“I’m Fanny Smith. I was born on Flinders Island. I’m the last of the Tasmanians.”

The audio?is scratchy and distorted, sounding at times like it is being spoken through a wall. Yet the voice speaking is high and proud, with long, stretched syllables in English. When she breaks into song, in her native language, it is half chant, half bluesy-spiritual.

Smith?was born?on the Australian island of Tasmania, in December 1834, to the Palawa people, an Indigenous population that had lived on the land for at least 34,000 years.

By the time she died in 1905, Smith was the last native speaker of her people’s language.

It was one of more than 250 distinct languages spoken on the Australian continent when Europeans began arriving in the 17th and 18th centuries.?Since then, colonial rules systematically stripped Indigenous peoples of their languages through English-only education policies and discriminatory practices, causing deep-rooted issues that held communities back socially and economically, and fractured their identities.

The Black War

When Europeans first?invaded?Tasmania in 1803, there were between 4,000 and 10,000 Indigenous people living on the island.

By the middle of the century, this had dropped to the low hundreds, with thousands having been exterminated by the “Black War,” a campaign,?beginning in the 1820s,?by European settlers to push the Indigenous Palawa people off the newly settled territory.

Survivors were forced to move to Flinders Island, a remote outpost that previously served as a prison colony. On the Island, Indigenous people were encouraged to assimilate, take English names and adopt European dress.

That was where Smith was born in the 1830s, one of a community of around 100 people?living on the island.

In 1847, the camp at Flinders Island shut down amid growing controversy. Smith was among a few dozen other surviving Indigenous Tasmanians who moved to Oyster Cove, south of Hobart, where years later she met her husband, William Smith, an English ex-convict transported to Australia for stealing a donkey.

In 1876, Fanny Smith petitioned the government to recognize her as the last surviving Tasmanian Aboriginal. She received a parliamentary grant of £50 and a 300-acre piece of land, as a form of compensation for the near extermination of the island’s Indigenous population.

The recognition of Smith, and before her a woman called?Truganini, as the “last Tasmanians” sparked a belated desire?among some Whites?to preserve the island’s culture and language – if not its people.

In 1899, a few years before her death, Smith traveled to Barton Hall, a stately home in the swanky Hobart suburb of Sandy Bay.?A photo?from that day shows her standing in the house’s garden, her face inches away from a phonograph trumpet connected to a wax cylinder recording device operated by Horace Watson, of the Royal Society in Hobart.

Watson recorded Smith twice, talking about her life and singing in her native language. She cried when she heard the recording played back to her, reminded of her mother’s voice.

Yet the experience was not entirely a sad one. Smith sang hymns and traditional songs for Watson, and translated one of the songs she sang into English:

It’s spring time,

The birds are whistling, the spring is come,

The clouds are all sunny,

The fuchsia is out at the top, the birds are whistling, everything is dancing,

Because it’s springtime, everything is dancing,

Because it’s springtime.

“This record was made for me by Fanny Smith in 1903,” Watson says at the end of one of the recordings. “We had a real excellent time here.”

When Smith died two years later, the Tasmanian languages died with her. This pattern would play out again and again across Australia in the 20th century, as the rights of Indigenous people were trampled and their languages and culture increasingly marginalized or assimilated.

Language loss

It’s a cliche that we do not fully appreciate what we have until it’s gone, but the mass death of Australian languages has proven to be the perfect laboratory for studying language decline and the effects it has had on Indigenous communities.

Decades of work by researchers has provided important findings into how the loss of language feeds into health, economic and education outcomes, and made the case for preserving and bolstering minority languages.

In Australia, Indigenous people are twice as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to have a severe or profound disability, and more than six times as likely to live in social housing. The unemployment rate for Indigenous people is also 4.2 times the national average.

In Canada, too, a government survey found First Nations and Inuit people lag far behind non-Indigenous populations “as measured by most major indicators of health.”

“Indigenous health is widely understood to also be affected by a range of cultural factors, including racism, along with various Indigenous-specific factors, such as loss of language and connection to the land, environmental deprivation, and spiritual, emotional, and mental disconnectedness,” researchers Malcolm King, Alexandra Smith and Michael Gracey argued in a 2009 paper for The Lancet. “Language is crucial to identity, health, and relations. It is especially important as a link to spirituality, an essential component of Indigenous health.”

Douglas Whalen, a speech and language expert at the City University of New York,?said that those communities which retained their Indigenous languages showed better results across a host of health metrics, from?“suicide to diabetes.”

