Editor’s Note: Anushay Hossain is a journalist and host of the Spilling Chai podcast. She is the author of the forthcoming book, “All In Your Head: How Sexism in Healthcare Kills Women.” The views expressed are her own. Read more opinion at CNN.

When I heard the news that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are recommending that the United States pause the use of Johnson & Johnson’s Covid-19 vaccine over six reported US cases of a “rare and severe” type of blood clot, I was infuriated. Pausing was the right decision, but it also immediately made me think about how sexist the medical world remains and what little regard it has for women’s health.

All six reported cases occurred among women between the ages of 18 and 48, according to a joint statement on Tuesday from Dr. Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the CDC and Dr. Peter Marks, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

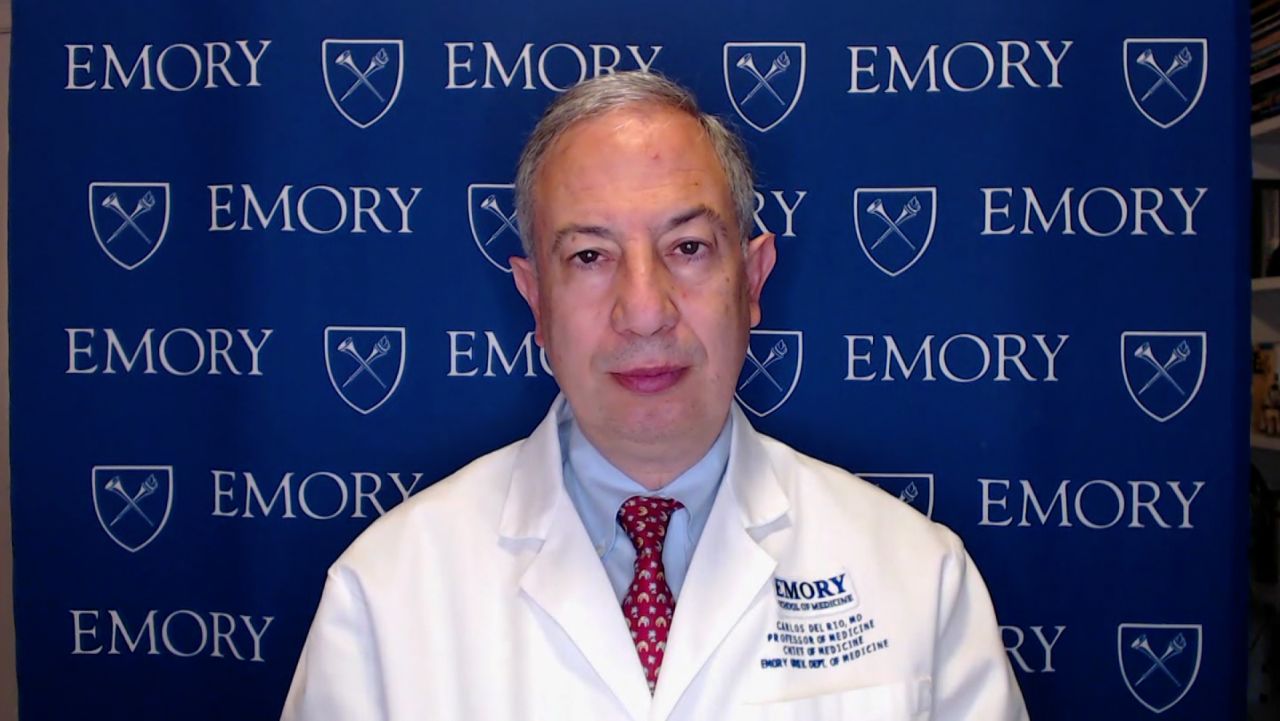

“It’s a very rare event,” Dr. Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean of the Emory University School of Medicine at Grady Health System, told CNN’s John Berman and Poppy Harlow. “You’re talking about 1 per million, and when you give millions of doses of vaccines, you will see events like this that you couldn’t see in the clinical trial just because you didn’t have millions of people enrolled.”

