The state of Karnataka, located in southwest India, is known for its silk. Mulberry trees grow in abundance, feeding silkworms and a centuries-old textile industry. But while silkworms prosper here, many people in the industry do not.

In India, the average silk worker is paid less than $3 a day – small compensation for an industry estimated to be valued at over $14 billion globally. Part of the workforce is trapped in bonded labor, a form of modern-day slavery in which people work in often terrible conditions to pay off debt.

Bonded labor was made illegal in India in 1976, but it never went away. A 2018 report estimated around 8 million people in India were unpaid workers or held in debt bondage, though some campaigners believe the true figure is much higher. Exactly how many are involved in the silk industry is unknown.

In January 2020, the CNN Freedom Project visited Sidlaghatta, a silk hub some 65 kilometers northeast of Bangalore, Karnataka, and met Hadia and Naseeba. This mother and daughter were forced by their “master” to work 11 hours a day, for which they earned just 200 rupees (about $2.75) to repay a 100,000-rupee (about $1,370) loan that had since doubled in size.

Naseeba had been working for three years in a silk factory, her mother nine years, boiling silkworm cocoons and removing the threads from which silk is made. The steam was foul and their hands bled, she said.

Read: More on modern-day slavery from the CNN Freedom Project

“(The master) came and he said to my mother, if you will not repay the money then we’ll have a rich man and you will have to go and sleep with that man,” said Naseeba.

“I’m afraid of the owner, because he has given us (a) home to live in,” she added. “Where should we go? We cannot go anywhere. We don’t know what he will do with us after (sees) this video.”

Hadia and Naseeba concealed their faces on camera and agreed to be identified by CNN only after they had received their release certificates.

In India, bonded laborers can approach authorities requesting a certificate of release. If an investigation finds their case to be genuine, they are issued the certificate, which proves their debt is cancelled and entitles them to government assistance. The process can be lengthy – sometimes taking years – and can require bonded laborers to come forward to authorities in the face of social pressures and intimidation.

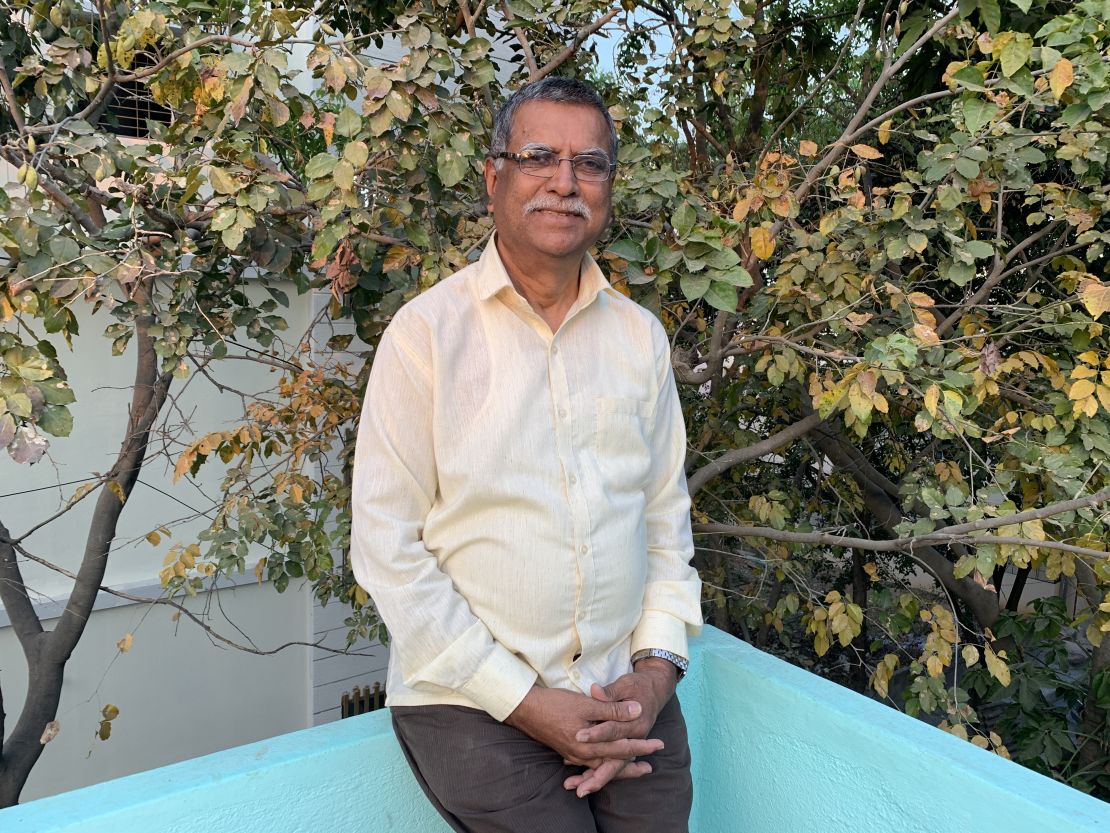

“It is very difficult to convince the bonded laborers (to go to authorities), because they feel that they are beholden to the masters or to the landlords who have helped them in the hour of their need,” said Kiran Kamal Prasad, founder of Jeevika, an organization working to eradicate bonded labor.

Authority figures often come from the same communities as the keepers of bonded laborers, or are the same dominant caste as the landlords, Prasad explained.

“Very often, authorities are not implementing the (Bonded Labor System) Act,” he added. “It takes a tremendous effort from us to make the officials do what they are supposed to do.”

Life after forced labor

Jeevika has allies in people like Shiva Kumar, a senior local government official in Sidlaghatta.

“I grew up as a son of a bonded laborer,” he told CNN. “The (bonded laborers) in the village think that this is their (fate). If they come forward with any complaints, we will file a criminal case against the landlord.”

For Prasad, freedom is only the first step for the victims. “We want to build up the agency of the bonded laborers to (help) them secure justice for themselves,” he said.

Read: The greatest rebuke to the legacy of slavery would be to end it

Programs are emerging in villages, where communities of former slaves are coming together to put their savings into a collective fund. They can draw on the fund should they need it, without having to turn to their former masters – or any other master – for a loan.

Jeevika has helped secure the freedom of nearly 7,000 bond laborers in India in the past six years, and last year it added Hadia and Naseeba to that total. The mother and daughter filed papers and in May 2020, they received their release certificates.

They were escorted by government officials from the silk factory in which they’d toiled for years, and finally felt free enough to show CNN, and the world, their faces once more.