Editor’s Note: Abigail Pesta is an award-winning journalist whose investigative reporting has appeared in major publications around the world. She is the author of the new book “The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.” The views expressed here are hers. Read more opinion on CNN.

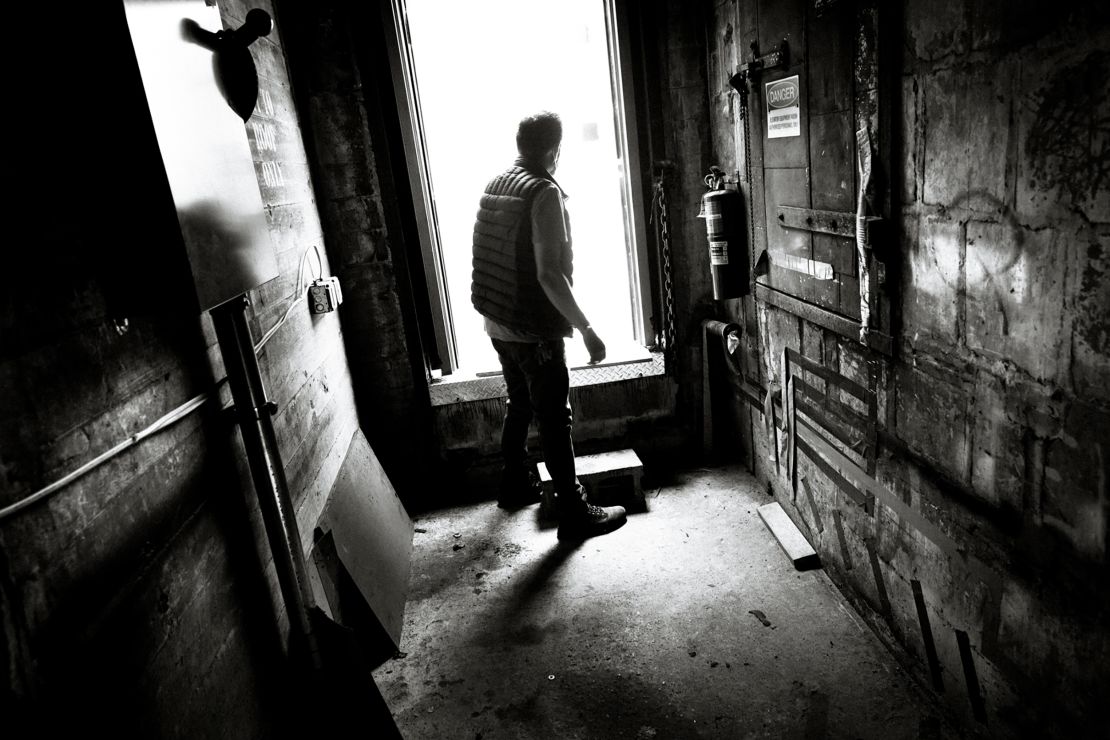

The stretch of Grand Avenue where Onesimo Garcia works in Brooklyn is not exactly grand. It’s a desolate warehouse street, in the shadow of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, where cars roar overhead. There’s a monolithic self-storage place on one end of the block and a trio of empty warehouses on the other, waiting to be demolished. It’s a street where film crews like to stage scenes of drug deals going down. It has that look — all grit and graffiti. But there’s also a tiny garden, growing in a square of dirt carved out of the sidewalk, where sunflowers and roses bloom in the summer.

That’s all Garcia.

He’s the superintendent — the “super” — of a crumbling warehouse that dates back to the early 20th century, when it was a garment factory. Today, the place is an apartment building, housing painters, musicians and performance artists, all in industrial lofts. Garcia has been working here for decades. When he first arrived in the 1980s, the building housed a sweatshop, packed with hundreds of immigrants stitching together clothing for retailers. Back then, he told me, he worked in the shipping department, boxing up the clothes.

Over the years, he has dealt with all kinds of drama in the building. There were the tenants who set fires on the floor of their apartment to stay warm, the woman who built a warren of tiny rooms in her loft and scrawled poetry across the walls, the guy who let his dog use the roof as a toilet. “People are crazy,” he said to me, shaking his head.

But none of it could have prepared him for the way his life would change because of the coronavirus.

As the virus quietly seeped into New York City early last year, Garcia was doing his job as usual, handling people’s trash and packages, fixing the ever-broken elevator, entering apartments to help tenants deal with faulty water heaters and clogged sinks. During this time, misinformation swirled around the virus. President Donald Trump said it would simply disappear. The Surgeon General said the flu was a bigger concern. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said it wasn’t necessary to wear masks for protection.

In March, the truth slammed into focus: The virus was rapidly spreading across New York, destined to kill tens of thousands. Suddenly, nonessential businesses had to close their doors. People needed to start working from home. Hospitals faced the fact that they could run out of lifesaving equipment. New York was on its way to becoming the epicenter of the pandemic.

And with that, the city that never sleeps experienced one of the most extraordinary moments in its history: It was told to shut down.

