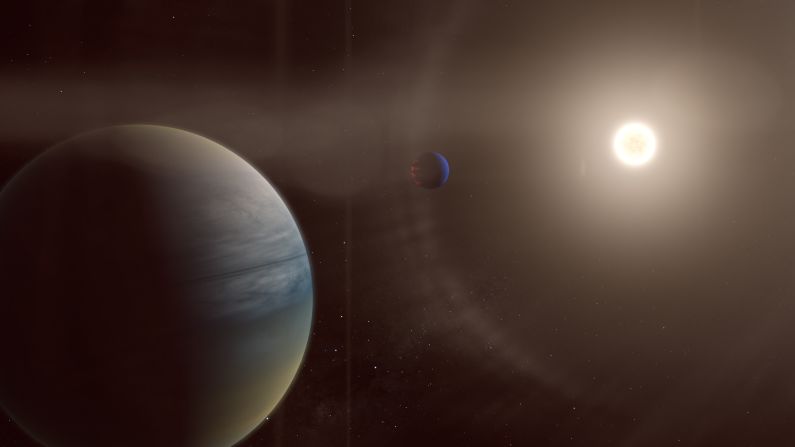

Our galaxy is filled with potentially habitable planets – at least 300 million of them, according to NASA.

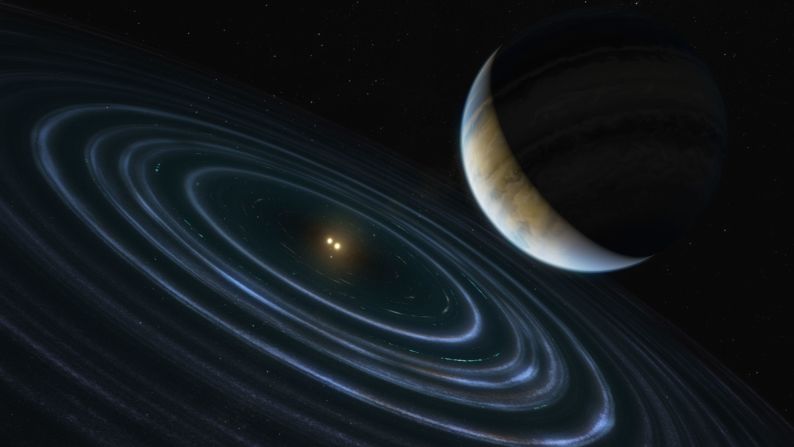

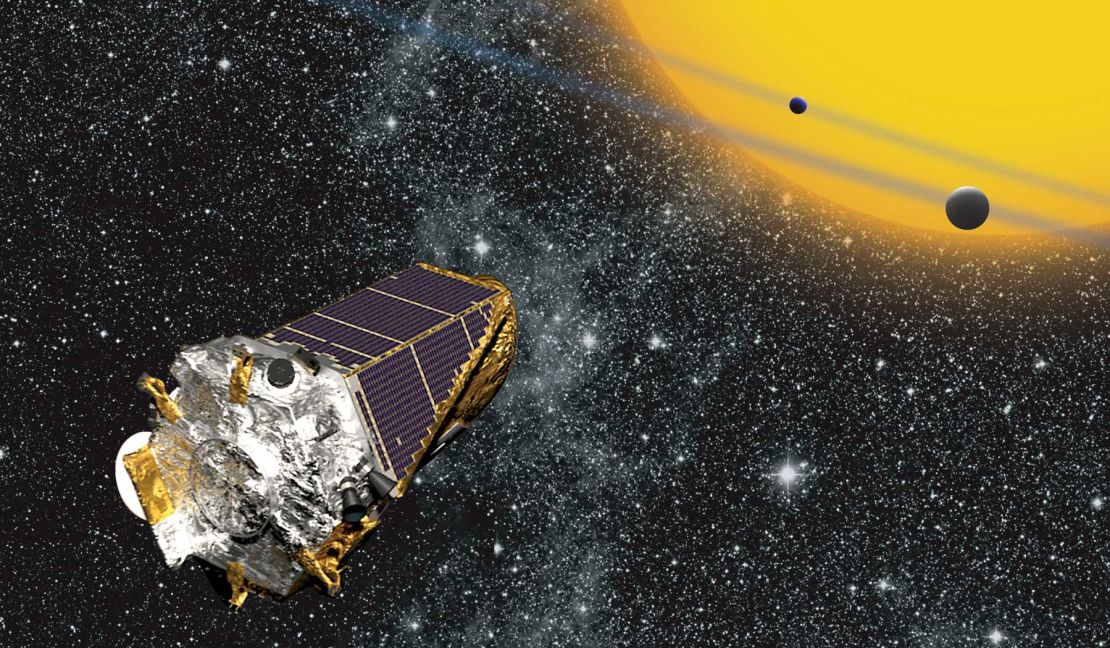

The US space agency’s Kepler Space Telescope spent nine years on a planet-hunting mission, successfully identifying thousands of exoplanets in our galaxy before running out of fuel in 2018. But the original mission’s core question remained: how many of these planets are habitable?

