Editor’s Note: We are publishing personal essays from CNN’s global staff as they live and cover the story of Covid-19. Mirna Alsharif is a news assistant in the New York bureau.

Before the pandemic, I knew exactly how I would spend Ramadan. I would avoid food, water and swearing – which I unfortunately do often – for up to 16 hours a day, all while longingly staring at my colleagues enjoy their morning coffee at work. Maybe have “iftar” to break the fast with my uncle and his family at his apartment in Queens on the weekends. And I’d definitely take some time off to visit my parents and sister in Dubai to enjoy the holy month together.

Coronavirus Diaries

I was looking forward to the central community message of Ramadan – to cooking and baking with my mom, attending evening “taraweeh” prayers at our local mosque and hosting huge iftar parties at my parents’ house like we did every year.

But when New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued the stay-at-home order on March 22, I realized that the chances of any of that happening were slim to none.

Almost overnight, New York City became something I’ve never seen it be before – a ghost town. Soon after, it also became the epicenter of the coronavirus in the United States.

By the time Ramadan started on April 24, I’d been working from my 319-square-foot studio on the Upper East Side for a little over a month. I’d originally thought we’d be out of lockdown in time for the fast, but it quickly became clear to me that this Ramadan was going to be different.

I was going to spend a month that is all about community, perfectly alone.

I would have “suhoor,” the meal before sunrise, by myself. I would pray five times a day by myself. I would break fast at sunset by myself.

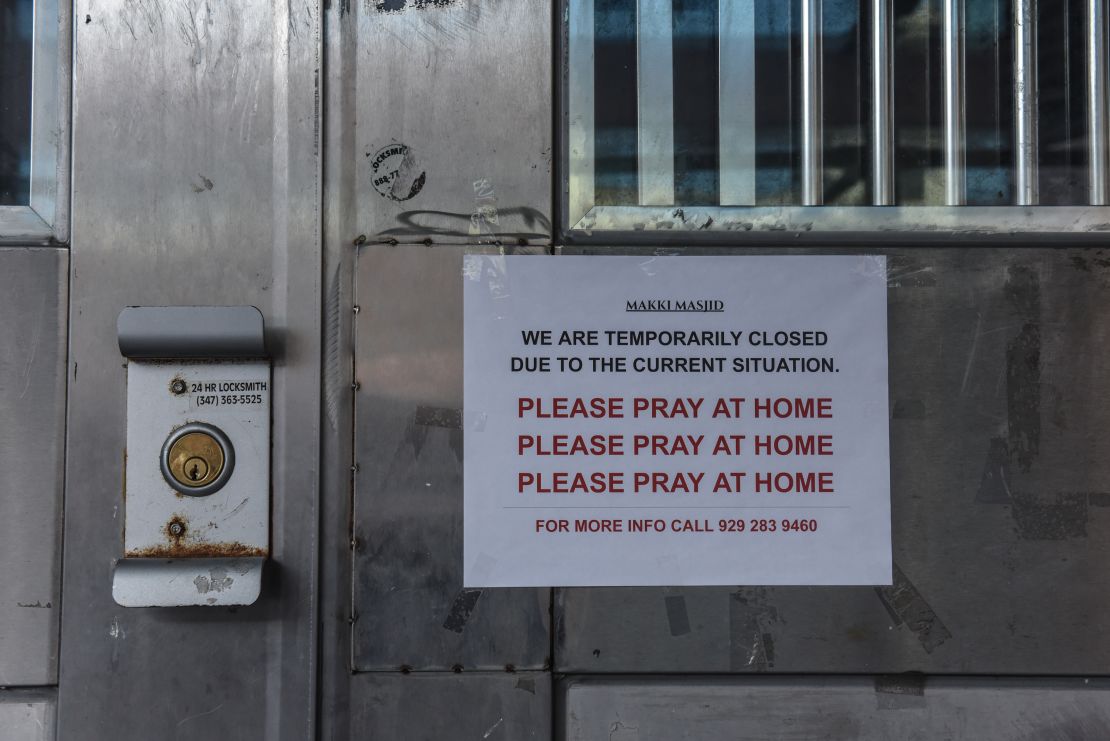

There would be no overseas travel to see my family, no shoulder-to-shoulder congregational taraweeh prayers at my neighborhood mosque or family gatherings at my parents’ house where I could eat “kunafa” soaked in sugar syrup or “atayef” filled with whipped cream.

Traditions have been replaced by Zoom calls with my family and friends across the US, Dubai and my mother country, Egypt. While the calls sometimes soften the blow of my isolation, they also serve as a reminder of how far away I am from my loved ones this year.

“Are you sure you’re OK? Are you eating enough?” my mom asks me every time we talk. I wouldn’t dare say anything other than yes; the last thing I want is for her to know how much I’m struggling right now. Or how much takeout I’m ordering.

But while the pandemic has shown me just how fickle life is, how almost anything can change without a moment’s notice, the fast has given me perspective and reminded me to be thankful for everything I have while I still have it.

There are so many people who have lost their lives to the coronavirus; more than 15,000 in New York City alone. There are over 20 million health care workers on the front lines across the US fighting every day to save lives. And there are so, so many who have lost their jobs and may be struggling to put food on the table.

This month, I’m thinking about my friend, Mohamed Madboly, who started his own food cart business at 19 years old and parked it right outside the New York Institute of Technology, where he was also a student. The pandemic has forced him to shut down the business he worked five years to get off the ground, but this Ramadan he’s extra thankful because his elderly father seems to be recovering from Covid-19. Mohamed also tested positive and continues to struggle with symptoms, like having no sense of smell, all while observing the fast.

I’m also thinking about Naoual Elidrissi, an essential worker who lives only 10 minutes away from her elderly parents in Queens but wouldn’t dare visit them during Ramadan out of fear of passing on the virus.

While the pandemic has taken a lot from me – and so many others – during this holy month, it has given me time that I didn’t have before to pray the daily five prayers on schedule, to reflect on just how fortunate I am and to get to the root of what Ramadan is truly about beyond all the pomp and circumstance: Gratitude.

I am grateful. For my health that I often take for granted. For the food I have access to. For my family and loved ones. For the first responders and health care workers taking risks on the front lines for the greater good.

This year, I’m not surrounded by my colleagues and the scent of their countless cups of coffee or visiting family and partaking in Ramadan tradition. Instead, I’m tucked away in my tiny, fifth-floor walk-up apartment in complete isolation.

But at sunset every single day when I take my first sip of water, I’m more conscious than ever before that I have clean water to drink, good food to eat and a roof over my head – and that’s more than enough for now.