The protesters met up at a gas station.

They taped signs on the sides of their cars and got ready to blare their horns.

Then they drove slowly down the street together.

The scene on a recent evening in Eloy, Arizona, about 60 miles southeast of Phoenix, was different than any demonstration Natally Cruz had joined before.

“I felt chills … just to see how much support there is out there, to see how even at this hard time, people are still trying to find a way to help one another,” says Cruz, who headed to the protest in her black Nissan Maxima with several signs in tow.

One said “honk for justice.”

Unable to gather in large groups because of the coronavirus pandemic, pockets of protesters around the world are turning to a new tactic: trying to make their voices heard from inside vehicles instead of marching in the streets.

One focus of US protests: Immigrant detention

Last Friday in Arizona, organizers say some 200 cars circled outside the Eloy Detention Center and La Palma Correctional Center. For weeks, similar protests have been popping up outside immigrant detention centers across the country.

Advocates such as Cruz are pushing for Immigration and Customs Enforcement to release detainees, who they argue are particularly vulnerable to contracting the virus in crowded facilities that have long faced criticism for how they handle even routine medical care. ICE has said it’s committed to caring for those in its custody and considering releases of some detainees on a case-by-case basis. So far there are at least 77 confirmed cases of Covid-19 among more than 33,000 detainees in ICE custody, according to the agency.

At the Eloy demonstration, protesters showed up with signs that said “free them all” and “humanity over profit.” They honked their horns over and over, hoping detainees inside could hear.

“We want them to know people are out here fighting for them,” Cruz says, “that they’re not being left alone.”

Car protests are popping up elsewhere, too

This isn’t just something that’s just been happening outside immigrant detention centers.

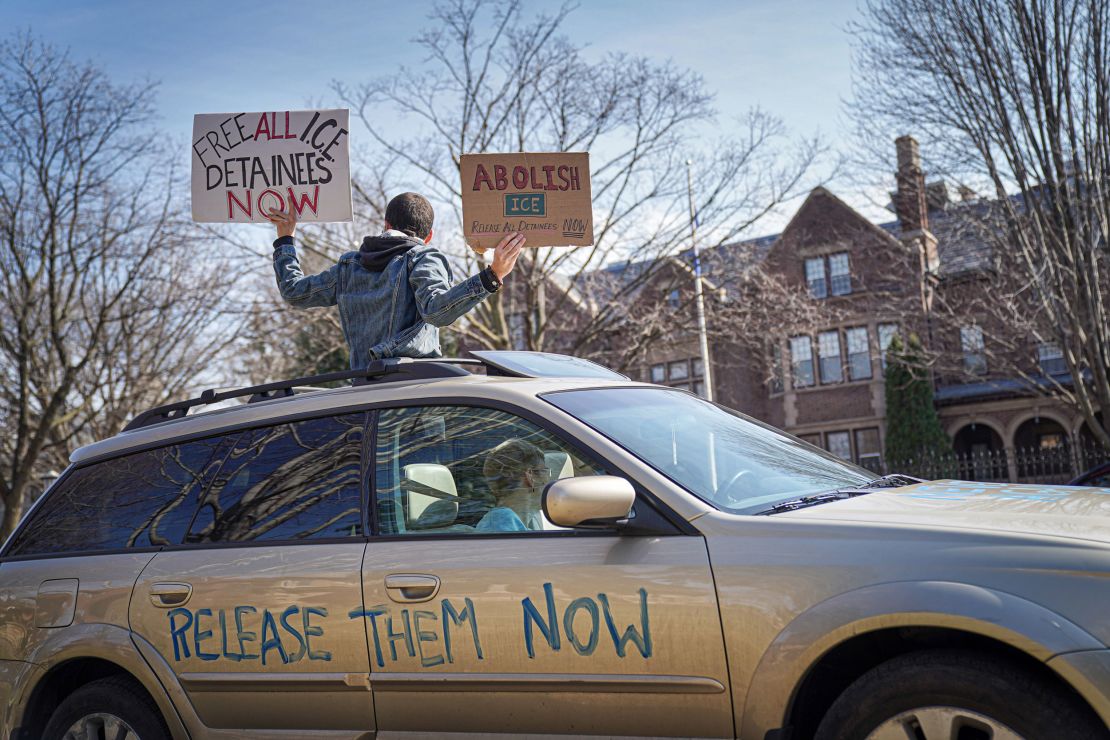

In St. Paul, Minnesota, protesters drove by the governor’s mansion last month as they called for the state to release detainees.

At first glance, images of car protests in some cities – such as recent demonstrations in Philadelphia, Sao Paulo, Brazil and Krakow, Poland – look like they could simply be snapshots of rush-hour traffic.

But flags fluttering across windshield and signs taped in windows show that these aren’t scenes from a typical day on the streets.

This isn’t the first time this has happened

It’s no surprise to see different activist groups turning to similar protest tactics as they struggle to get attention for their causes and find new ways to come together, says David Meyer, a professor of sociology and political science at the University of California at Irvine.

“You’re always looking for something that will work. … You have to be constantly prospecting for stuff,” says Meyer, author of “The Politics of Protest: Social Movements in America.”

And vehicles have been used in protests before, Meyer says. In 1964, for example, a group of protesters from the Congress of Racial Equality organized a “stall-in” to try to keep people from going to the World’s Fair in New York – though in the end far fewer protesters showed up than organizers had originally promised. And in 1979, he says, farmers demanding more pay for crops headed to Washington in their tractors. Participants in the so-called “tractorcade” occupied the National Mall for weeks.

Now activists trying to make a point have more tools at their disposal. As the coronavirus pandemic spreads and government orders keep many at home, activists have been working on building capacity and attention for their causes online, Meyer says. But there are limits to internet organizing.

“Mostly that ends up talking to the people who already agree with you and already are with you,” he says. “The car protest is one way to try to break through those boundaries.”

But there could be pitfalls to protests inside vehicles, Meyer says. It’s harder to connect with fellow protesters from inside a car, he says, and vehicles may be viewed as more threatening.

“When protesters wear helmets or gas masks, it almost always leads to police feeling threatened and reacting more harshly. Do cars do that, too? I don’t know,” Meyer says.

More car protests are planned

Immigrant rights advocates have said they’re planning additional car protests. And other groups are, too.

Conservative critics of Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer have said they’re planning to surround the state’s capitol Wednesday – not only with cars, but also with construction vehicles, landscaping trucks and trailer boats representing industries that have been impacted by the governor’s stay-at-home orders.

Protesters argue that Whitmer has gone too far.

“She’s driving us out of business. We’re driving to Lansing,” says a Facebook invitation for the event, which is dubbed “Operation Gridlock” and organized by the Michigan Conservative Coalition.

Whitmer has pledged to reopen the state as soon as it’s safe and is asking for patience.

Monday she called for people participating in the protest to remain in their vehicles “so that they don’t expose themselves or any of our first responders to potential Covid-19.”

“I support people’s right to demonstrate,” she told reporters, “and to use their voice.”