But not everyone had the luxury of staying home. An army of essential but unappreciated workers had to continue doing their jobs so that the city could function amid the unprecedented crisis. Bus drivers, delivery people, sanitation workers, grocery clerks, hospital janitors, doormen. They risked their lives so others could stay safe, as did essential workers across the country.

Garcia, among them. His is the story of America, and the increasingly dire plight of our workers who keep it running. It’s time to listen. As Congress fights with itself over the minimum wage and how to help families in need, it’s time to ask ourselves: What does America owe its essential workers? What do we owe the people who have risked their lives to keep the country alive amid this deadly crisis? And where will they be — mentally, physically, financially — when the pandemic is over?

When the city closed down last March, Garcia knew he would have to keep going to work. He needed to support his family — his wife and two sons at home in Brooklyn, as well as his father, sister, and two nephews in Mexico. But he feared for his safety every time he walked into the building. “For me to come to work every morning, I feel so afraid something will happen to me,” he told me, noting that the virus has been especially deadly for Latino people like him.

His first move was to pull out a clump of N95 masks he had once bought for construction work. Even though health experts at this point were saying masks weren’t necessary, he thought it would be a good idea to wear one. After all, there was a highly contagious virus in the air. Why not wear a mask? Then he ordered a bunch of paper masks online from China. While awaiting the shipment, he said, “I started wearing one N95 mask a week. You’re not really supposed to wear them more than once, but I only had eight of them, so I cleaned them off with alcohol and let them sit in the sun.”

At work, he tried to limit his direct exposure to people as much as possible, for everyone’s safety. “I told people, whatever’s happening in your apartment, if it’s not an emergency, I can’t go in. Most people understood.” He worried about bringing the virus home to his wife and two sons. He established a routine to try to keep everyone safe at home, promptly shedding his clothes each day after work and tossing them into a black plastic bag, then taking a shower and putting on clean clothes before greeting his family.

And then, one day in April, his wife, Matilde, felt sick after coming home from work at a corporate cafeteria. “She had a bad fever and cough, but she didn’t want to go to the hospital because she knew people were dying there,” Garcia recalled. Indeed, thousands of people had died across New York at this point, with new infections skyrocketing. Doctors and nurses were rapidly using up stocks of protective gear.

As Matilde’s symptoms worsened over the next two days, Garcia convinced her to go to an urgent care clinic in Manhattan to get tested. He went with her and waited outside the clinic, as instructed. Back home, while the couple awaited the test results, their 26-year-old son, Christian, fell sick as well. So Garcia took him to the clinic for a test too.

A few days later, the results came in: Both Matilde and Christian had the virus.

The warehouse on Grand Avenue hasn’t changed much since its factory days, despite the changing face of its tenants. Its windows are so old, it’s hard to see through them, thanks to the cloudy bubbled glass and chicken wire. Garcia has done his best to take care of the place, and its residents, for decades. He tends to his little garden out front, despite the fact that someone stole a pot of roses as soon as he planted them. He puts pumpkins out on the stoop at Halloween, and hangs a wreath on the front door at Christmas. He fields complaints about the overworked washing machines and the clanking, lurching elevator, which likes to leave people trapped between floors.

I know the elevator well because I lived in the building for a time with my brother, Jesse, who still lives there. Over the years, Garcia told us his story. I remember laughing with him one day when he helped me attach an absurd metal pan to the ceiling to catch drips, so rain wouldn’t plop on my head in the kitchen. He began telling me about his journey to America.

Garcia first arrived at the warehouse when he was a teen. The eighth of nine siblings, he had grown up in a poor family in Puebla, Mexico, where his parents served as cooks for a French family. He came to America as an ambitious 18-year-old, with hopes of earning some money to go to college back home in Mexico.

He thought he might work in construction in New York City, as an uncle and older brother did. But getting there wasn’t easy. In February 1985, he boarded a bus in Mexico City, along with a brother and sister, and headed to Tijuana, traveling “two days and two nights,” he recalled, on the dusty, rusting bus. His older brother had arranged for a man in Tijuana to help the three siblings get across the border, making a down payment to secure the man’s help. The plan was for Garcia and his siblings to pay the rest after getting jobs in America.

The three siblings were told where to meet the man on the street one afternoon in Tijuana, with instructions not to get close to him or talk to him, but to follow him from a distance. They did so, hiking out of the city and up a steep hill late into the evening. Then, they waited. “It was dark out, nine or ten at night,” Garcia remembered. “He told us to run when the patrols disappeared.” Indeed, the border agents eventually left, and everyone ran like mad, scrambling for the border. “We ran for thirty, forty minutes,” he said. They made it across the border into California, where they were hustled into a car. A driver spirited them away to San Diego.

There, they boarded a plane bound for New York City, increasing their debt to the man. Airports were a new experience for the family. “We didn’t speak English,” Garcia said. “They just told us to look for an ‘Exit’ sign when we landed in New York.”

In New York, they found a yellow cab and headed to their uncle’s apartment in Brooklyn. “It was snowing so bad,” Garcia told me. “We had no proper clothing for the snow.”

When they arrived at their uncle’s place, they stood out front, shivering for hours as they waited for him to return from work.