Scientists around the world pored over Kepler’s data for years – and they think they’ve found the answer. According to research released in The Astronomical Journal, there are roughly 300 million potentially habitable worlds in our galaxy, meaning rocky planets capable of supporting liquid water on their surface.

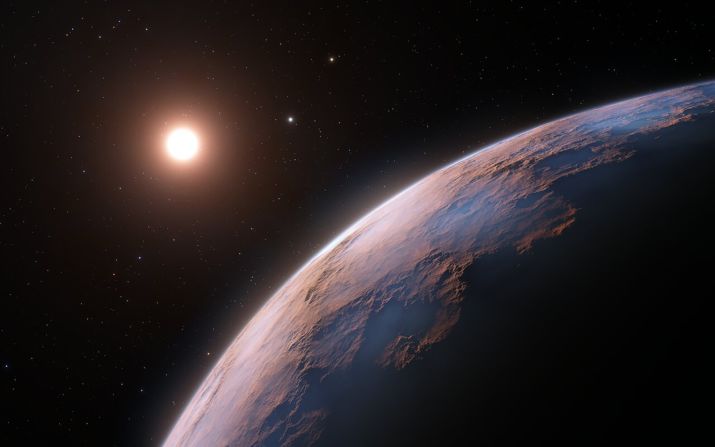

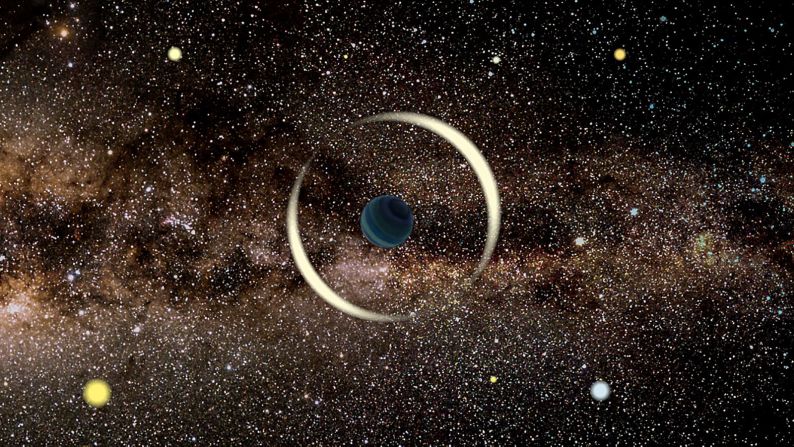

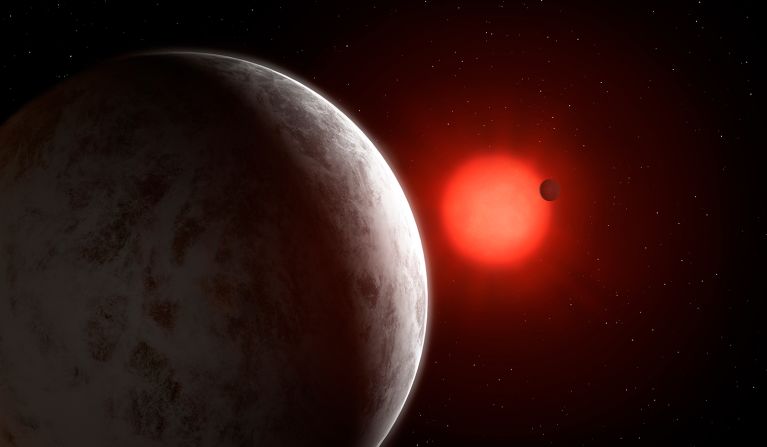

That figure is a rough estimate on the conservative side, and “there could be many more,” said NASA in a news release. Some of these planets could be close enough to be considered “interstellar neighbors” – the closest is around 20 light-years away.

