A gas on Earth has also been detected in the atmosphere of Venus. The “entirely surprising” discovery of phosphine could hint at unknown processes occurring on Earth’s “twin.”

Phosphine suggests the presence of life on Earth. And the idea of aerial life in the clouds of Venus is intriguing. But it’s not likely.

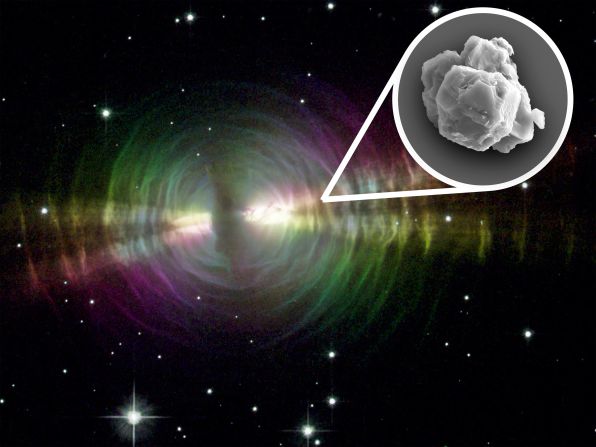

On Earth, phosphine is a flammable, foul, toxic gas produced by bacteria that doesn’t require oxygen – like those in swamps, wetlands, sludge or even animal guts. Its odor has been likened to decaying fish or garlic. It can also occur when organic matter breaks down.

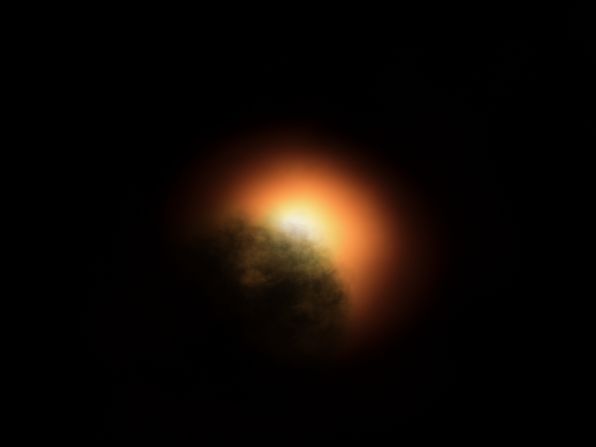

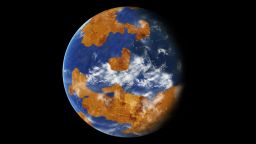

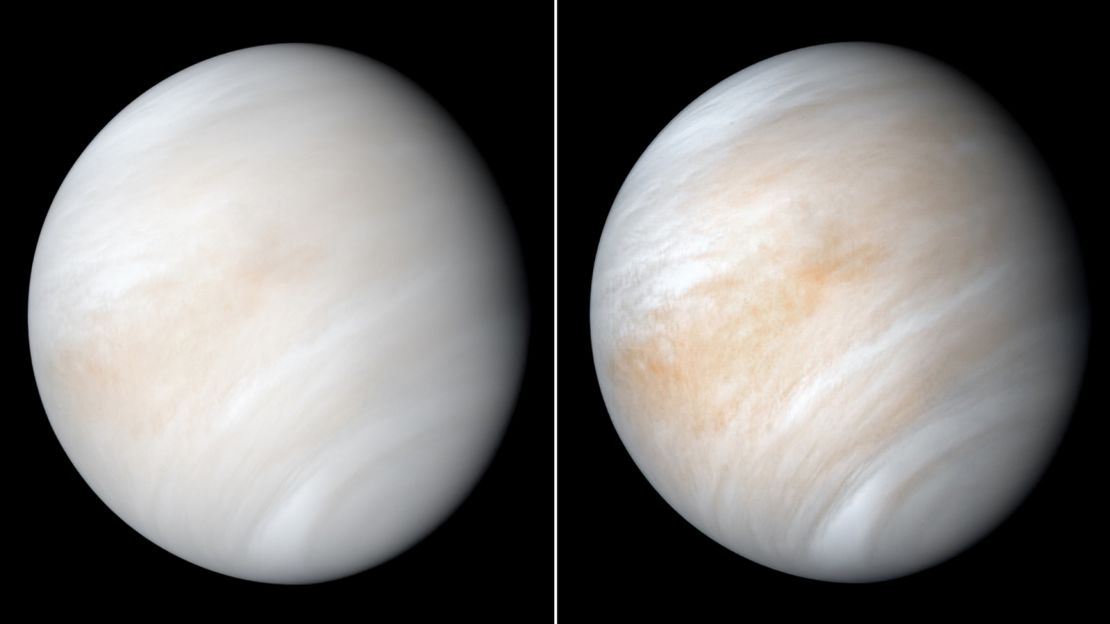

Venus is similar in size to Earth and often referred to as Earth’s twin, but it’s not really.

Venus is an unusual planet that scientists are still trying to understand. It’s our closest planetary neighbor, but it spins backward compared to other planets. The planet’s thick atmosphere helps to trap heat, and its surface is hot enough to melt lead.

Above its hot surface, which is 900 degrees Fahrenheit, the upper cloud deck that’s 33 to 39 miles above the planet’s surface is much more temperate. But Venus’ clouds are very acidic, which should quickly destroy phosphine. So how did it get there?

“Something completely unexpected and highly intriguing is happening on Venus to produce the unexpected presence of tiny amounts of phosphine gas,” said Sara Seager, study coauthor and astrophysicist and planetary scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in an email.

