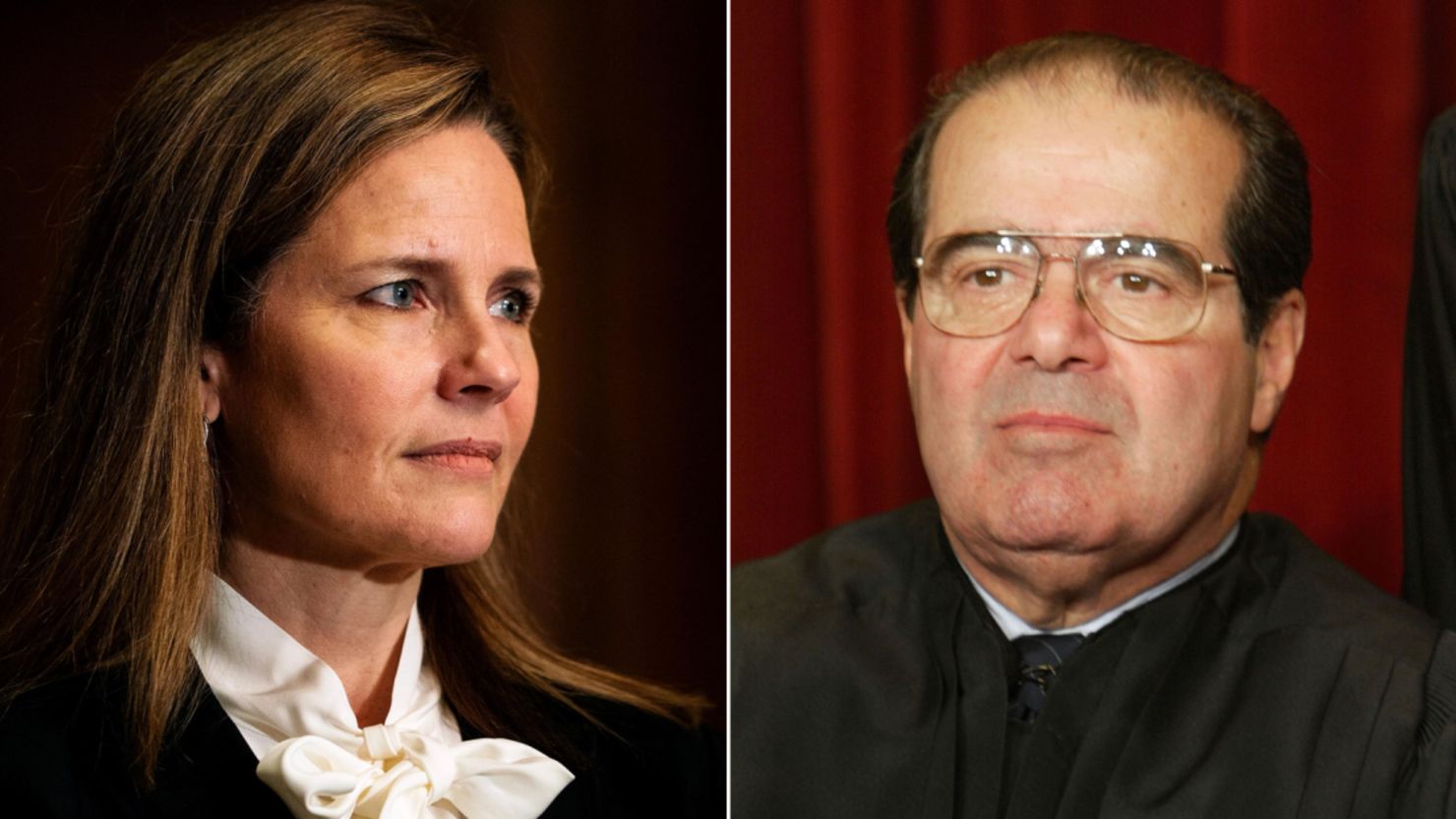

Antonin Scalia, the late Supreme Court justice known for his rigid conservatism and wicked turn of phrase, might appreciate that his specter lurks over the Amy Coney Barrett hearings.

