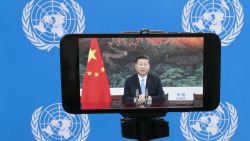

In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Tuesday, Chinese President Xi Jinping urged the world to “join hands to uphold the values of peace, development, equity, justice, democracy and freedom shared by all of us.”

After hailing China’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, Xi said Beijing wants to “continue to work as a builder of global peace, a contributor to global development and a defender of international order.”

It was a continuation of a role Xi has played at previous high-profile international meetings, as a defender of free trade and multilateralism, in contrast to an increasingly isolationist United States under President Donald Trump.

The difference between the two leaders was made neatly by Trump himself, who spent much of his UNGA speech attacking China, which he blamed for having “unleashed this plague onto the world.”

This is a dichotomy that has long existed, particularly as Xi has attempted to take advantage of Trump’s “America First” foreign policy to assert China’s dominance at international bodies like the UN.

But the rhetoric doesn’t always match the facts on the ground: for all Xi’s talk of free trade – at Davos and the UN – access to the Chinese market remains exceptionally difficult for many foreign companies. And while he may wax lyrical about world peace, under Xi, China is expanding its military and making increasingly aggressive moves in the South China Sea, in the Taiwan Strait, and along the country’s Himalayan border with India.

In addition, for all Xi’s apparent consensus building at the UN, the Chinese leader has shown he is unwilling to tolerate anything other than absolute loyalty at home.

Since Trump came to office, Xi has shored up control of the Communist Party, securing his rule indefinitely, and cracked down on all forms of opposition – be it in Hong Kong, Xinjiang or within the Party itself.

This week saw the jailing of prominent Xi critic Ren Zhiqiang for 18 years. The 69-year-old property tycoon and former senior party member was convicted on a raft of corruption charges, which appeared soon after he allegedly penned an essay criticizing Xi and calling the Chinese leader a “clown.”

The heavy sentence appears designed to send a message to other members of the Chinese elite: either fall in line or face the consequences.

This discrepancy between Xi’s international and domestic personas is perhaps a reminder that differences between the two leaders – and the political systems they represent – run deeper than mere style.

Trump is facing an increasingly rough road to reelection, and has spent much of the past four years fighting investigations, impeachment, and congressional opposition. Yet for the many problems with the US system exposed by Trump’s time in office, a democratically elected president ultimately does not and cannot wield as much power as his authoritarian counterparts. For all that Trump might wish to lock his rivals up when they insult him, he is constrained institutionally from doing so.

Which was perhaps why Xi could afford to be so statesmanlike at the UN, while Trump felt the need to go on the attack.

Holding China accountable

Though neither Trump or Xi mentioned each other by name, both appeared to have the other in mind.

In his speech Tuesday, Trump said the UN “must hold China accountable for their actions,” before listing a litany of alleged crimes by Beijing.

His remarks sparked an angry response from China’s ambassador to the UN, Zhang Jun, who called Washington’s handling of the coronavirus a “complete failure,” and said “it’s really time for some US politicians to wake up from their self-created illusions.” Zhang added the US “may wish to be great, but to be great you have to behave like a leader.”

Washington, however, is not the only government souring on China, and Xi’s ability to win over international audiences with his appeals to multilateralism and peace is starting to wane.

Beijing has faced increasing pushback from European powers over issues such as human rights abuses in Xinjiang, with French President Emmanuel Macron using his speech at the General Assembly to call for a UN mission to the far western Chinese region, where Beijing has allegedly detained hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs in recent years.

“Fundamental rights are not a Western idea that one could oppose as an interference … these are the principles of our organization, enshrined in texts that the member states of the United Nations have freely consented to sign and to respect,” Macron said.

“This is the reason why … France has requested that an international mission under the aegis of the United Nations go to Xinjiang in order to take into account the concerns that we collectively have on the situation of the Muslim Uyghur minority.”

While China may be able to block action on Xinjiang at the UN, Macron’s suggestion may concern Beijing more than Trump’s bombast, which Chinese officials are more than used to at this point.

For years after taking power, Xi was able to project a facade of normality internationally even as authoritarianism was on the rise back home. But now, that veneer may be starting to fade.