Some conservatives who pushed and prodded for the Senate to quickly confirm Amy Coney Barrett to succeed the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court last fall are rattled by what they have seen so far.

Barrett has only been on the bench since late October, providing an exceedingly small sample size, but her votes not backing President Donald Trump in attempting to overturn the 2020 election as well as a mixed ruling in a clash between houses of worship and California have brought concern to some who heralded her nomination.

The nervousness so early in her tenure reveals more about the high hopes of the conservative movement that has finally obtained a 6-3 majority than it does about Barrett’s own jurisprudence.

“You have a lot of people in the conservative movement who are so far disappointed and a little despondent about those votes,” said Kelly Shackelford, president of the First Liberty Institute – a group dedicated to defending religious liberty.

“But I think they are reading way too much into what evidence we have so far,” he said, noting that the votes came in emergency applications and cert petitions, and not in published opinions. “Instead, we have to wait on significant opinions before we can tell where she is.”

A separate source with close ties to religious liberty groups said that he had had a similar conversation with “more than a handful of people.” “There is concern and worry,” the source said, going as far as to call Barrett “timid,” but acknowledging a “‘wait and see’ component.”

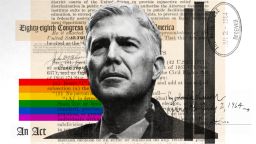

The source expressed concern that the court would end up in a 3-3-3 lineup in some cases with the liberals on one side, and Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Barrett in the middle and Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas on the far right.

Trump’s most lasting legacy will be his judicial nominations, and conservatives are impatient to see how the more than 200 judges – including three justices – he nominated to the federal bench will reshape the country.

Worries among supporters for judicial nominees or disdain for rulings that overshadow their overall record is nothing new for advocates. Roberts, for instance, has expanded 2nd Amendment rights, gutted the Voting Rights Act and has voted against same-sex marriage, but also saved Obamacare.

Last term, many conservative allies were stunned by an opinion penned by Trump nominee Gorsuch that went in favor of LGBTQ workers, although Gorsuch has cast other votes in their favor, particularly on the issue of religious freedom. They are hoping that Barrett will not surprise them in the big cases, and instead, solidify the court’s rightward tilt, fulfilling Trump’s promise to change the direction of the court.

The worst-case scenario for conservatives, of course, is that she would eventually be like Justice David Souter, the George H.W. Bush nominee who eventually joined the liberal wing. But there is nothing in Barrett’s record to indicate that would happen.

The perception of Barrett could change instantly however with a couple of key cases.

The justices have heard oral arguments in a case that could determine the future of Obamacare, as well as a significant religious liberty dispute out of Philadelphia.

Also pending is a petition concerning a Mississippi 15-week abortion ban that would be a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade. It takes four justices to agree to hear a case, and it would be a major signal of Barrett’s intentions if she indicates publicly her stance. In addition, on Friday the court is considering whether to take up a case next term concerning the scope of the Second Amendment – an issue the justices have so far declined to revisit over the past decade.

Next term could also bring cases on affirmative action and voting rights.

A Republican who worked on Barrett’s nomination on the Hill said he hasn’t heard of similar concerns among the GOP senators who were deeply satisfied with her performance during her confirmation hearings and believed by the end of the term, Barrett would vote solidly for the right side of the bench.

Despite any hand-wringing or nervousness, Barrett’s impact has already been felt on the court’s strong 6-3 conservative majority.

On the bench, Barrett voted in her first abortion-related case granting the Trump administration’s request to reinstate long-standing restrictions for patients seeking to obtain a drug used for abortions early in pregnancy, over the dissent of the three liberals.

It was Barrett who cast a key vote in a November case challenging Covid restrictions put in place by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, limiting the number of people attending religious services. Barrett sided with the conservatives in favor of the houses of worship, while Chief Justice John Roberts joined the liberals in dissent.

The vote was notable because before the death of Ginsburg, the court split 5-4 on similar cases out California and Nevada ruling in favor of the states. The majority flipped with the addition of Barrett.

The 2020 election

Those who wanted the court to weigh in on the 2020 election, however, were disappointed as the court sent a strong signal it had no interest getting involved with election results, despite an enormous amount of pressure from Trump.

The former President has many times expressed bitter disappointment with the court for failing to rule in his favor to overturn election results, most recently in a Fox News interview last week.

Barrett did not take part in an order on October 28 – two days after her confirmation – when the Supreme Court denied a request from Pennsylvania Republicans to accelerate review of a lower court decision that allowed ballots to be counted up to three days after Election Day. The court’s public information officer said at the time that Barrett did not participate because of the need for a “prompt resolution” and because she had not had time to fully review the filings.

The move was not out of the ordinary for a new justice. But still, it came as Alito, joined by Gorsuch and Thomas, wrote a fiery statement saying that while they “reluctantly concluded” there was not enough time at this “late date” to decide the case before the election, they were troubled.

“There is a strong likelihood that the State Supreme Court decision violates the Federal Constitution,” Alito wrote.

When the case came up again on February 22 the court denied an appeal from Republicans to take up the case. Alito, Gorsuch and Thomas again dissented.

“Now, the election is over, and there is no reason for refusing to decide the important question that these cases pose,” Alito said. It would have taken four justices to take up the case, and there were only three. Barrett, among others, did not raise her hand.

In December, the court also rejected a bid by Texas to overturn the election results in battleground states. In a brief order the court said that Texas did not have the legal right – known as “standing” – to bring the challenge. No full dissents were noted although Alito and Thomas disagreed on a procedural point in a statement.

The election-related votes were in contrast to comments Trump made before the election in which he suggested the justices might end up deciding it. Back then Trump said it would be “important to have nine justices.”

Religious liberty

On another front, eyebrows were raised in early February when a fractured court voted to block California’s Covid-related ban on indoor worship services. Barrett sided with the majority. But she and Kavanuagh did allow other limitations to remain in place.

Penning her first concurring opinion, Barrett didn’t go as far as the churches would have liked and voted to allow California’s prohibition on singing and chanting during indoor services to remain.

“As the case comes to us,” she wrote, “it remains unclear whether the singing ban applies across the board (and thus constitutes a neutral and generally applicable law) or else favors certain sectors (and thus triggers more searching review).” Barrett did not sign on to a statement from Gorsuch, Thomas and Alito who pointed to some confusion and a record that suggested that the music, film and television studios are permitted to sing indoors.

“Even if a full congregation singing hymns is too risky, California does not explain why even a single masked cantor cannot lead worship behind a mask and a plexiglass shield,” Gorsuch said.

Five months in, as is the custom, Barrett has only released one majority opinion in a case concerning the Freedom of Information Act. Because she is the junior-most justice, it’s unlikely this term or next that she would be assigned a blockbuster opinion.