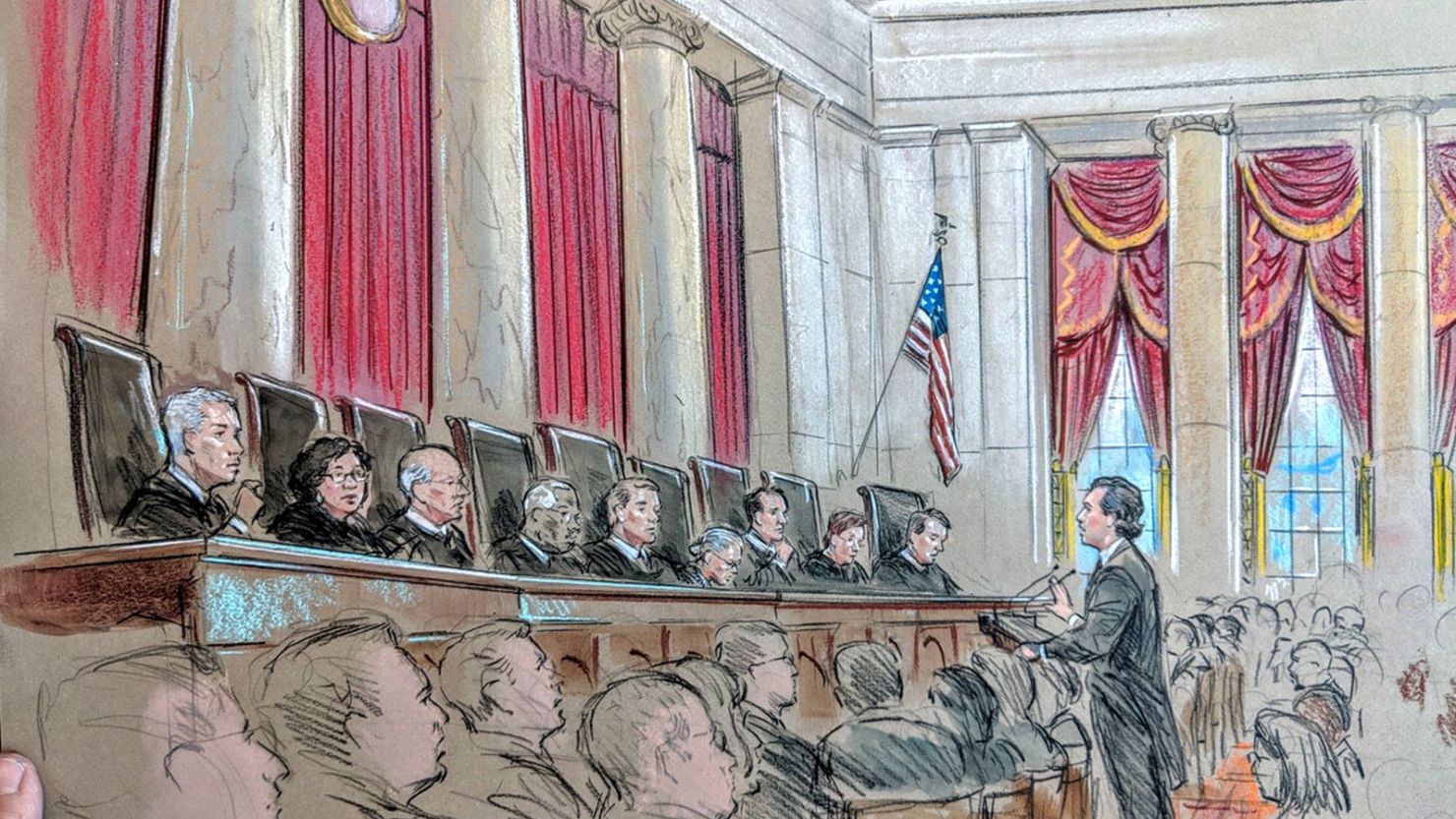

The Supreme Court’s announcement on Monday that it would livestream oral arguments in 10 cases next month, including three centered on President Donald Trump’s financial records, is a historic breakthrough in public access to America’s highest court.

The decision to make their teleconference arguments public brings some immediate transparency to an insular institution that has long prided itself on resisting technology and live broadcasts of any kind.

It is, to be certain, a limited move. There will be no video pictures of the black-robed nine as they question lawyers in cases, and the court is allowing access to real-time arguments only for special May sittings during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The courtroom is a very special place,” Chief Justice John Roberts has asserted. “Maybe part of what makes it special is that you don’t see it on television.”

