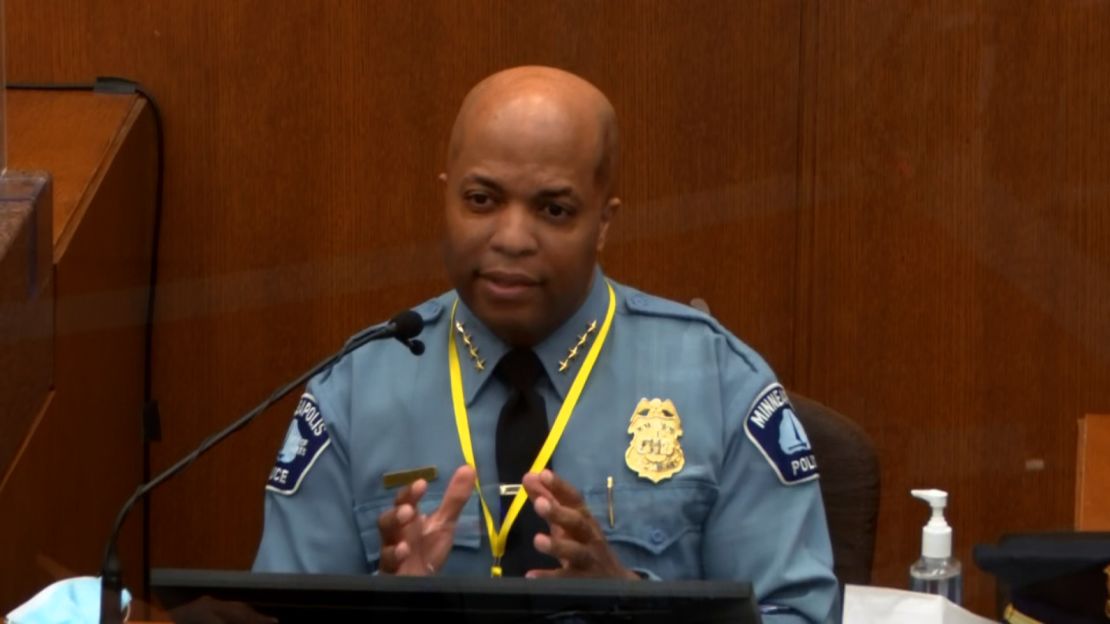

The document details a breadth of concerns pertaining to use of force policies, police and community relations, encounters between police and people experiencing mental health issues, as well as diversifying the police force. The agreement was signed by then-sergeant Medaria Arradondo, who is now the city’s police chief.

“What we’re going to do and what we are doing is to make sure we have proper law enforcement in our Black community, in our Brown communities,” Bethel said. “We have to be serious about being at the table and making some concrete decisions about reform that will last generationally.”

Minneapolis City Council President Lisa Bender and her constituents have led efforts to eliminate the police department and replace it with a new model for public safety.

“We have invested like so many cities, for years, for decades, in policing as basically the only way we’re investing in keeping people safe,” said Bender. “So people think of policing as synonymous with safety, but it isn’t working.”

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, however, is opposed to defunding the city’s police department but has prioritized changing its structure and culture, with a specific focus on building police and community relations and public safety.

“These programs need to operate as supplemental to the work that is underway already in our police department,” Frey said at a press conference this month. “You need law enforcement and the community driven approach working simultaneously to see safety.”

Frey and Chief Arradondo have announced several key changes to the department over the past year, according to a recent report, including an overhaul to its use of force policy, a new policy on “no-knock” warrants, and a new requirement to report instances of police de-escalation attempts.

More than 3,000 bills have been taken up

Many police reform efforts, such as peer intervention and de-escalation, had already been underway in recent years, but the impact of Floyd’s case only intensified the effort, according to Roberto Villase?or, former chief of the Tucson Police Department who was a member of former President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

“The public has demanded that police departments deal with things like de-escalation, active intervention and lowering the threshold intensity,” said Villase?or. “These things have been going for quite some time, but they absolutely haven’t been going with the fervency that they are now.”

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have introduced significant legislation that focuses on some aspect of police reform, with more than 3,000 bills that have been taken up by state legislatures since May 25, 2020, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). So far this year, 23 states have enacted bills that address police policies, NCSL data shows. The most prevalent themes focus on police oversight, accountability, and standards, according to the NCSL.

