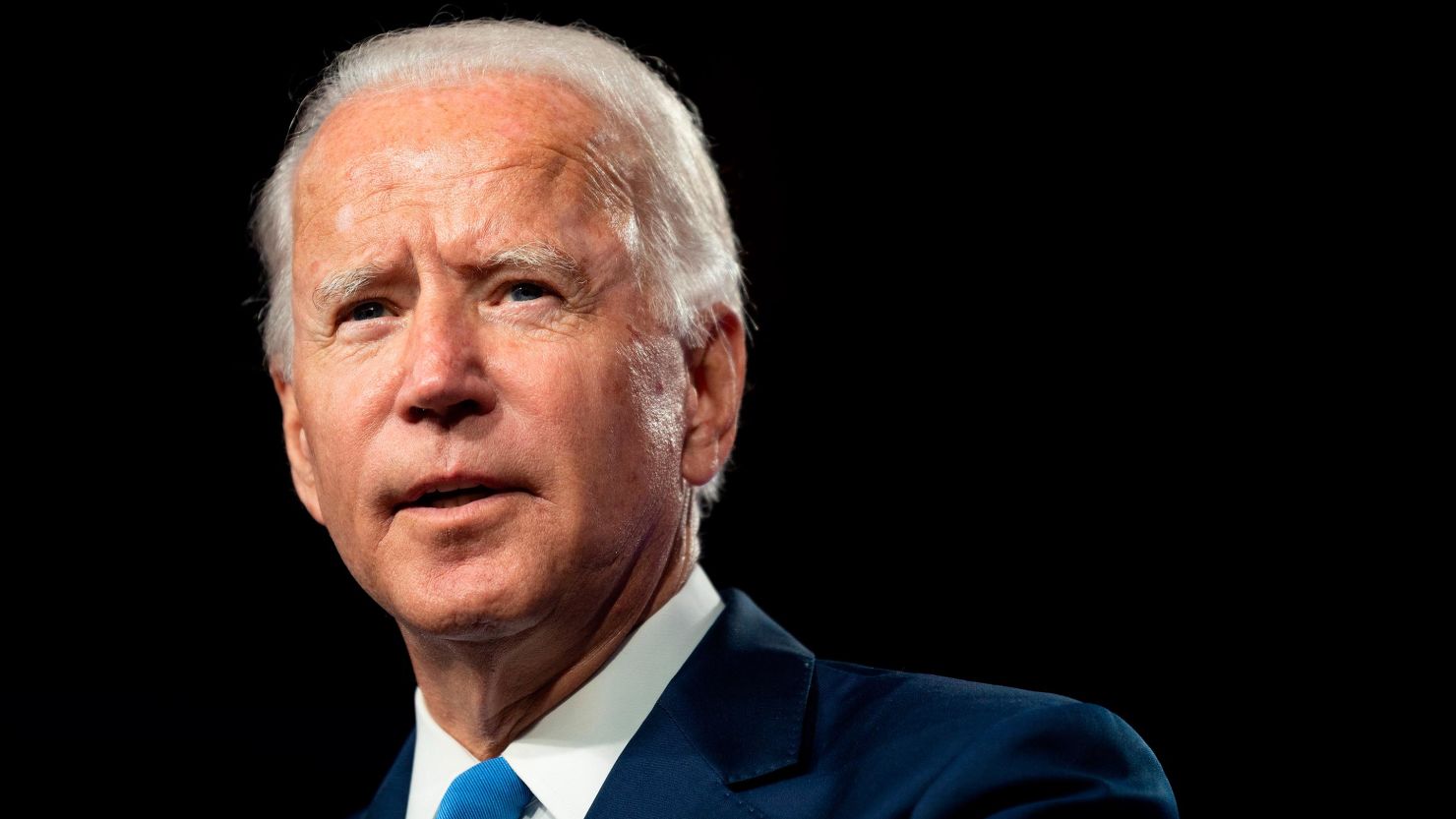

When President Joe Biden welcomed lawmakers into the Oval Office for his very first publicly scheduled meeting with members of Congress, he spoke exclusively with Republican senators – an apparent effort to reach across the aisle to get their support for his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief proposal. Now, a month later, that legislation is being sent to Biden’s desk to sign into law without a single GOP vote of support.

