During a live virtual press conference on Thursday, a stunned global audience watched as singer-turned-politician Robert Kyagulanyi, known as Bobi Wine, was forcibly removed from his vehicle by Ugandan police as gunshots were fired.

“I have regularly been beaten and pepper-sprayed on the campaign trail,” Wine, who escaped unhurt from the incident, told CNN in a phone conversation two days prior to the incident.

“The military has taken control, and this was never a fair and free election.”

Following the incident, the conference organizers, Vanguard Africa, a nonprofit promoting democracy in African countries, filed a complaint with the International Criminal Court against Museveni and other high-ranking Ugandan officials for “violations of international law governing human rights and crimes against humanity.”

Ugandans go to the polls on January 14, with Wine and nine other candidates challenging incumbent President Yoweri Museveni, commander-in-chief of the military, who has been in power since 1986, a tenure marked by an assault on democracy, critics say.

Assaults on democracy

In 2005, the Ugandan parliament removed presidential term limits to allow Museveni to remain in office. During the 2016 election his closest competitor, opposition leader Kizza Besigye, was put under “preventive arrest” at his home in Kampala, along with six officials from his party.

Like Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and others in recent history, Museveni, 76, does not appear eager to let a fair and free democratic election unfold after more than three decades in power. In 2017, he changed the constitution to remove the age limit to allow him to extend his iron grip on power. This led to an outcry and street protests among Uganda’s youth.

Wine, who regularly wears a helmet and flak jacket on the campaign trail, is seen as the most prominent challenger, ?and his message has struck a chord with Uganda’s young people.

World Bank data shows three-quarters of Ugandans are under the age of 30 and have never known another president.

Senior US politicians and human rights groups have expressed concern over what they describe as Uganda’s slide toward authoritarianism as Museveni prepares to work with his seventh US President.

They have accused him of attacking the press, allowing military and police brutality, suspending opposition campaigning, and arresting activists in a bid to cling to power.

On Tuesday, two days ahead of the polls, internet service providers were ordered to block access to social media platforms, according to Reuters.

In an address to the nation on the same day, Museveni confirmed that Facebook and other social media was blocked, accusing them of “arrogance”.

Facebook told CNN on Monday it had removed accounts linked to the Government Citizens Interaction Center at the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology in Uganda for using “fake and duplicate accounts” to make the government “appear more popular” than they were.

The President said that any state interference in Bobi Wine’s attempts to campaign was because he has been violating health measures during the pandemic, saying that the virus “has killed very many people in Europe and in the United States.

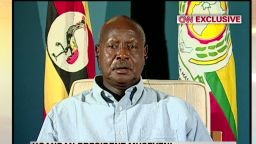

In an interview with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour on Tuesday, he said that Wine ran into “conflicts with the law,” because he defied bans on public gatherings.

However, Museveni himself has held campaign events and there have been calls from opposition candidates for Uganda’s Electoral Commission to sanction all parties who flout Covid-19 campaign guidelines, including the President’s.

The President added in the interview that he would “accept the results” if he lost.

“Uganda is not my house… if the people of Uganda don’t want me to help them with their issues, I go and deal with my personal issues very happily.”

An iron grip on power

Museveni has maintained an iron grip on power in Uganda for nearly 35 years with help from Western allies and many say that the US is complicit in the anti-democratic tendencies of their staunch military ally.

“The United States helps Museveni stay in power,” Wine told CNN on January 5. “If democracy is important, they should reconsider giving Uganda money used to murder and oppress.”

The longstanding relationship between the US and Uganda has meant that the East African country has received nearly $800m a year in aid between 2016 and 2019, according to USAID figures. While other countries like Kenya and Nigeria received more in the same time period for various reasons, the aid to Uganda from the US has still offered legitimacy to an undemocratic regime, commentators say.

“Museveni is a smart player,” said Ken Opalo, an assistant professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, who has written on Museveni’s foreign policy. “He realized he could be a useful ally to the US in the war on terror but also in stabilizing the Great Lakes region [of East Africa].”

This partnership means the US government plays a key role in “professionalizing” the military, the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF), says the State Department on its website. It has also received hundreds of millions of dollars worth of hardware from the US, said Opalo.

Museveni has proved useful, particularly in the fight against terror, added Opalo. Since he seized power following a guerrilla struggle against the government, Uganda has been a source of regional stability, committing troops and working closely with successive US administrations.

Human rights groups and opposition candidates often accuse the security forces of abuse and blurring the line between military and police enforcement.

Arbitrary arrests, detentions, and beatings are common in Uganda.

“UPDF has been involved in incidents alongside the police,” Otsieno Namwaya, the East Africa director of Human Rights Watch, an NGO that advocates for human rights, told CNN.

Neither the UPDF nor Ugandan police responded to CNN’s requests for comment on these allegations.

At least 45 were killed in protests in November sparked by the arrest of Wine and another opposition candidate, Patrick Oboi Amuriat, for breaking coronavirus regulations.

Since then, Wine has said he has been blocked from holding campaign activities several times. He has also accused security forces of shooting at and teargassing him.

Human rights lawyer Nicholas Opiyo was arrested on December 22 by a “security and financial intelligence” team for “money laundering and related malicious acts.” He helped Wine out of military detention in 2018, and has since been granted bail but the arrest was met with international condemnation.

The US Senate Foreign Relations Committee criticized Opiyo’s arrest and said it reflected “the dangerous environment” created to “marginalize and repress civil society.”

Wine’s bodyguard was run over and killed by a UPDF military-police truck, but a spokesperson for the Ugandan military denied it was a targeted attack.

All bark no bite

High-ranking US officials were vocal about the outbreak of violence in the country late last year. On December 9, the House Committee on Foreign Affairs asked the State Department to “review all non-humanitarian assistance to Uganda.”

The next day?, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a tweet the US was “paying close attention to the actions of individuals who seek to impede the ongoing democratic process.”

Senator Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, introduced a Senate resolution on December 17 calling on Museveni’s government to “create conditions for credible democratic elections.”

Yet military aid has not been withdrawn, and the US continues to train Uganda’s soldiers, Opalo told CNN.

When contacted by CNN, Menendez urged Museveni to “allow the people of Uganda to participate in a transparent election and respect their will.”

“I am deeply concerned about the long-term consequences of this crisis for our nation’s credibility as we continue to support democracy around the world,” he told CNN in a statement. “On January 14, the Ugandan people must be given an opportunity to have their voices heard. The Museveni regime’s continued assault on political opposition, media and dissenting voices must stop,” Menendez added.

A cordial economic relationship

The US and Uganda have had diplomatic relations since 1962, following the East African country’s independence from the United Kingdom.

After Museveni seized power, Uganda became relatively stable and experienced economic growth. Uganda is eligible for preferential trade benefits under the African Growth and Opportunity Act and US exports include machinery, optical and medical instruments, wheat, and aircraft, says the State Department on its website.

Despite the rampant corruption, economic mismanagement, misuse of public funds, and discriminatory legal systems listed by the State Department, Uganda received at least $434 million in US foreign assistance in 2020.

A State Department Spokesperson told CNN that the department is “paying close attention to the actions of individuals and organizations who seek to impede the ongoing democratic process…”

Wine says he has a five-point plan which pledges to reduce corruption, but he knows he faces an uphill task. Museveni has seen off many worthy challengers during his tenure, and this time might be no different.

“Part of Museveni’s strategy is to leverage all the instability around him and it’s worked for him; he’s stayed in power for 35 years. But it has been terrible for Uganda,” said Opalo.