Editor’s Note: Roxanne Jones, a founding editor of ESPN Magazine and former vice president at ESPN, has been a producer, reporter and editor at the New York Daily News and The Philadelphia Inquirer. Jones is co-author of “Say it Loud: An Illustrated History of the Black Athlete.” She talks politics, sports and culture weekly on Philadelphia’s 900AM WURD. The views expressed here are solely hers. Read more opinion on CNN.

Even in grade school, I longed to tell stories the stories of black folk – about our lives, our loves and the fears and frustrations we lived with every day. I wanted to give a voice and a face to the amazing people I encountered every day who mostly felt invisible or marginalized in America.

I imagined writing about my fun-loving grandfather, a proud veteran, who served this nation despite extreme racism and hatred he confronted his entire life – on and off the battlefield. I dreamed of writing a book about my beautiful Aunt Rosie, who made the best potato salad I’ve ever tasted and had the rarest of gifts: making everyone around her feel deeply loved.

But it was after my father was murdered that I vowed to study hard, go to college and study journalism – no simple goal for the daughter of a now-single mom struggling to raise three kids. But, I was determined. It was inexplicable to me that neither my dad’s death – nor the deaths of other black and brown people I knew – ever made headlines, or, in my father’s case, never even led to an arrest.

So, at 10-years-old, I made a plan.

Problem was, I had never met a journalist, let alone one who looked like me. Honestly, most people laughed when I told them my plans.

