We’ve known for some time now that Greenland’s ice sheet is melting at an alarming rate.

Greenland lost more ice last year than in any year on record, and the melting has accelerated rapidly since the 1990s.

But in the context of Earth’s 4.5 billion-plus year history, melting in any one year or even a few decades amounts to the blink of an eye.

Whether the rapid disintegration we’re seeing on Greenland today compares to anything that has happened in the past is a question on which the science is not completely clear.

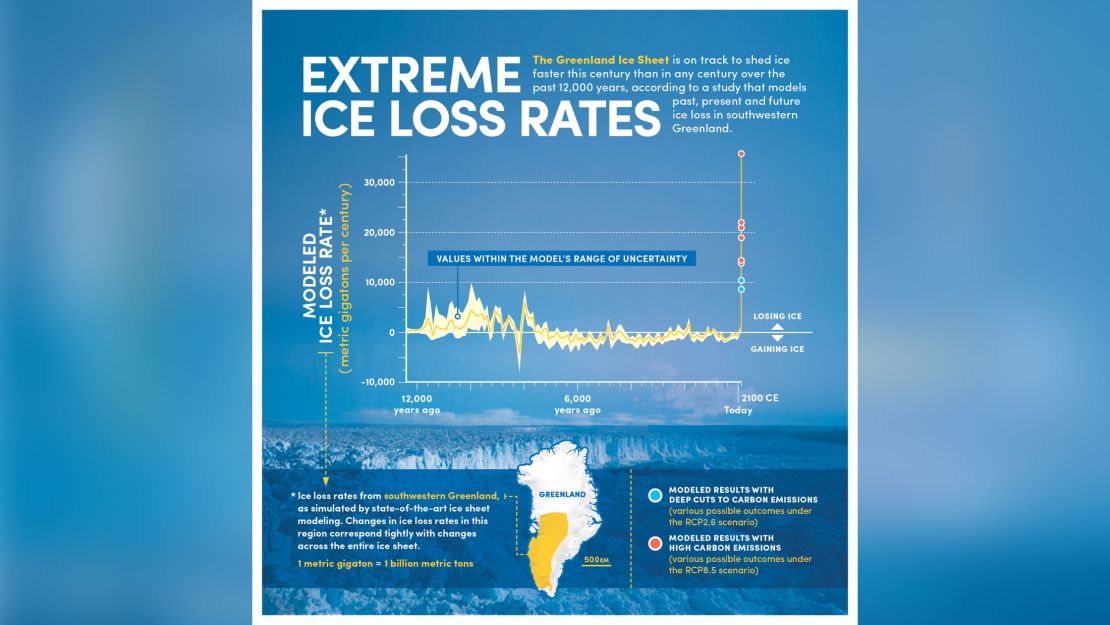

Now, a new study published in the journal Nature provides some answers, and it is not good news: The rate of melting we’re seeing today already threatens to exceed anything Greenland has experienced in the last 12,000 years.

Over the last two decades, Greenland’s ice sheet has melted at a rate of roughly 6,100 billion tons per century, a rate approached only during a warm period that occurred between 7,000 and 10,000 years ago.

“We know there’s a lot of year-to-year variability, so what we were interested in doing is capturing the more meaningful trends over decades and maybe up to a century,” said Jason Briner, a professor of geology at the University at Buffalo and the lead author of the study. “And when you do that, and think about the direction that Greenland is heading this century, it’s pretty clear we’re in quite anomalous times.”

The big difference between now and then? The influence of human activity.

The melting seen today is driven primarily by greenhouse gas emissions, whereas the warming that occurred thousands of years ago was a result of natural climate variability, Briner said.

How much Greenland melts going forward is up to us.

Under a scenario where humans continue to raise concentrations of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, Greenland’s ice loss could reach unprecedented levels, with more than 35,900 billion tons of ice potentially lost by the end of this century.

Right now, Briner says current melt rates track closely with this worst-case scenario.

However, if the world resolves to slash emissions enough so that global warming peaks around 2050, ice losses this century could be held to 8,800 billion tons – still a massive amount, but only enough to raise sea levels by about an inch, compared to the roughly 4 additional inches we can expect under a high-emissions scenario.

“Humanity has the knobs, and we can turn those knobs to decide what the ice sheet is going to do,” he said.

What happens to Greenland’s ice sheet and others around the globe will determine what the future holds for the millions of people living along the world’s coasts.

In terms of its potential to raise sea levels, Greenland is the world’s second most important ice sheet, behind only Antarctica.

Greenland’s ice sheet contains enough water to raise global sea levels by 24 feet. Over the last 26 years, melt water from Greenland has raised sea levels by 0.4 inches, and it is currently the world’s biggest contributor to sea level rise.

Melting from Antarctica, on the other hand, is currently responsible for 20-25% of global sea level rise, but is likely to surpass Greenland as the largest global contributor.

Antarctica holds enough water to raise sea levels by about 200 feet, and scientists have recently discovered alarming vulnerabilities in some of its most important glaciers.

A report last year from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that sea level rise is likely to exceed 3 feet by the end of this century if greenhouse gas emissions are not reigned in.

Rising seas are already causing problems in many coastal areas. And for places like New York and Shanghai, 3 feet or more of sea level rise could spell disaster.

Another recent study found that rising seas could cost the global economy $14.2 trillion in lost or damaged assets by the end of the century, and expose as many as 287 million people to episodic flooding, up from 171 million today.

“Clearly, the sea level rise from melting ice 12,000 years ago also affected people, but those people were much more widely spread out, and they didn’t have parking garages and integrated modern water systems serving millions of people,” said Richard Alley, a professor of geosciences at Penn State University who was not involved with the study published by Nature.

“These results say that human decisions about our energy systems are truly important in deciding how much sea level rise we face from melting of Greenland’s ice.”