“Not that I believe that language has magical properties – although some communities do – it’s just that it reestablishes a sense of community and connectedness that is currently lacking for many people,” he said.?“Language and culture are very tied together. I think language still has a special place because you can connect it to any cultural practice, everybody recognizes it as part of their cultural heritage.”

Dianne Biritjalawuy Gondarra, a Yolngu woman from Arnhem Land, on the northern tip of Australia, said that “culture is a shadow, it’s something that follows your everywhere, and part of culture is language, which connects me back to my land.”

“It disconnects a person if you don’t have your language,” Gondarra said. “You feel it, that loss.”

Michael Walsh, a researcher at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), said that in his work on language revival,?working with people rediscovering their Indigenous languages,?“what always struck me very forcibly was the way an individual would say that getting their language back had changed their life.”

“We’ve got the gloomiest statistic of the highest level of youth suicide among Indigenous people in the OECD,” he added.?The hope is that by improving access to Indigenous languages and culture, this can help connect people with their identity and stave off or at least reduce mental health problems.

“If language can be used to arrest this level of suicide obviously it’s going to be a good thing,” he said.

Cut off from information

Many Indigenous language speakers also find it hard to access information, with key education and health materials only available in English – exacerbating the gap between outcomes for Indigenous Australians and Whites.

“Basic primary underlying knowledge is unavailable to them,” said Richard Trudgen, director of Why Warriors, a Northern Territory-based Indigenous rights group. “This is why nothing is working, this is why the gap never closes and it gets wider.”

While younger Indigenous people may learn English through school,?educational outcomes?are worse?in Indigenous communities compared to White ones,?they people still lack access to resources in their native tongue?and may struggle to understand more complex materials in a second language.?In the Yolngu community where Trudgen works, in northeast Arnhem Land, a lack of access to information in their own language, as well as the tools to translate from English to Yolngu, leaves people in a “paralyzed learning state,” Trudgen writes in an upcoming report, a draft of which was shared with CNN.

“They cannot self-learn … and cannot productively control their lives becoming just like dry leaves on a tree that fall to the ground,” he said.

“When Yolngu look around at their own world they see their own economic, legal and governance structure which they understand,” Trudgen continues. “But the Balanda (mainstream Australian) economic legal and governance structure is just a blur of confusion. This seems to be a whole level of knowledge that the Balanda education system has not given them access to or has locked away from them like the roots of the tree in the ground.”

Gondarra, who works with Trudgen on a number of projects, said that without formal education in their own language, young people are left with a denuded version of it, with more complex topics always discussed in English.

“They’re left thinking (the language) is dumb and stupid, but it’s dumb and stupid because it’s been dumbed down,” she said. “They’re not learning the high and old language, the economic and academic language.”

A lost pearl

Whalen, the CUNY expert, said that “when you talk to people from Indigenous communities” about the value of language in promoting general health and other outcomes, “they are completely unsurprised.”

Testifying before an Australian parliamentary inquiry in 2012, Yurranydjil Dhurrkay, a woman from Galiwin’ku, an island off the coast of Arnhem Land,?said that?“our language is like a pearl inside a shell. The shell is like the people that carry the language. If our language is taken away, then that would be like a pearl that is gone. We would be like an empty oyster shell.”

For a large number of Indigenous Australians, however, these pearls have been actively stolen. Only 13 of the 100 or so Indigenous languages spoken across Australia are acquired by children, vital for them to survive into another generation,?according to AIATSIS.

Most languages are spoken only by a handful of elders who are rapidly dying out – joining Fanny Smith as the last speakers of their native tongues. In the past, languages were often viewed in Darwinian terms, the survival of the fittest. But more recent research has shown that by and large, languages do not die out, they are killed.

After Europeans invaded the Australian continent in 1788, scant effort was made to learn Indigenous languages, except by a handful of colonists, and White and Indigenous communities largely lived separately. When they did overlap, Indigenous peoples were often treated brutally, forced into slavery or menial labor, or massacred.