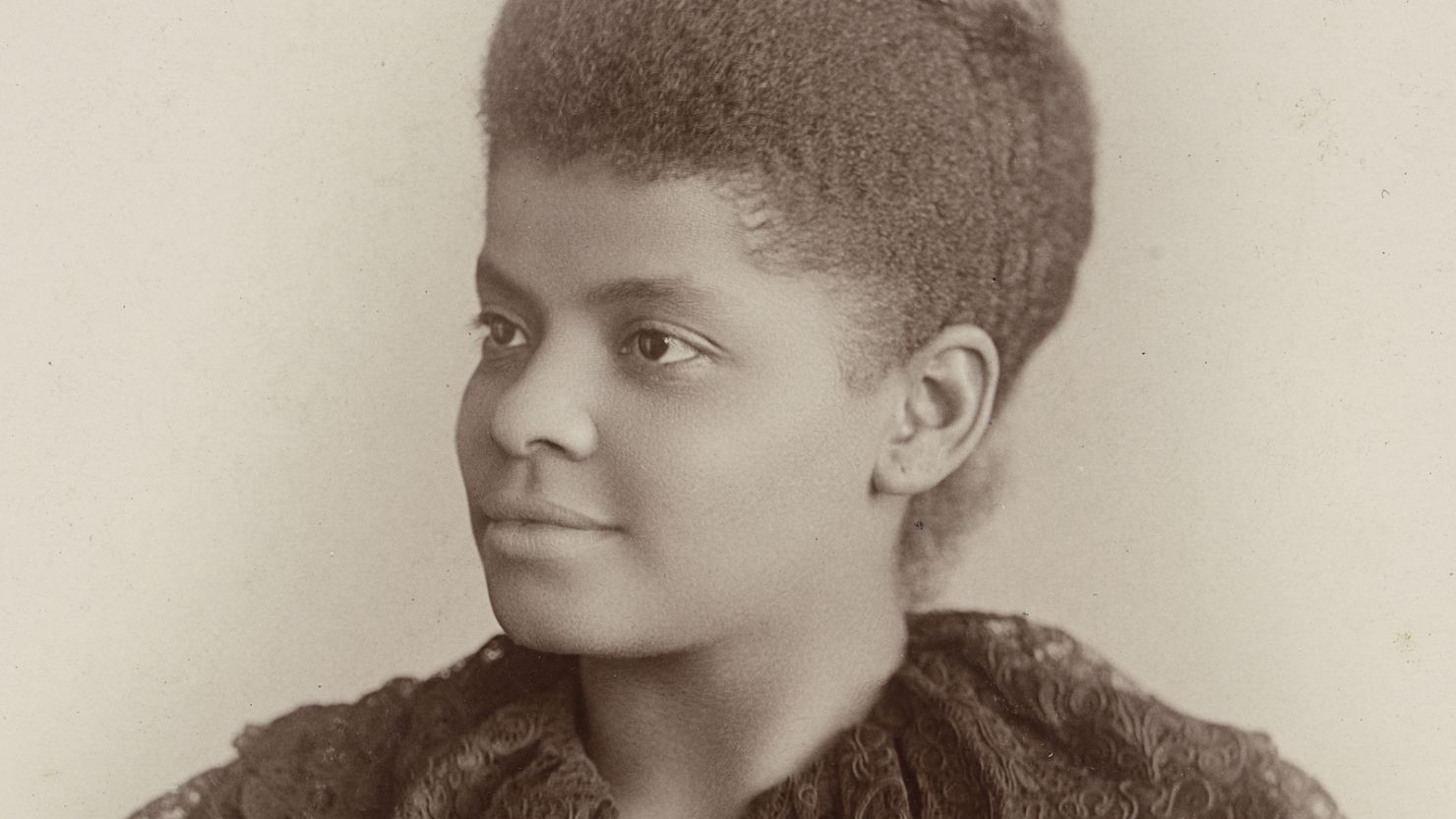

But I did know all about Ida B. Wells, the black woman and activist who was posthumously honored this week with a special Pulitzer Citation. The awards committee accepts submissions from deceased writers as long as the work is not a collection of writings that have been edited after the author’s death. Other posthumous awards have gone to musicians like Hank Williams and composers Thelonious Monk and George Gershwin.

Wells was recognized for her work as one of the nation’s first and most intrepid investigative reporters. Today, she is credited with helping to lay the very foundation for investigative reporting. The Pulitzer citation comes with a bequest of at least $50,000, with recipients to be announced at a later date.

Thanks to the well-worn set of Britannica encyclopedias proudly displayed in our tiny, third-floor apartment, and hours spent in the library reading black history books, I learned about Wells and her career early in my childhood. I loved reading about how this young, fearless black woman, born in 1862, had used the power of the pen to fight against injustice and racism.

Just after the Civil War, Wells launched a crusade against lynchings in the South and published pamphlets-turned books titled: “Southern Horrors” and “The Red Record.” Her books used facts, firsthand information and statistics to record lynchings and details of the murders.

“In slave times the Negro was kept subservient and submissive by the frequency and severity of the scourging, but, with freedom, a new system of intimidation came into vogue; the Negro was not only whipped and scourged; he was killed,” Wells wrote in “The Red Record,” for which Frederick Douglass wrote the introduction.

Her work boldly challenged the pernicious myth that black men were being lynched for raping white women, and she wrote about the murders for what they were: a terror campaign designed to oppress black Americans.

Wells, who was later one of the founders of the NAACP, also co-owned and edited her own newspaper called The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. And it was at her paper, under constant death threats and attacks, that she began to travel the nation investigating and reporting on lynchings. Wells was only 30-years-old at the time. Even after opposition to her reporting made it unsafe for her to return to Memphis, Wells devoted her life to fighting for justice and equality.

And even today, nearly 89 years after her death in 1931, Wells is empowering young black women to continue her fight. Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times was also awarded a Pulitzer Prize this week for her groundbreaking 1619 Project. The brilliant collection of personal essays and investigative reporting examines the impact of slavery 400 years after the first slaves arrived in America.

It is because of Wells, and other freedom fighters like her – Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr. and so many more – black girls like me dared to dream that our words could be used as a weapon against hate and fear. She taught us the power of telling our own stories.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Ida B. Wells gave America a precious gift: A long legacy of women honored to walk in her shadow and continue her work. And it’s satisfying to finally see Wells’ place in history recognized and rewarded. She was a great American who believed in truth and freedom.

And, it’s time for more of the world to know her story.

An earlier version of this op-ed incorrectly listed Bob Dylan’s Pulitzer as being awarded posthumously.