“I’m anxious for us to talk,” Biden said to Maine GOP Sen. Susan Collins during the Oval meeting. “I feel like I’m back in the Senate, which I liked the best of everything I did.”

In the earliest days of his presidency, Biden was predictably optimistic about getting Republican support for his major legislative endeavors. But in many ways, it’s clear that the Washington he now faces is far different from the one he thrived in as a senator – and it remains to be seen if his well-honed skills and governing approach will be met with success in the radically polarized new world.

Over the course of three weeks after taking office, the President would host nearly one-quarter of all US senators in the Oval to discuss his American Rescue Plan and infrastructure. But despite the warm West Wing receptions, any semblance of Republican support for his relief proposal – Biden’s top legislative priority – largely evaporated when Democrats refused to shrink the size of the $1.9 trillion bill. The plan passed along party lines, and Biden, eager to get his first legislative priority out the door, was willing to sacrifice any potential for bipartisan support.

“If I have to choose between getting help right now to Americans who are hurting so badly and getting bogged down in a lengthy negotiation or compromising on a bill that’s up to the crisis, that’s an easy choice,” Biden said in February when he rejected a slimmed-down Republican counterproposal for coronavirus relief. “I am going to help the American people who are hurting now.”

Even with a Democratic majority in both houses of Congress, Biden has already faced battles among those within his own ranks. Democrats bickered over the inclusion of a $15/hour minimum wage hike in the Covid-19 relief bill but were ultimately spared when Senate procedure allowed for a neutral party – the Senate parliamentarian – to rule it out of line. Moderate Democrats also torpedoed the nomination of Neera Tanden, Biden’s pick to lead the Office of Management and Budget.

Despite these early hurdles with both Republicans and Democrats, the President continues to oppose the legislative filibuster, a Senate rule requiring a 60-vote supermajority for most legislation. The White House has indicated that his preference is not to end the rule because it encourages compromise with Republicans.

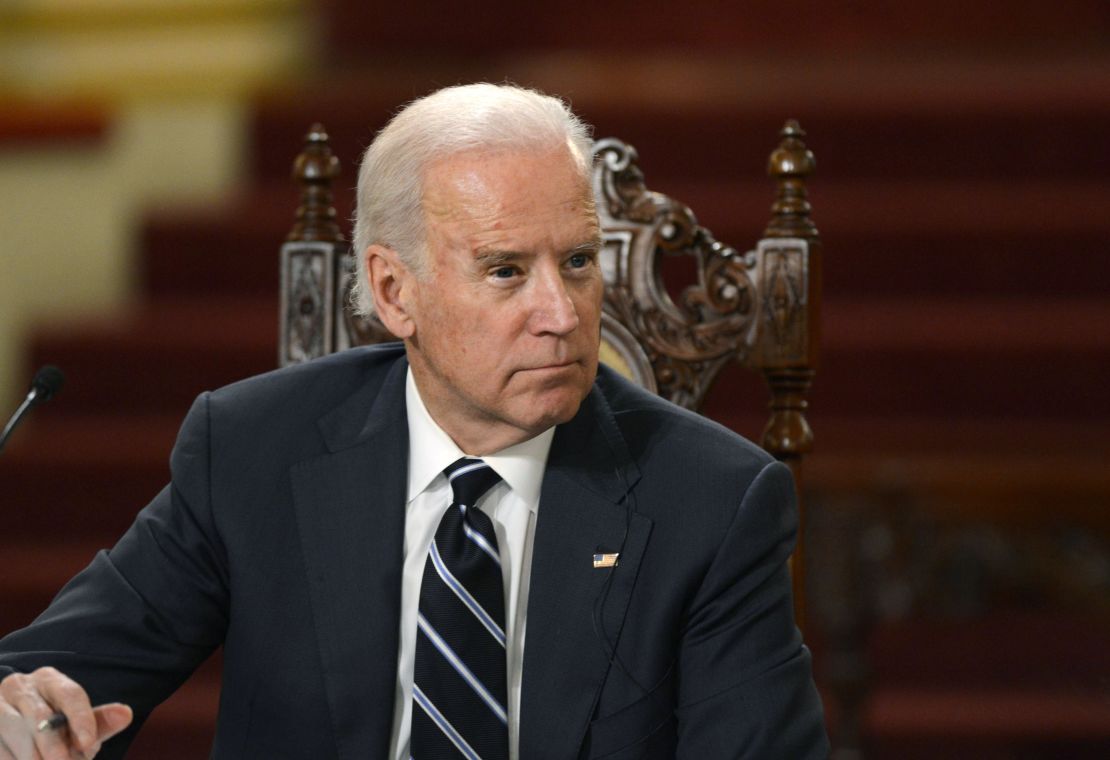

In his near-half century in Washington, Biden held key Senate committee roles and forged unconventional partnerships in Congress with the goal of achieving consensus, even when compromise was necessary to reach a deal.

