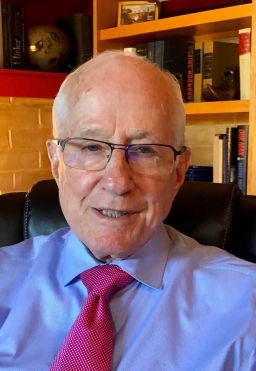

Editor’s Note: Jim Kolbe represented Southern Arizona in Congress from 1984 to 2006. Since retiring from Congress, he has served as a Senior Transatlantic Fellow for the German Marshall Fund of the United States and on the Board of Advisors for McLarty Associates, a strategic consulting firm. He also serves on the boards for the International Republican Institute, Freedom House, The Bretton Woods Committee and the Project on Middle East Democracy. The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Conceding an election is never easy. I know from painful experience. When I first ran for Congress in southern Arizona in 1982, everyone predicted a tight race, and they were right. By 1 a.m. on election night I was certain that my opponent had won. It was narrow – less than 3,000 votes – but I knew from looking at the numbers that we weren’t going to prevail, despite the never-say-die attitude of my staff.

I went into a private room to call my Democratic Party opponent, Jim McNulty, who was gracious in accepting the admission of my defeat. Was that phone call nothing more than a tea-service ritual? No, for several important reasons.

First, it is simply the polite course of action that models this behavior for everyone watching. Just as tennis or football competitors – winners and losers – shake hands or embrace at the end of a game, acknowledging your defeat in a political contest is a mark of graciousness.

Friends and supporters also need to know they were part of a good fight alongside you, but that you have acknowledged that everyone needs to get on with other aspects of their lives. It is also important for government officials and the public at large to have certainty about who will fill the office and to be able to make plans accordingly. They need to know the new agenda as soon as possible.

The president of the United States is not just the highest office in the country, but also the one where the transition can be the stickiest and even most dangerous. Our global adversaries will not stand in the wings politely waiting for us to resolve our election. Any vacuum of power provides an extreme vulnerability. A smooth and orderly transition closes the gap.

This is no idle fear. More than 15 years ago, the 9/11 Commission pointed out that the rapid-fire transition between President Bill Clinton and President George W. Bush, rushed through after a disputed ballot count in Florida, resulted in national security vulnerabilities. “The dispute over the election and the 36-day delay cut in half the normal transition period,” said the report. “Given that a presidential election in the United States brings wholesale change in personnel, this loss of time hampered the new administration in identifying, recruiting, clearing, and obtaining Senate confirmation of key appointees.” Some of these organizational gaps had yet to be resolved by the morning of the attacks on September 11, 2001.

Failure to concede an election when the outcome is certain and beyond doubt undermines the very foundation of our democracy – the public confidence that elections decide who will guide the country or the state or the city. Pointless disputes over fictional “fraud” only fuels disinformation, increases distrust in our constitutional form of government, and weakens trust in their leaders and the very process of holding elections.

Losing an election is never fun. Publicly admitting your loss – conceding the election to your opponent – can be painful, especially for those who have built a career around the cultivation of their image as a winner. But it is a necessary step in maintaining our constitutional form of government. Nobody who is unprepared to take this step should think of running for office.