Editor’s Note: Thomas Balcerski teaches history at Eastern Connecticut State University. He is the author of “Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King” (Oxford University Press). He tweets @tbalcerski. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion at CNN.

With summer heating up, speculation surrounding Joe Biden’s vice-presidential selection is sizzling. Although the list of possible names has narrowed, all we know for sure is that the presumptive Democratic nominee will pick a woman and that four Black women are among the list of contenders.

This year’s Democratic vice presidential nominee will undoubtedly attract much scrutiny, given both Biden’s age and the state of the pandemic we continue to face.

History can reveal the strengths and the weaknesses of vice presidential picks – and help us decide how Biden’s selection ranks in comparison. Indeed, vice presidential selections have varied considerably across American history, with the successful verging on greatness and the not-so-successful bordering on villainy.

The best vice presidential choices have been drawn from the ranks of strong leaders with a track record of winning elections. They have overcome the inherent limitations of the office and creatively redefined their positions in some way. They have also often gone on to future electoral success.

By comparison, the worst vice presidential picks have revealed unforgivable foibles and committed truly heinous follies. Whether through treasonous action, racist conduct or corrupt behavior, bad picks have exhibited selfishness, complacency and an unseemly desire to enrich themselves – financially or otherwise. They typically do not again hold elected office.

Let’s start with the successful ones:

1. John Adams (1789)

In the first presidential election, John Adams received 34 votes from the Electoral College, making him the first Vice President of the United States (before the Twelfth Amendment, electors were each given two votes to cast, with the person obtaining the most votes becoming president and the second most votes becoming vice president). Adams helped to define the role, fulfilling his constitutional duties of presiding over the US Senate and breaking ties as necessary.

He also yearned for greater responsibilities and, in the process, learned an enduring truth about the office – its obscurity. To his wife Abigail Adams, he famously complained: “My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

Still, Adams faithfully served as vice president to George Washington for eight years. In 1796, after Washington announced his retirement, Adams succeeded him as the nation’s second president. He pioneered the path for future vice presidents (Biden among them) to run for president.

2. Theodore Roosevelt (1900)

Theodore Roosevelt might never have become president without first serving as vice president. Ironically, the energetic Roosevelt was selected as William McKinley’s running mate to sideline the young upstart from New York. McKinley loyalist Ohio Sen. Mark Hanna strongly objected to the selection. “Don’t any of you realize there’s only one life between this madman and the White House?” he asked.

Roosevelt himself was initially nonplussed by the job and did little to support the McKinley administration. The office was “not a steppingstone to anything except oblivion,” he scoffed. But in 1901, McKinley was assassinated, and the “madman” suddenly became president.

As president, Roosevelt championed progressive legislation and an aggressive foreign policy. He advocated regulating so-called “bad” trusts, notably railroad and meatpacking corporations, which earned him the nickname of “Trust-Buster.” At the same time, he strengthened the US Navy, oversaw the building of the Panama Canal and negotiated a peace accord between Japan and Russia. In hindsight, his nearly eight years in office signaled the start of the modern presidency.

3. George H.W. Bush (1980)

When George H.W. Bush beat out former California Gov. Ronald Reagan in the Iowa caucuses, he famously declared his campaign to have “the Big Mo,” his shorthand for “momentum.” But Reagan beat Bush in New Hampshire and went on to take the nomination. Then, like now, the question of Reagan’s age (he turned 69 during the campaign) loomed large.

At first, some Republicans speculated about a “dream ticket” that consisted of Reagan as president and former President Gerald Ford as vice president. But when Ford suggested to television anchor Walter Cronkite that their relationship would need to be a “something like a co-presidency,” Reagan blinked. Instead, Reagan chose his former rival Bush.

Bush proved an inspired choice, as he dedicated himself to campaigning for Reagan’s election. He stood ready to assume the office during the assassination attempt on Reagan’s life in 1981. In his two terms in office, he chaired special task forces, toured Western Europe and Asia and contributed to de-escalation efforts with the Soviet Union. Bush’s election as president in 1988 was also the last time a vice president successfully made the leap to the Oval Office.

Honorable mentions: Calvin Coolidge (1920), Harry Truman (1944) and Lyndon Johnson (1960)

By contrast, these three vice presidential picks stand out as truly awful leaders in American history:

1. Aaron Burr (1800)

At first, the selection of Aaron Burr as Thomas Jefferson’s running mate seemed a happy, if unimportant choice. “The Matter of V.P – is of very little comparative Consequence,” Jefferson wrote one correspondent. But when the vote of the Electoral College produced a tie between Jefferson and Burr – possible under the provisions of the Constitution prior to the Twelfth Amendment – chaos ensued.

The House of Representatives met to decide the election. After over 30 rounds of balloting, Jefferson was at last chosen, no thanks to Burr, who refused to withdraw from the race or publicly support Jefferson. As vice president, Burr proved himself a rogue agent. On July 11, 1804, the sitting vice president killed former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in a duel in Weehawken, New Jersey.