But in this new era of deal-making in Congress, Biden’s beliefs in the institution of the Senate are being challenged, and his efforts to secure the passage of his American Rescue Plan illustrate just how far he’s willing to go to play the new game.

History in Congress

It took Joe Biden 36 years in the Senate, eight years as vice president, and a few failed presidential runs before he would finally become President of the United States.

At the time of his Senate swearing-in, Biden was among the youngest senators to have ever joined the body of Congress in its history. Now, more than a decade after his departure from the Senate to serve as vice president, Biden still stands as the 18th longest-serving senator in US history.

That Senate experience helped cement his portfolio as vice president, which in many ways reflected his previous priorities as a lawmaker.

He was the top-ranking Democrat on the highly influential Senate Judiciary and Senate Foreign Relations committees for decades. Then,in 2008, Biden served as a sounding board for Obama on national security and foreign policy, according to The New Yorker. And in the Obama White House, Biden subsequently took on a foreign policy-centric portfolio and served as the White House proxy in Congress during contentious moments, like passing the 2009 economic stimulus package and avoiding the fiscal cliff.

Biden’s reputation as a dealmaker throughout his time in the Senate and as vice president was forged by his unconventional partnerships across the aisle.

Sometimes, that meant compromise in addressing the fiscal cliff directly with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

While the compromise was touted as a victory by the Obama administration, some progressives said the administration should have held the line. Democrats such as Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet have subsequently argued “that deal extended almost all those Bush tax cuts permanently.”

In other instances, forging unconventional partnerships in order to get things done included policy debates with figures now considered to have values diametrically opposed to the ones Biden has said are at his core. That included co-sponsoring legislation with South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond, a segregationist, on several crime bills. It also included hashing out several differences in a chemical weapons treaty with North Carolina Republican Sen. Jesse Helms in the 1990s. Helms, who died in 2008, used racial signals in campaigns and fought against establishing a Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday because he felt the civil rights leader held radical political views.

Biden’s return to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue this year also undoubtedly marks a shift in the way the American president approaches lawmakers on the Hill compared to how things were done over the last four years.

Now, there are fewer tweets from the commander in chief personally denigrating members of Congress. The new President in office is not just one who has brought Republicans in for meetings in the Oval Office early in his term, but one who has also congratulated Republican senators for winning their races. And so far, unlike what happened during the Trump years, there have been no known walkouts by the President during White House meetings with members of Congress.

Despite four years of a President calling to drain the swamp, Biden’s many years in Washington, allies argue, is for the better.

“(Biden’s past experience in) the executive branch is not only relevant experience, but I think it’s going to help them enormously as President. Whereas if went right from the Senate, there would certainly be a gap there,” Pennsylvania Democratic Sen. Bob Casey said. “The other thing is, I think he’s made it his business over the years to interact a lot with mayors and governors.”

Biden in action

It’s not clearly known what pushes Biden to pick up the phone or schedule a meeting with lawmakers these days to hash out a deal. But in his first months in office, it’s widely known that he’s making those calls and scheduling those meetings frequently.

When White House press secretary Jen Psaki was asked about Biden’s relationship with West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin – the moderate Democrat who has already proved to be a crucial and fickle vote for the President’s legislative proposals – Psaki said Biden is talking to Manchin and many other lawmakers often.

Biden has a list of seasoned aides dedicated to legislative efforts, but the White House has suggested that he’s involved in a large portion of the direct negotiations with lawmakers himself.

“He speaks with a range of senators and members of Congress and members of the House regularly as well. Obviously, they have meetings here, but he, perhaps because he served for 36 years, certainly doesn’t hesitate to pick up the phone and have a conversation, whether it’s something he agrees with, disagrees with,” Psaki said. “That’s something he’s prone to do, even when it’s not on his schedule for that day. Just when it comes up and it’s an ask somebody makes on the team.”

