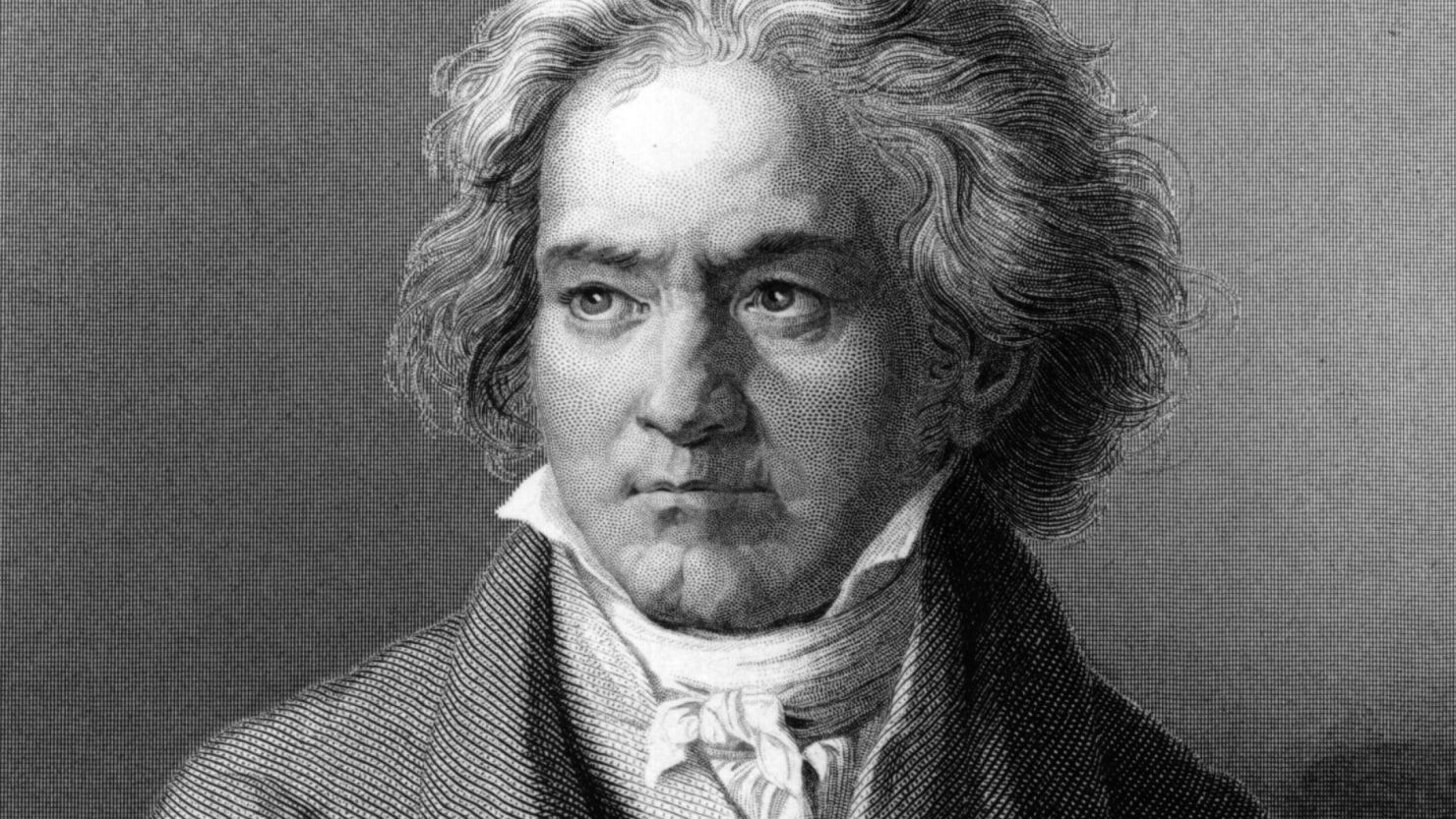

Editor’s Note: Jan Swafford is a composer and music scholar who has written biographies of Beethoven, Brahms and Charles Ives. His new book is “Mozart: The Reign of Love.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

The spring of 1809 found Ludwig van Beethoven in Vienna, huddled in the basement of his brother’s house clutching pillows over his ears. He was in the process of going deaf, but he could still hear the thunder of Napoleon’s cannons shelling the city.

Soon French soldiers would be marching through the streets. It was the middle of the Napoleonic Wars, which roiled Europe for 15 years. Like all the citizens of Vienna, Beethoven would witness the whole wretched spectacle of war: cannons, sieges, occupying troops, funeral marches and thousands of wounded all over the city.

It’s worth reflecting on that time this year as we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the birth of Beethoven, on the 16th or 17th of December, 1770.