“Kepler already told us there were billions of planets, but now we know a good chunk of those planets might be rocky and habitable,” said NASA researcher and lead author Steve Bryson in the release.

“Though this result is far from a final value, and water on a planet’s surface is only one of many factors to support life, it’s extremely exciting that we calculated these worlds are this common with such high confidence and precision.”

The study was a global collaboration between NASA scientists who worked on the Kepler mission, and researchers from international agencies ranging from Brazil to Denmark.

How they did it

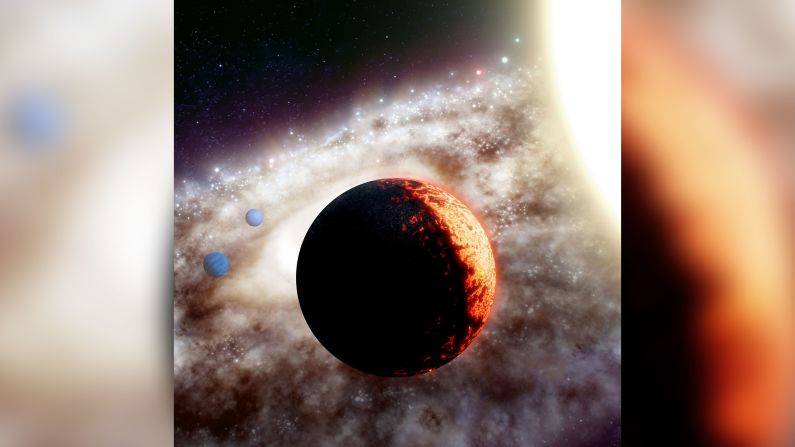

There are about 100 to 400 billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy, according to NASA estimates. Every star in the sky probably hosts at least one planet – meaning there are likely trillions of planets out there, of which we have only discovered and confirmed a few thousand.

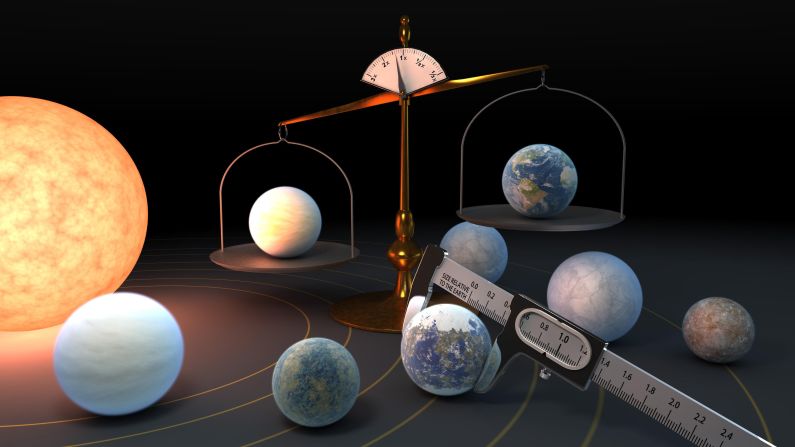

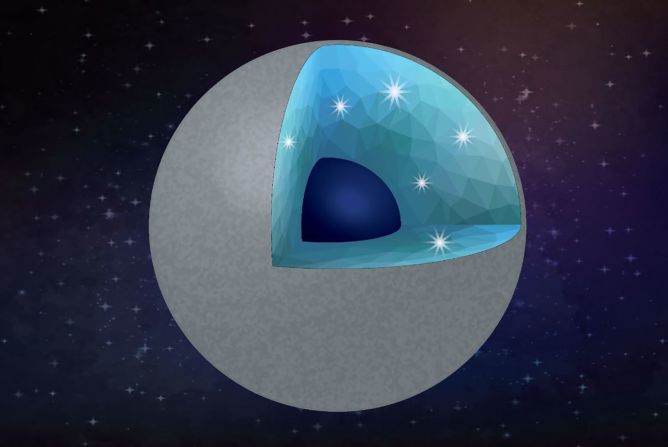

A lot of factors that influence whether a planet can support life, including its atmosphere and chemical composition. But to narrow down the trillions, the researchers in this study focused on a few basic requirements.

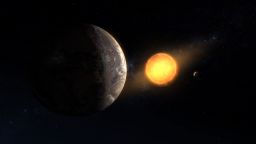

They looked for stars similar to our own Sun in age and temperature, so it wouldn’t be too hot or active. They also looked for exoplanets with a similar radius to Earth, and singled out those that were likely to be rocky.