It was the beginning of a rude new reality of life in America.

Garcia got a job in the garment factory and began working there 13 hours a day, boxing up the clothes in the shipping department. He worked seven days a week — Sundays to Fridays at the factory, then Saturdays in a restaurant in midtown Manhattan, washing dishes. He earned around $120 a week, he said, and he had a huge debt to pay to the man who helped him get from Mexico to New York. He had other expenses too: he lived with his uncle, so he needed to help pay the rent, in addition to sending money back home to Mexico for his mother, who had recently fallen ill. Suddenly his college dreams seemed further away than ever.

“Back in Mexico, when people used to talk about New York, it sounded like a fantasy to me,” he said. “When I came here, I saw things differently. But I had no choice; I had to stay and finish paying the people I owed. I couldn’t return home.”

And so he slaved away in the factory on Grand Avenue, which was teeth-chatteringly cold in the winter, with frigid air seeping in through cracks in the windows. Summers weren’t much better, when the sun beat down on the black tar roof, roasting the un-air-conditioned building and everyone in it.

When he was 19, Garcia met his wife, Matilde, at the factory, where her job was to put labels on sweaters. They fell in love and later married. She was a US citizen, thanks to an immigration-reform bill that President Ronald Reagan had signed into law in 1986. The law, which imposed penalties on employers who hired undocumented workers, also made immigrants who had entered the country before 1982 eligible for amnesty. Matilde sought amnesty and became a citizen. After the couple married, Garcia became a citizen too.

He kept working away on Grand Avenue, even though the job provided low wages, no benefits, no sick leave, no savings plan and no paid vacation. But Garcia had no choice but to keep working. He needed the job, especially when his wife gave birth to two boys, Christian and Juan.

Eventually the factory shut down, the building got divided into apartments and he became the super. In typical Garcia style, he added creative touches to the lofts when he could, like hanging a vintage chandelier with fringe lampshades he had found abandoned in a corner of the factory. The building got sold, then sold again. He kept taking care of the place.

He set a goal of helping his sons get to college one day, hoping they could achieve the dream that he had not.

When Matilde and Christian tested positive for the virus, they hunkered down in separate bedrooms to quarantine for two weeks, as directed by the health care workers at the clinic. “They were told to stay home, and if they couldn’t breathe, to go to the emergency room,” Onesimo said. “Everyone was wearing a mask inside the apartment. It was so scary.” Indeed, bodies were piling up across the city, with refrigerated trucks parked outside the hospitals to handle the overflow. Ambulance sirens wailed around the clock.

Amid the spiraling tragedy, mixed messages from officials continued, with the President continuing to claim the virus would disappear. The CDC reversed course on its earlier advice, now recommending that people wear masks. For many essential workers, that advice came too late, with bus drivers among the hardest hit.

Garcia and his 22-year-old son, Juan, became caretakers, delivering Tylenol and soup to Matilde and Christian, while trying to keep their distance from their loved ones in their own home. Matilde was harder hit than Christian, suffering a dangerously high fever and cough. There were times she became so delirious from fever, Garcia said, “she was talking to herself.” The family wondered if she should go to the hospital, but she remained reluctant. Going to the hospital, where she would be surrounded by dying people, felt terrifying, and she wouldn’t be able to see her family, as visitors weren’t allowed. People were dying alone, without a chance to say goodbye to their spouses, parents or children. Since Matilde was still able to breathe, she stayed home.

As for Garcia, he couldn’t afford to stop working, despite the crisis at home. He soldiered on, wearing a mask and gloves as he tried his best to stay away from everyone, both at work and at home. His wife received pay for sick leave and the family had health insurance through her work, so for the time being, they felt they could survive.

Around a week later, Matilde’s fever broke. “One day I saw her and she had no more fever; I was so relieved,” Garcia recalled. “She was looking better and I said, ‘Oh my god, thank god.’ I know people who had died from it.” Christian also cleared the virus and Garcia tested negative, twice. They thought they could move forward.

But then, another blow: Matilde got laid off. The corporate cafeteria where she worked no longer needed her services because the employees of the company were working from home. With the loss of that job, the family lost its health insurance. Garcia kept working and scrambled to find a family health insurance plan he could afford.

He and his family now have hardly any savings, due to decades of low pay. “I was never able to save much for retirement,” he told me. “I’ve worked 35 years in this building, with no 401(k), no nothing.”

The pandemic has exposed the complete lack of a safety net for workers like Garcia — and the glaring inequity that America will be struggling with socially and politically for years to come. Long after the virus, the inequality hangover will remain. More than ever, these workers will be at the mercy of their employers, if they don’t lose their jobs altogether. Many will experience a singular kind of post-traumatic stress from serving on the front lines.

Despite it all, Garcia has managed to achieve one dream: getting his boys educated. It’s a testament to his resilience, and his strength. With the help of financial aid, Christian graduated from college with honors; Juan attended college for a year and plans to finish up at a trade school while he saves money from working at a gym. Garcia hopes they will have a better future than the one he sees for himself in America.

He, like so many essential workers across America, lives on a knife edge.