The study authored by Cardiff University professor Jane Greaves and her colleagues published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

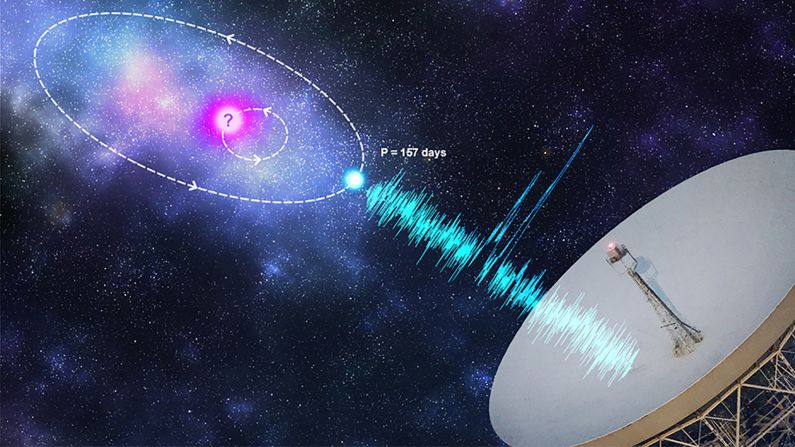

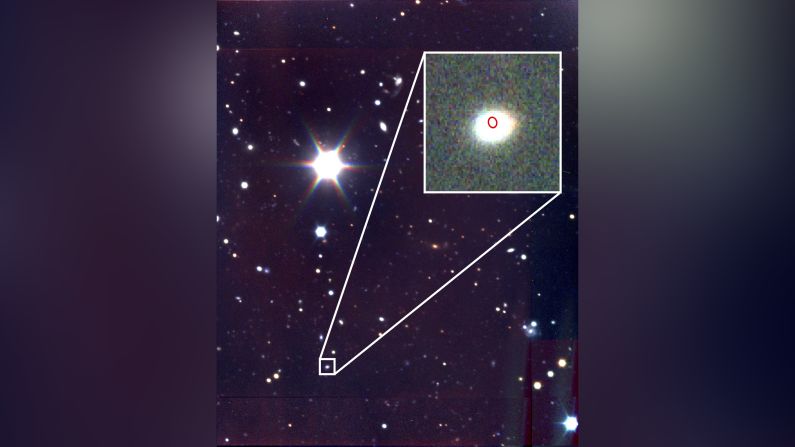

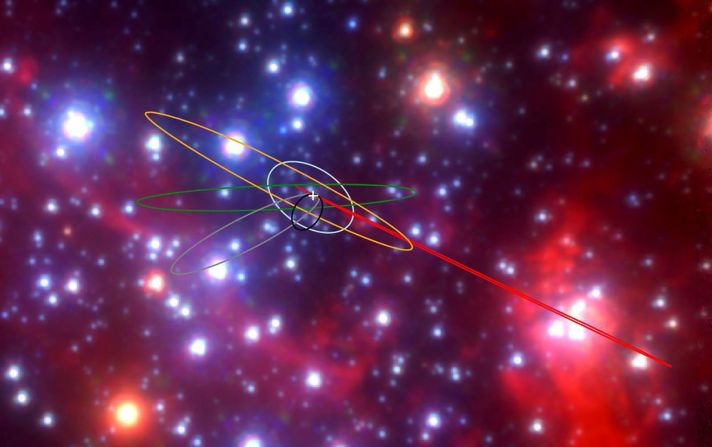

Researchers used the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii in 2017 and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in 2019 to study Venus. Their data revealed a spectral signature unique to traces of phosphine in the planet’s atmosphere. The scientists estimated 20 parts-per-billion of the gas is present in Venus’ clouds.

The research team considered surface sources like volcanoes, lightning, delivery via micrometeorites or chemical processes occurring in the clouds as potential causes. But the scientists weren’t able to determine how the phosphine was produced.

The researchers were left with rather extreme possibilities, Seager said.

“(One) is that some unknown chemistry is occurring in the Venus atmosphere, surface, or subsurface,” she said in an email statement. “We find this explanation tough to accept because (of) Venus’s temperature and pressure range and the fact that Venus has nearly zero hydrogensmean(s)phosphineis not the natural form of the element phosphorus. Instead phosphorus should be present as phosphates.”

Future observations could reveal the source, as well as modeling to show why the gas is present in the atmosphere. And a future potential mission that could sample the clouds and surface may also shed light on the source.

However, it could be an indication of chemical or geological processes occurring on Venus that haven’t been discovered yet or thought possible under the conditions on Venus.

Previously, a 2019 study, on which Seager was an author, suggested that phosphine may act as a biosignature for life if detected in “tremendous amounts” on rocky exoplanets. This large amount could be at an accumulated level that future telescopes, like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, could detect.

“Phosphine on Earth doesn’t exist outside of life’s production because, like on Venus, Earth’s environment is so very not favorable for phosphine production,” Seager said. “Because Venus is so close and bright our study found much smaller amounts than are predicted to be needed on an exoplanet.”

However, studying the atmospheres of rocky planets in our solar system provides a key test bed for trying to understand the atmospheres of exoplanets, or planets outside of our solar system, and if they could support life.

The research team will continue its search for the origin of the phosphine gas detected on Venus, as well as look for other unexpected gases in its atmosphere.

The discovery of phosphine on Venus elevates it to an area of interest worth exploring in our solar system alongside the ranks of Mars and “water world” moons like Enceladus and Europa, Seager said.

“Our hoped-for impact in the planetary science community is to stimulate more research on Venus itself, research on the possibilities of life in Venus’ atmosphere, and even space missions focused to find signs of life or even life itself in the Venusian atmosphere,” Seager said.