Dr. del Rio added that he applauds both the CDC and the FDA “for very quickly jumping on it, halting the vaccinations until we know more, and really trying to understand what’s going on.”

While I agree with him, it’s enraging in a way to consider how immediate worldwide action has been after six out of 6 million people developed clots after the J&J vaccine. This action is, among other things, a reminder of how little people seem to know or care about women’s health.

To be clear, I am not advocating against the pause on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. What I am saying is that the pause actually provides us with an important opportunity to confront how little most of us know about women’s health, despite many on the right policing and politicizing it to no end.

I’m angry because of how few people seem to realize that women who take hormonal birth control are at risk for developing blood clots, and one in one thousand will. It’s key to note that the type of clotting at issue with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is of a different type than is seen with oral contraceptives. This isn’t a direct comparison. It’s the confluence of factors here – treatment, gender, safety and messaging – that are rightly raising eyebrows at this juncture. We must ask the question: How are women supposed to have confidence in their reproductive health and medical care when there are so few acknowledgments of the risks they bear?

My upcoming book asks just that, but the truth is excluding women from testing and clinical trials is a tale as old as time in the US. Between the 1970s and 1990s, both the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and FDA, along with other regulators, had a policy that ruled out women of so-called childbearing potential from early-stage drug trials.

The NIH only began to acknowledge the widespread issue of male bias in preclinical trials in 2014, and it wasn’t until 2016 that they mandated that women must be included in studies for which research money was granted. But even with the massive gendered impact of Covid-19 unfolding in 2020, pregnant women were still not explicitly included in vaccine trials (though some people in the vaccine trials did become pregnant and research shows the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines to be effective in pregnant and lactating women).

If you’re a woman of color, things are worse for you overall – not only when it comes to the pandemic. Let us not forget that the CDC reported an increase in America’s maternal mortality ratio from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 births to 23.8 deaths per 100,000 births between 2000 and 2014, a 26.6% increase in the country’s maternal mortality rate.

More women die giving birth in America than any other industrialized country, and women of color are bearing the worst risk. Black women are 243% more likely than their White counterparts to die from preventable pregnancy-related complications.

While everything from race to income to education factors had been blamed in the past for this disparity, a Covid world has forced experts to acknowledge the role racism plays in these deaths.

Vice President Kamala Harris herself acknowledged this on Tuesday after the White House issued its first-ever presidential proclamation marking Black Maternal Health Week as part of the administration’s broader efforts to draw attention to and address the vast racial gaps in pregnancy and childbirth-related deaths and complications in the United States.

“Black women in our country are facing a maternal health crisis,” said Vice President Kamala Harris, who hosted a round table on the issue alongside Susan Rice, director of the Domestic Policy Council. “We know the primary reasons why: systemic racial inequities and implicit bias.”

While on the subject of risks posed to women’s health, can we devote more research and media attention to why some birth control does cause 1 in 1000 amongst us to develop blood clots? And while we are at it, can we also take better steps to ensure that no woman dies giving birth in the world’s richest democracy?

Blood clots and death in childbirth seem to remain just two of the risks that American women, especially women of color, are simply expected to take as a part of living our regular lives – if we want to have children, or if we want to control our reproductive destiny. This is the price we pay for being born female. We are assumed to be willing to risk paying with our health, or in some cases, our lives.

Stay up to date on the latest opinion, analysis and conversations through social media. Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion and follow us @CNNOpinion on Twitter. We welcome your ideas and comments.

For centuries, women’s pain and symptoms have so often been dismissed and written off as women being “hysterical.” The time is now for women to flip our “hysteria” complex on its head so that we get the support, information and confidence we need to be our own best health advocates.

Perhaps a little fury and confrontation is just what the doctor ordered for a much-needed revolution in women’s health care. What better time than right now?