Five years earlier, the composer had finished his Third Symphony, which we know as the “Eroica” (which means “heroic”), but was originally titled “Bonaparte.” Its tumultuous first movement conjures images of a battle or a military campaign. It is a piece about Napoleon as hero, conqueror and liberator. In those years Napoleon painted himself in those terms. Like many political progressives at the time, Beethoven saw him as a leader who could bring better laws, better societies and eventually peace across Europe.

In writing a symphony evoking the man who embodied the revolutionary spirit of the age, who proposed to complete the work of the French Revolution, Beethoven was attaching his art to the most powerful figure in the world, which is to say attaching himself to history, and declaring that as an artist he was not simply an entertainer but a part of history as well. The idea that a composer’s work could become part of an enduring repertoire was quite new.

Beethoven was one of the first composers to think of himself in the context of history, to use the word “immortal” concerning his ambitions for his work. That, in itself, did not make him a great composer, but it helped make him a new kind of composer, concerned with the place of his music in the future. And in the course of his career, from his full maturity onward, a series of his works share a train of thought about heroes and society.

I don’t believe that the main importance of an artist’s work is his or her relevance to the present moment. In art there are other significant matters, such as how compelling and moving and eloquent the work is. But the train of thought in Beethoven that I’m talking about has considerable relevance to the contrapuntal predicaments we have found ourselves in during the past year: in the US, with an incompetent and anti-democratic administration on which is superimposed a global plague.

Given the “Eroica” symphony’s focus on Napoleon, the symphony begins with an evocation of a battle or campaign. The second movement recalls what inevitably follows a battle: it is a mournful funeral march. The finale begins with an everyday little dance tune that is gradually transformed into a heroic affirmation. Which is to say that the finale is an image of the ideal society that the hero has bestowed, in which the common becomes exalted. The symphony ends in jubilation.

Beethoven shared with many progressive Germans of his time the belief that human progress was going to come from leaders who would shape enlightened societies from the top down. This image of strong, wise princes is embodied in the term “benevolent despots.” They included Frederick the Great of Prussia and Joseph II, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

Napoleon presented himself as the benevolent despot who would complete the work of those men and of the Revolution (though the French initially believed in a bottom-up revolution that in its course would obliterate all princes).

Beethoven’s full maturity, what we call his Heroic Period, is named for the “Eroica.” By no means are all his works of this period in the heroic style, but the image of the hero was something that occupied him in those years, starting with the Third Symphony.

In his opera “Fidelio,” a tyrant has imprisoned a woman’s husband because of his enlightened ideals and he is being starved to death in a dungeon. Disguising herself as a man, she gets a job in the prison and in the end manages not only to save her husband but to bring down the tyrant. So here is a study not of a world-changing leader, but of individual heroism that changes a society.

Also from the Heroic Period is the mighty Fifth Symphony. Famously, the piece moves “from darkness to light,” from the raging, implacable first movement to a triumphant ending. Beethoven did not attach a dramatic title to the Fifth as he did with the “Eroica,” but he said that every piece he wrote had a story or an image behind it, something drawn from life, whether political or dramatic or emotional.

What I see in the Fifth is a story of inward heroism, of a personal triumph over one’s own fate and one’s own demons. For a composer who has realized that he is doomed to lose his most precious faculty, his hearing, it is not a stretch to find the Fifth as, among other things, an image of Beethoven’s own defiance of fate. It is at the same time the story of everyone’s struggle with what life hands us.

These pieces are of manifest relevance in a time when we need not conquering heroes but good leaders who can help give us better governments. And in a time of plague we need to find our own strengths and sometimes our own private heroism. These are simple lessons, but one of the functions of art can be to teach them, and Beethoven does that with incomparable power.

After those three works, Beethoven was not finished thinking about heroes. Near the end of his life, now almost completely deaf and able to hear music only in his head, he picked up some famous verses of Friedrich Schiller that he had once considered setting to music when he was a teenager.

The poem is an artifact of the revolutionary decade of the 1780s: “Ode to Joy.” It was set to music many times and sung by revolutionaries in the streets. But by the time Beethoven came to use those verses in his Ninth Symphony, Europe had changed for the worse. Napoleon, the last of the benevolent despots, had gone down, and other leaders perceived as progressive had failed. German lands had become police states.

Beethoven understood that the great dream of heroes who would bestow enlightenment was dead. Napoleon had made himself an emperor, revealed himself as another tyrant, and Beethoven took his name off the Third Symphony.

By way of Schiller’s poem, in the Ninth Symphony Beethoven declared that the ideal society, Elysium, was going to rise not from heroes and not from God, but was something that we must do for ourselves as brothers and sisters, as husbands and wives and as citizens in the brotherhood of humanity.

With the Ninth, in a dark time Beethoven wanted to keep the dream of freedom alive, because only through freedom can we find joy. This is another simple message, but one of timeless importance.