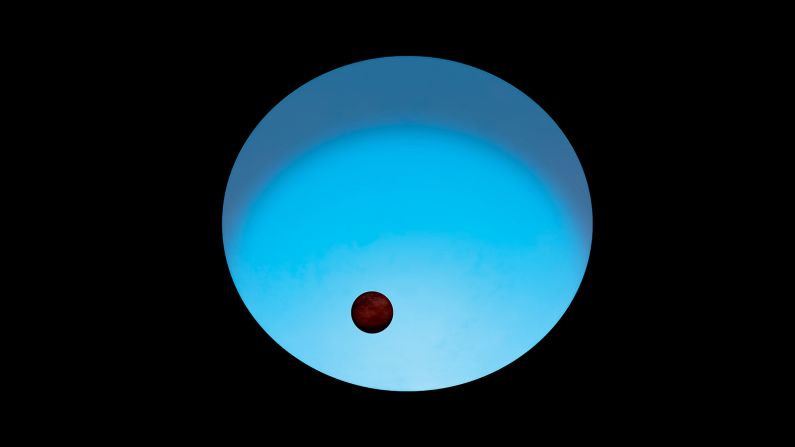

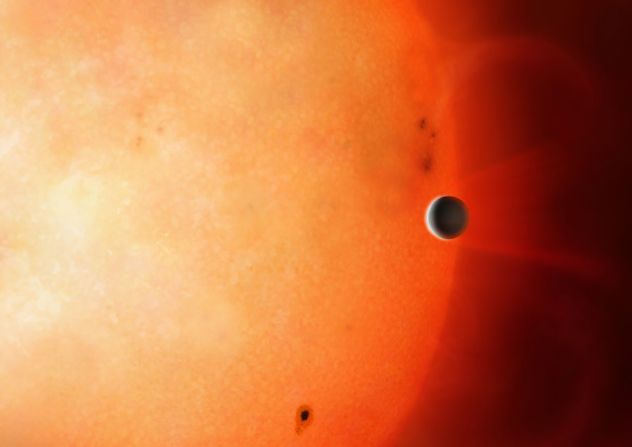

They also took into consideration each planet’s distance from its star – too close and the heat could vaporize any water, too far and any water could freeze.

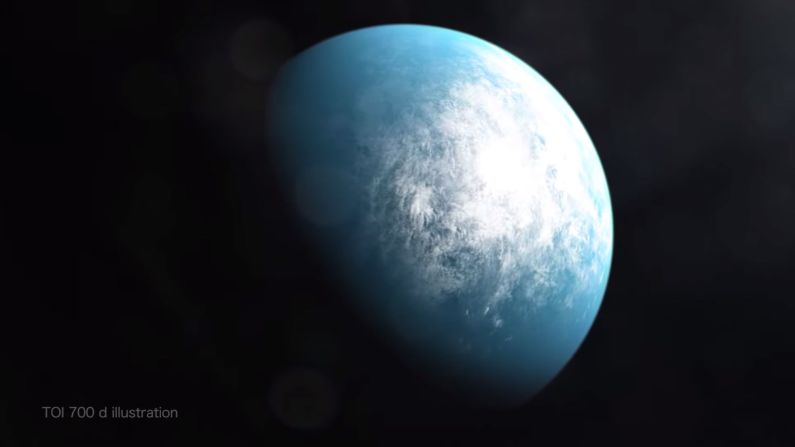

A habitable planet needs to be in the “just right” zone, or the so-called Goldilocks zone, to support liquid water on its surface.

Previous estimates of the number of habitable planets did not reflect how a star’s temperature and energy could be absorbed by its planets, said the NASA release. But this time, scientists were able to factor temperature into their analysis, thanks to additional data gathered by the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, which is charting a three-dimensional map of our galaxy.

“We always knew defining habitability simply in terms of a planet’s physical distance from a star, so that it’s not too hot or cold, left us making a lot of assumptions,” said NASA scientist and study author Ravi Kopparapu in the release.

“Gaia’s data on stars allowed us to look at these planets and their stars in an entirely new way.”

After calculating these factors, researchers used a conservative estimate that 7% of Sun-like stars could host habitable worlds. But the rate could be as high as 75%, scientists said.

NASA said it and other space agencies will continue to refine the estimate in future research, which will help shape plans for the next stages of exoplanet discoveries and telescopes. Currently, NASA’s TESS mission is the latest planet-hunter seeking out exoplanets.