There are historical parallels between the events of 2020 with the period of civil unrest and riots in 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., according to Peter Moskos, a former Baltimore police officer and professor in the Department of Law, Police Science, and Criminal Justice Administration at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“It does seem like a lot of the exact same things happen for the same reason, in terms of police abuse, civil unrest, rise in violence, talk about police reform,” he said. “In that case, over decades, there was real change in policing.”

The acknowledgment that Floyd was murdered indicates a positive change in policing, Moskos said, but incremental improvements in technology and training tend to fall short in addressing the point of the debate: race, violence and police killings.

Chauvin’s trial further intensified the need for better police training with Chief Arradondo’s testimony that the former cop violated department policy and his use of force was unjustified. Many departments have implemented techniques in their training curricula that address implicit bias, de-escalation, peer intervention and critical decision making.

Agencies in Baltimore, Dallas, and New Orleans had already drafted policies that required officers to intervene in excessive use of force incidents before last summer. The Baltimore Police Department overhauled its use of force policy that included the duty to intervene and render first aid under a federal consent decree, according to Baltimore Police Commissioner Michael Harrison, who is also the president of the board at the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), a national police research and policy organization.

“We had already planned to do this before the killing of George Floyd, but even after that it just brought a heightened sense of awareness of how important that training and those policies are in the direction that our department needs to move in,” Harrison said.

On a national level, PERF has developed a police training program called Integrating Communications, Assessments, and Tactics (ICAT) that teaches officers how to “successfully and safely” de-escalate critical incidents.

Hundreds of agencies have incorporated ICAT into its training. Robin Engel, a professor of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati, evaluated the program and found a 28% drop in use of force incidents by Louisville officers.

This comes as more recent incidents of police using deadly force dominate the news cycle, including Daunte Wright, 20, in Minnesota and Adam Toledo, 13, in Illinois, have continued to erode the trust between communities and police.

The National Network for Safe Communities is a national organization that works with police departments to build trust and relationships with communities by facilitating listening sessions and engagement.

“What we look at in our framework is taking the recent cases that strengthen the need for a trust building framework with police that entails acknowledgment of harm by law enforcement leaders,” said Paul Smith, the director of reconciliation for the organization.

“Hopefully that this is a way to bring community voices into the work of public safety and a pivot away from just the militarized kind of policing that happens,” he said.

Reform efforts require investment, experts say

While efforts to defund and abolish police departments have been losing ground, reform is not, says former police chief Villase?or. But departments are already strapped for cash and have fewer officers at a time of economic collapse brought on by the pandemic, he said.

“We want to accomplish these changes and enact them, yet that causes a problem because it requires an investment from the government at a time when due to either political pressure or economic reality, they do not have the capacity or desire to invest in the proper areas of the agency,” said Villase?or. “It’s a conundrum for the departments because they are willing to change but they need people to help train the new change.”

Several cities such as Minneapolis, Austin and New York have slashed police budgets amid calls and public pressure to defund the police, but the movement has not been pervasive across major cities, according to Laura Cooper, the executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Associations. The nationwide surge in violent crime during 2020 has continued into this year, with over 7,500 people being killed by gun violence since January, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

“There has been a little bit of retooling of department budgets, but for the most part I can’t say defund has actually played out,” Cooper said. “The sustained increase in violent crime, the gun violence that we’ve been seeing and calls from the community that they don’t want less police, they want better police, seems to be resonating.”

Police chiefs are looking to hire from a more diverse pool of candidates to better reflect the communities they serve, according to Cooper, but they face significant challenges in hiring cops and keeping them in the profession due to an anti-police sentiment, the defund movement, and budget constraints.

Minneapolis saw a 20% drop in the average total number of police officers by late January of this year compared to 2019, according to city data. Chief Arradondo said the decrease in staffing levels could leave the police force one dimensional.

“Reimagining and common sense do not have to be arch enemies,” Arradondo said during a press conference this month. “We have smart people. We can get together and we can solve these issues.”

The Police Executive Research Forum did a survey with agencies in September that revealed 36% of respondents had a higher rate of resignations and retirements since June 1, 2020, compared to the same period over the five years prior.

“People in law enforcement ask how we’re going to do this when we’re losing people and we can’t get replacements,” said Villase?or. “When we do get replacements, we put them out in the field, but we can’t put the investment in training or auditing to make sure we’re doing things the way we’re supposed to.”

The development of thoughtful, effective police leadership is “critically important” in creating a better culture of policing, according to Ramsey, the CNN law enforcement analyst. “With 18,000 police departments in this country, how do you get any kind of standard and uniformity with that many agencies? Good leadership ought to be by design, not by chance.”