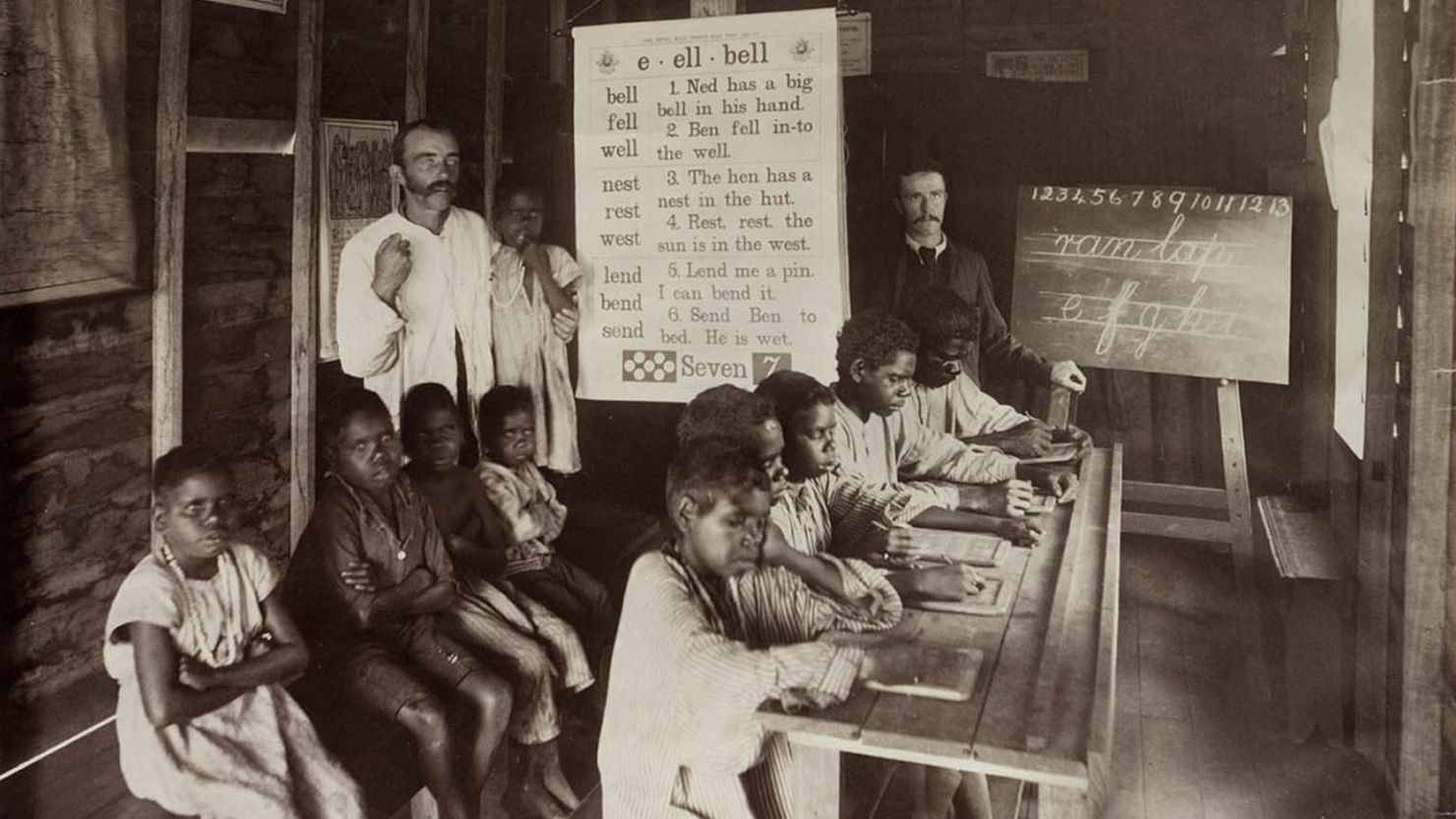

As White Australians took over more and more of the continent, Indigenous peoples could no longer be ignored, and efforts were made to assimilate them into colonial society. Beginning in the late 19th century and lasting until 1970, Indigenous children were routinely removed from their families and placed in White households or institutions, stripped of their culture and language.

Those not of the “stolen generations” were often little better off. Schools and missions across the country were ordered to stop using Indigenous languages and switch to English.

“They were told don’t speak your language, don’t practice your culture, or your children will be taken away from you,” said Letetia Harris, a Wiradjuri language teacher in Wagga Wagga, in New South Wales. “The people who are the victims or the children of the victims live with that and there is not one Aboriginal person who is not affected by stolen generations or that fear (of having their children taken).”

The tide has slowly been turning in favor of language revival, or at least preservation, since the 1960s, writes Indigenous languages researcher Laura Rademaker. In 1973 – after decades of work by Indigenous educators and activists – the government reintroduced mother tongue education at select schools. However, this program has not been without setbacks, and many communities still struggle to access key materials, Trudgen said.