And his tendency to pick up the phone hasn’t been limited to Capitol Hill.

North Carolina Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper said that since Biden has taken office, the President has sought his advice on how to deal with Republicans.

“He doesn’t have it now, but I have a Republican legislature, and we talked about trying to work with Republicans on a bipartisan basis,” Cooper said. “I’ve done that on a number of occasions. I know that’s something that the President wants. And so, he and I talked about how we had done that.”

Michigan Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, who co-chaired Biden’s inauguration, said he’s known to pick up the phone to talk out of the blue. “My experience with President Biden is he’s very hands on, you know, he really is a person that picks up the phone and get cut straight to the matter at hand,” she said.

Throughout the pandemic, Whitmer said she would “get random phone calls” from then-candidate Biden, checking in and asking, “What’s going on in Michigan? What do I need to understand what is it that Michigan needs during the campaign?”

However, many Republicans don’t seem to think Biden’s call for unity has brought Republicans into the fold adequately.

Biden's First 100 Days

Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Republican from Louisiana, told “State of the Union” last month that the White House’s suggestions of his party being involved in the specifics of the American Rescue Plan were a “joke.”

“You can find one thing, perhaps, where oh my gosh we will get criticized on that, so we will adapt. But the reality is that they put forward a package which reflects the interests of the Democratic constituencies that elected the President,” he said, pointing to a now-nixed funding provision in the bill for San Francisco’s transit system.

“Yes, he was open to unity and bipartisanship,” Cassidy said of Biden. “That has not been this legislation.”

And Sen. Rob Portman, an Ohio Republican, said late last month that he was disappointed the White House had not reached out to Republicans to work on a bipartisan version of the bill.

After the plan passed in the Senate without any Republican votes, Biden said he hadn’t given up on getting their support.

“Look, the American people strongly support what we’re doing. That’s the key here. And that’s going to continue to seep down through the public, including from our Republican friends,” Biden told reporters on Saturday. “There’s a lot of Republicans who came very close. They’ve got a lot of pressure on them. I still haven’t given up on getting their support.”

Changing world

Casey said that despite Biden’s absence from the Senate for over a decade, the President is savvy to the fact that things are not the way they used to be.

“Consensus is the exception, not the rule. For most of Joe Biden’s time in the Senate, it was the opposite,” Casey said, but added, “I think Joe Biden has a better understanding of that than people realize.”

“(During) his eight years as vice president, he was interacting with the Senate in the House on a regular basis. And so, this idea that he doesn’t have an understanding of the current reality is just not factual,” Casey continued. “He has a deep understanding of how different the Senate is today from the time he served.”

“The President is really in his own element,” Steve Ricchetti, one of the President’s top advisers in the White House, told CNN. “It is very natural to him and he has enormous respect for his friends and colleagues in the Congress. He has an established reputation for, you know, his ability, his sagacity, and his insight into the congressional process and what the most effective way to have respectful and successful legislative initiatives are.”

Biden has been eager to push through major legislation quickly, arguing that the urgent need to provide Americans relief amid the coronavirus pandemic supersedes most other political debates. And Democratssuch as Caseydon’t seem concerned he’s burning through political capital too early in his tenure.

Many also argue that it’s advantageous to work quickly during a president’s first year, especially their first 100 days in office, because those first days remain crucial to enacting their agenda.

Even as negotiations for the relief plan were ongoing, Biden and administration officials indicated there would be more to come.

The White House has not decided on what legislative proposals will follow the relief package, Ricchetti said.

“But obviously, we have a short-, medium-, and long-term reconstruction program, a recovery program for the country,” he added.

So far, the White House has signaled willingness to push forward an infrastructure package early in Biden’s term. And even as negotiations over the President’s coronavirus relief package continue, the White House has begun infrastructure talks.

There have been several meetings at the White House to talk about infrastructure, and when the President met with governors and mayors to discuss Covid-19 relief, Arkansas Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson told reporters that an infrastructure bill was brought up as “the next opportunity for bipartisanship.”

Biden also said the would be launching “the next phase of the Covid response” during his upcoming primetime address on Thursday.