Editor’s Note: Nicole Hemmer is an associate research scholar at Columbia University with the Obama Presidency Oral History Project and the author of “Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics.” She co-hosts the history podcast “Past Present” and “This Day in Esoteric Political History.” The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion articles on CNN.

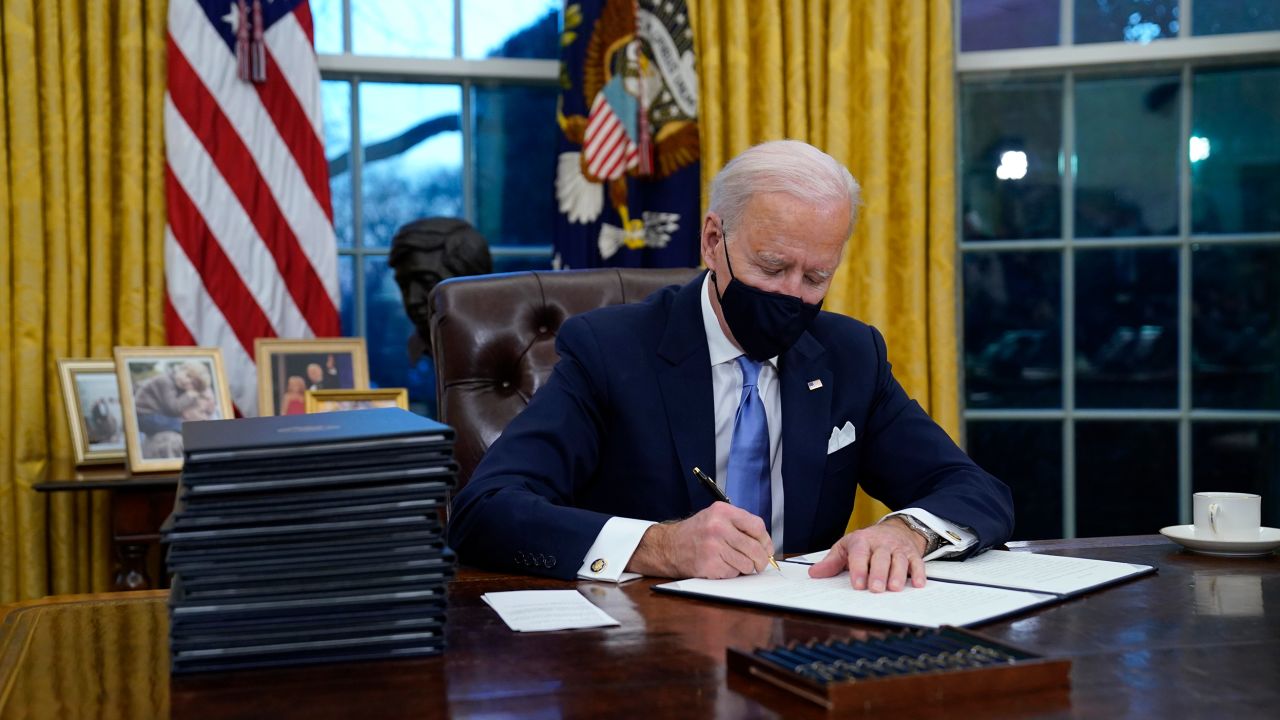

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden signed a stack of executive orders, doing everything from rescinding the Muslim travel ban to reversing the US departure from the World Health Organization to asking federal agencies to extend their moratoriums on foreclosure and eviction during the pandemic. But he also revoked one of the Trump administration’s final projects: the 1776 Commission.

The commission, an advisory committee of academics and conservative activists convened by then-President Donald Trump, issued a 41-page report on Monday, seeking to counter the 1619 Project, a New York Times initiative that explored the central role of slavery and anti-Black racism in US history.

Denouncing works that “tell America’s story solely as one of oppression and victimhood,” the 1776 Commission’s report insists that real history is history that focuses on the country’s successes, with only an occasional nod to its failures.

The people behind the report had been directed by Trump to develop a program for “patriotic education.” And while the report has little to do with academic history – it has no footnotes or sources, and large chunks appear to be cribbed from op-eds and other polemics – it exemplifies the worst misuses of history during the Trump era: as myth and propaganda.

The report itself does not amount to much. It is the detritus of the waning days of the Trump administration, a bit of unfinished business sent out the door in the closing hours and now swept away by an incoming administration. But as a study in the growth of right-wing pseudohistory, it’s a key document.