Often it is not “until the people are basically wiped out and have lost all their language and start to learn English” by necessity, he added, that they finally gain access to vital information, on subjects such as germ theory, dealing with the government, and legal matters. This is not a failure of the language, Yolgnu for example can express and discuss these concepts as well as English, but in education and resources available.

Trudgen said that many English-speakers unconsciously believe that is the only language through which people can acquire knowledge, when Indigenous languages are fully capable of being used to teach complex topics.

“The mainstream mindset is that the people are primitive, their languages are primitive, we’ll just force them into school and tell them they all need to speak English,” he said. “A hundred years ago they whipped Aboriginal people for speaking their languages – we’ve gone from that to a more subtle form of whipping, where we just won’t use their languages.”

Slow progress

Since the 1970s, progress in revitalizing – and in some cases reviving – Indigenous Australian languages has been slow, but it is occurring.

Walsh, the AIATSIS researcher, said revitalization work can sometimes be harmed by a focus on the “doom and gloom around Australian languages,” as this can encourage defeatism and make it hard to rally support for at-risk languages.

“In fact, a lot of languages are vastly ahead of where they were 20 years ago and things are really gathering pace,” he said, pointing to successful efforts to reintroduce Wiradjuri?to schools in the region.

“In monolingual Australia, for there to be 5,000 people learning Wiradjuri, that’s just off the scale. Twenty-five years ago, if there were 15 people learning a language we would be delighted.”

Even symbolic use of languages – such as translating road signs or government announcements, or broadcasting snippets on TV – can have a major effect, Walsh added.

Whalen, the CUNY expert, agreed. “The goal does not have to be complete fluency, having the Indigenous language spoken on the street every day,” he said. “Lots of smaller uses and more constrained uses are still valuable.”

Growing up in the 1960s, Cheryl Penrith only knew a handful of Wiradjuri words. Elders at that time were careful not to speak the language in front of children, and many in the community had been traumatized by experiences of the stolen generations.

“One of the reasons people were removed from their families was to stop people talking language,” she said. “People were really deterred from speaking language.”

As an adult, Penrith, who lives in Wagga Wagga, took a Wiradjuri course, part of the state-wide language reclamation project led by Indigenous elders and activists.

“It has been really empowering for us, it connects us to country,” she said. “Language can really connect you to place and your identity.”

Recent years have seen a mini-renaissance in Indigenous culture and art, with projects such as NoongarPedia, the first Wikipedia site in an Australian language, translations of Shakespeare, and more programming for Indigenous language content on radio and television.

Revival movements for endangered or even dead languages are also underway across the country, including in Tasmania, where a composite language – Palawa kani – drawn from historical sources has gained some traction in recent years.

While mother tongue teaching and language revival is important worldwide, it is of particular importance in Australia, where Indigenous culture and language is deeply connected to the land and relies a great deal on oral storytelling. Many members of the stolen generations have spoken of how being taken away from their family and culture has left them disconnected to the land as well, unsure of where they belong and who they are.

Gap remains

More than 100 years after Fanny Smith’s death, Australia has changed in a way that would have been unimaginable for her generation. A White settler society has transformed into a modern, multicultural and multiracial country.

But despite that progress, Indigenous people have, to a great extent, remained on the fringe, cut off from advances and still subject to discrimination and racism.

Unlike other Commonwealth countries such as New Zealand and Canada, Australia still doesn’t have a treaty between its government and its Indigenous people. Indigenous people are also vastly overrepresented in crime and prison statistics, and those regarding deaths in custody.

Indigenous rights in Australia have been thrust back onto the political agenda with global protests for racial justice in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by US police officers. Marches held across the country featured tens of thousands of people of all races, who connected the American issue to that felt by Black people in Australia, with one sign reading “same story, different soil.”

Echoing a key slogan of the US protests, Trudgen, director of Why Warriors, said that the “dominant culture needs to take their knee off the neck of Indigenous people in Australia and let them breathe intellectually.”

“This is a prime opportunity now to take it to a different level,” he added.

Harris, the Wiradjuri language teacher, took part in Black Lives Matter marches in Wagga Wagga. She was skeptical about White Australia’s willingness to change and address longstanding problems of discrimination and marginalization, but nevertheless saw the protests as a step forward, with both Indigenous and other Australians joining together.

“There’s still a heck load of racism in Australia,” Harris said. “The only thing we can do is walk, and keep lifting up our people, and welcoming those who are willing to open their eyes to us.”

James Griffiths a senior producer for CNN Worldwide and author of the upcoming “Speak Not: Empire, identity and the politics of language” from Zed Books/Bloomsbury.