In 1807, having not been reelected as vice president, Burr was charged with treason, when General James Wilkinson alerted Jefferson of a plot to invade Mexico and form a separate southeastern confederacy. However, Chief Justice John Marshall acquitted Burr due to a lack of concrete evidence against him (the case was extensively cited in this month’s Trump v. Vance decision). Nevertheless, a disgraced Burr left the United States for Europe in 1808.

2. Andrew Johnson (1864)

During the wartime election of 1864, the Republican Party, operating under the banner of the National Union ticket, swapped out sitting Vice President Hannibal Hamlin of Maine for Sen. Andrew Johnson of Tennessee. A southerner, Johnson was picked to present a nationally balanced ticket alongside President Abraham Lincoln. Michigan Sen. Zachariah Chandler later complained that Johnson was “too drunk” to perform his duties at his own vice presidential inauguration.

Lincoln was assassinated less than six weeks into his second term, and the untested Johnson became president. When the Civil War ended, Johnson enacted a lenient form of Reconstruction that undercut efforts to secure rights for the newly freed African Americans in the South. By 1866, Johnson had issued more than 1,200 pardons to former Confederates, outraging Republicans.

In 1868, Johnson was impeached for violating the Tenure of Office Act after firing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton without first obtaining congressional approval. However, when Johnson was later tried by the Senate, seven Republicans defected, and he escaped removal by one vote. He remains only one of three US presidents to endure an impeachment trial.

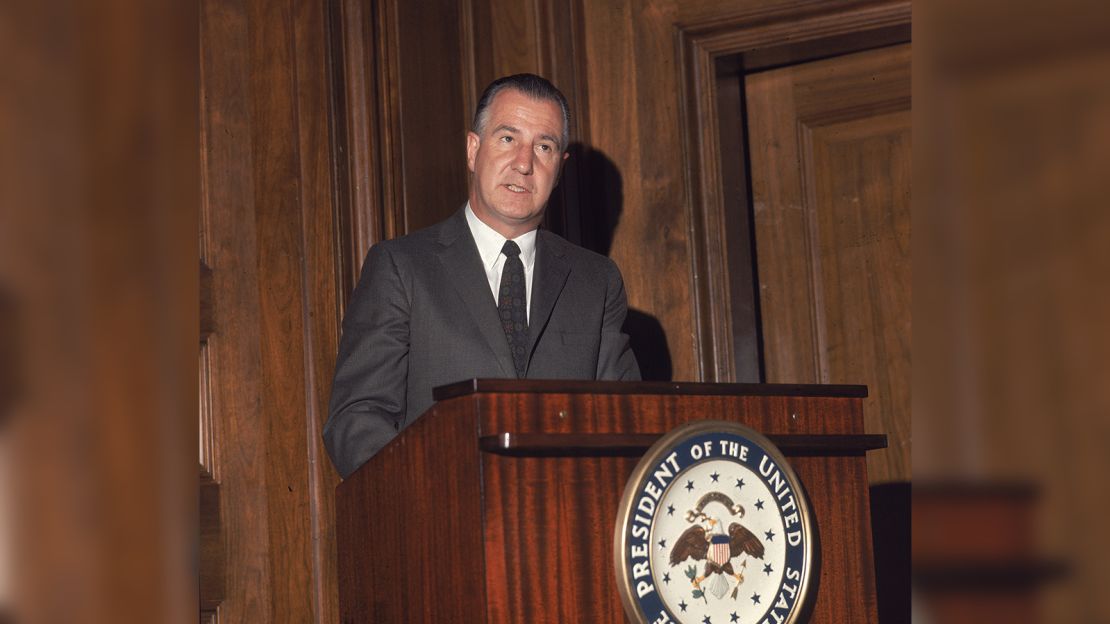

3. Spiro Agnew (1968)

The list of US vice presidents features few more infamous than Spiro Agnew. Richard Nixon selected him in 1968 for his tough law and order stance and what Nixon referred to as his “quiet confidence.” More importantly, Agnew appealed to the conservative wing of the Republican Party.

As vice president, Agnew was known for his acerbic retorts, often featuring a dizzying degree of consonants (his cry against “the nattering nabobs of negativism” lives in infamy). His incendiary comments against college students and the media likewise earned him loyal supporters among conservatives.

But Agnew was also palpably corrupt. In early 1973, he was accused of taking bribes for construction contracts in Maryland, and, by the fall, he resigned as vice president. The unprecedented move paved the way for Gerald Ford to replace him as vice president. Nixon’s resignation a year later (also a first) unexpectedly made Ford the 38th president.

Dishonorable mentions: John C. Calhoun (1824), James S. Sherman (1908), Richard Nixon (1952)

Whomever Biden picks should be someone with the potential to learn from the successes – and failures – of her predecessors and who is prepared to assume the role of president in her own right. The future of the country may depend on it.