It recalls one of his most memorable lines, as he took issue with a controversial standard for state aid to religious schools. He likened a decades-old rule – criticized by justices but never overruled – to “some ghoul in a late-night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in his grave and shuffles abroad … frightening the little children and school attorneys.”

Scalia was not a man of ambiguity. His views were black and white. Like President Ronald Reagan who appointed him to the high court in 1986, he was a defining figure who inspired legions of young conservatives who held him up as a model of judicial brilliance, including Barrett.

“I felt like I knew the justice before I ever met him, because I had read so many of his colorful, accessible opinions,” Barrett, who clerked for Scalia in 1998 and 1999, told the Senate Judiciary Committee on Monday. “More than the style of his writing, though, it was the content of Justice Scalia’s reasoning that shaped me. … A judge must apply the law as written, not as the judge wishes it were.”

At the White House on September 26, Barrett said of Scalia, “His judicial philosophy is mine too.”

Tuesday, Barrett emphasized, however, that she would not be a carbon copy of the late justice.

“I want to be careful to say that if I’m confirmed you would not be getting Justice Scalia, you would be getting Justice Barrett,” she said. “And that’s so because originalists don’t always agree and neither do textualists.”

Senate Democrats regard the Scalia philosophy as a path to the diminishment of individual rights and have warned of the continuing rightward turn of the Supreme Court. Scalia’s approach was the exact opposite, in fact, of that of pioneering civil rights Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whom Barrett would succeed.

During Scalia’s nearly 30-year tenure (1986-2016) he promoted “originalism,” a doctrine that looks to the framers’ understanding of the Constitution in the 18th Century.

In his view, that meant no abortion rights but a robust Second Amendment. He believed in strong executive power and little regulation of money in elections. He voted consistently against gay rights and angrily dissented when the justices in 2015 declared a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

Irreverence was his signature. “Get over it,” he told audiences for years after the 2000 Florida election case of Bush v. Gore. Scalia voted with the narrow majority in favor of Texas Gov. George W. Bush over Vice President Al Gore.

When Scalia refused to recuse himself from a 2004 case involving his friend and duck-hunting partner Vice President Dick Cheney, the justice wrote a 21-page public memo defending himself. In a university appearance around the same time, he closed his defense before students with the memorable: “Quack, quack.”

Scalia was famously friendly with Ginsburg – something several Republican senators noted on Monday. She said he was one of the few people who made her laugh. Ginsburg added of Scalia in one interview, “I love him. But sometimes I’d like to strangle him.”

He could never convince Ginsburg to adopt his judicial approach, but he influenced a generation of right-wing students. In the early 1980s as a law professor at the University of Chicago, Scalia was faculty adviser to the newly founded Federalist Society, begun by students at the Chicago campus and at Yale University. Scalia’s reputation grew as did the Federalist Society, and in the years after his 2016 death, his presence continued to loom, embraced by President Donald Trump.

Scalia’s wife, Maureen, has been invited to the White House on multiple occasions and was in the Rose Garden for the September 26 unveiling of the Barrett nomination.

In her academic writing before joining the bench, Barrett noted Scalia’s opposition to the Affordable Care Act, in 2012 and 2015 dissenting opinions.

Scalia wrote in the 2015 case, “We should start calling this law SCOTUScare,” referring to the acronym for the Supreme Court of the United States, as he contended the justices essentially rewrote the law to uphold it.

Also during that term ending in June 2015, Scalia’s last full session before his death, the justices declared a right to same-sex marriage.

Scalia derided the reasoning of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, particularly its opening references to liberty, and had this jab for the four liberals who formed the gay-marriage majority: “If, even as the price to be paid for a fifth vote, I ever joined an opinion for the Court that began: ‘The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity,’ I would hide my head in a bag. The Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.”

A new court has emerged since Scalia died four years ago, with two Trump appointees, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh. And now Judge Barrett, a protégé, stands ready to shift the court even more to the right, even more in Scalia’s image.