As pseudohistory, it argues from ideology rather than evidence, starting with an argument – that all bad things come from the left – and then pretzeling the past to fit a politically expedient thesis, one that deliberately erases the need to grapple with things like racism or contradiction. Under the Trump administration, proponents of this ideology reached a new peak of influence, and Trump’s defeat does not relegate them to the fringe.

Reading history through the 1776 Commission’s ideological lens produces some pretty strange conclusions. In the report, anti-racists and anti-fascists are the successors of enslavers and Nazis.

John C. Calhoun, an ardent defender of slavery who argued that it was not “a necessary evil” but “a positive good,” becomes, in the commission’s telling, the father of identity politics. An appendix draws a straight line from Calhoun to today’s civil rights activists – the very ones who have committed themselves to dismantling White supremacy.

That bizarre argument is not original to the 1776 Commission. Over the past few decades, a cottage industry of right-wing histories has thrived in the United States, making up in sales what they lack in credibility.

But they do more than fatten their authors’ wallets: they are part of the alternative reality constructed by conservative media. (Not coincidentally, many of the authors of these books are right-wing media figures, from Brian Kilmeade and Glenn Beck to Dinesh D’Souza and Bill O’Reilly.)

The master of the genre is D’Souza, and it’s worth noting that the vice chair of the commission is a favorite of his, political scientist Carol Swain, who features heavily in his documentaries. Over the past decade, D’Souza has pumped out a steady stream of books and documentaries aimed at rewriting history so that every dark action can be traced to the Democratic Party and the modern left. The histories themselves are fatuous, as I’ve explored in-depth elsewhere, relying on the basic claim that the Democratic Party was pro-slavery in the 19th century so must necessarily be racist today.

That tissue-thin argument does not stand up to any rigorous scrutiny. But it’s not meant to. The point of these pseudohistories is not to construct a careful argument about the past – or to educate anyone looking to know more – but rather a set of talking points that can be used to shut down any meaningful conversation about racism.

The 1776 Commission is written from that same defensive crouch. Rather than engage in a conversation about the way racism has shaped the history and institutions of the United States, they have written a field guide for dismissing such discussions as efforts to “demean America’s heritage, dishonor our heroes, or deny our principles.”

The commission’s stated aim of “patriotic education” was part of a broader right-wing effort to refocus attention on how schools teach American history. The entire enterprise was motivated in part by the decision by the 1619 Project’s creators to release a guide for using their project in classrooms.

Many right-wing politicians recoiled at the inclusion of new scholarship on the persistent influence of slavery and discrimination in the United States. In September 2020, the same month he announced the 1776 commission, Trump tweeted that schools using the 1619 Project “will not be funded!” and Sen. Tom Cotton proposed legislation that would ban its use in schools. The education fight gave detractors’ grievances against the 1619 Project urgency and heft: they knew that if it became part of children’s education, it could have an even greater impact on how Americans view their past.

Despite the carelessness with which many of these far-right conservatives treat history, they understand how important, and how powerful, our historical narratives are. The stories we tell about our past inform our understanding of the present and our vision for the future. That’s why the battles over history are so fierce.

The early 1990s saw a debate over public history and school curriculums so pitched it became known as “the history wars.” Just a few years ago, conservatives attempted to rewrite Advanced Placement standards to give US history a rosier glow.

In more recent years, Black activists have challenged the whitewashed history of the Confederacy represented by unapologetic displays of the Confederate flag and the monuments to Confederate leaders, sparking increasingly visible – and in the case of Unite the Right in Charlottesville, deadly — clashes in the shadows of those monuments.

Even Trump’s slogan, “Make America Great Again,” was rooted in an argument over history: that there was an Edenic national past that had been lost, and that former President Trump vowed to restore.

These fights over our past are critically important, but as the 1776 report shows, they are not always fought in good faith. President Biden dedicated part of his inaugural address to a defense of truth. “There is truth and there are lies, lies told for power and for profit,” he said. “And each of us has a duty and responsibility, as citizens, as Americans, and especially as leaders, leaders who have pledged to honor our Constitution and protect our nation, to defend the truth and defeat the lies.”

In dissolving the 1776 Commission on his first day in office, President Biden helped end one source of misinformation about our past, a reminder that, as we work to restore democracy, we will need to restore honest inquiry and accurate history as well.