Oral arguments in Bush v. Gore, which decided the 2000 presidential election, were not broadcast live. Neither were oral arguments over the fate of the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as “Obamacare,” same-sex marriage or abortion rights controversies. Only those who waited in line for a seat in the courtroom could attend and follow in real time. For some cases, the justices made an audio recording available later in the day.

The usual practice has been for the court to put an audio link on its website each Friday, useful for the historical record and legal followers, but not necessarily an exciting draw for the general public. Only for a few high-profile cases have the justices even released audio recordings on the same day as an argument.

Now, even the President, if he chooses, can tweet along with the action.

The announcement demonstrates, after a month of postponing any action on disputes scheduled for March and April, that the justices are willing to change their ways – as a multitude of lower court judges already have – to get their business done.

Scholars and students of the court lauded Monday’s announcement, even as they questioned whether it would truly modernize.

“This is good for public education. It’s good for the court coming into the 21st century,” said Barbara Perry, a longtime Supreme Court expert at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

Perry wondered whether the justices might be against regular livestreaming when the country returns to regular ways.

“Could it be the tip of the camel’s nose under the red velvet curtains? … I’d say probably not,” Perry said, adding that televised hearings are unlikely to come in the near future.

Among the controversies to be heard in May are two Trump challenges to US House subpoenas for financial documents from his longtime accounting and banking firms. That pair and a third case that will be heard, arising from a New York grand jury’s investigation tied to Trump tax records, had been scheduled for March 31.

Lee Arbetman, executive director of Street Law, which helps high school teachers develop materials about the court, said airing the Trump-US House document dispute would enhance civic awareness.

“There’s a potential for a greater understanding of democracy, on the checks and balances of government,” he said. “But does one oral argument an educated citizen make?”

For lawyers, justices, and the public, the hour-long public sessions are an important but not crucial part of the decision-making process. Lawyers put their most comprehensive arguments in written briefs. But the oral arguments allow lawyers to address tough questions about their cases and give the justices themselves an opportunity to telegraph their views and begin persuading each other.

The justices have often expressed concerns that listeners would get the wrong impression from arguments, for example, if they play “devil’s advocate” in their questions or focus on a relatively minor issue for clarity. Some justices try not to tip their hand or, perhaps, are truly uncertain about which side they favor before the case is put to a vote in their private meetings.

Still, the sessions are invaluable to the public. The arguments provide the only opportunity to see all the justices wrestling with the case, in the open, and to witness their personal predilections and interactions. Spectators visit the courtroom, especially, to see a newly appointed justice, such as Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, or to watch an enduring icon, such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg, “The Notorious RBG.”

Arbetman and other educators said the value of Monday’s development would rest in livestreaming becoming the rule rather than the exception and in eventual televising.

Until Monday, some 20 cases were in a suspended state, delayed but with no signal from the justices of whether they would resolve them before the court’s usual end-of-June recess. The justices said they will hear a designated 10 cases in the first two weeks of May and the rest of the cases in early fall. It is not known whether that latter group, which could be aired in the courtroom, would be livestreamed.

An institution that’s always been the exception

Many state courts already televise their proceedings, and plenty of state and lower US courts have already opened up teleconferences to the public during the pandemic.

On Saturday, the Kansas Supreme Court allowed the public to watch a Zoom argument session of judges questioning lawyers in a controversy over the governor’s ban on public gatherings, including for religious observances. (The court upheld the governor’s order.)

The justices’ initial moves to handle the pandemic were ambiguous. They issued orders regarding the allotment of argument time between parties but left open when those cases would actually be heard. Until Monday, lawyers, who continued to prepare filings and cautiously try to be ready for arguments, had not received any formal word about alternative methods for airing the March and April disputes.

For some of the pending March and April cases, there appeared more urgency. One dispute, relevant to the upcoming presidential election, tests whether states may fine or remove Electoral College delegates who refuse to cast their ballots for candidates to whom they were pledged. That will be heard in May.

And lawyers for the US House have been seeking clarity on their power to compel information from the President and scrutinize the White House. Lower court judges upheld the House subpoenas issued to Trump’s accountants and banks. But the high court in December had accepted the Trump appeal of the disputes.

The earlier high court postponement increased the likelihood that Trump would not be forced to turn over personal business documents before the November election and cast doubt on the investigative authority of the House of Representatives.

Among the cases heard in earlier arguments during this 2019-2020 term and still awaiting resolution involve whether federal law protects LGBTQ workers from discrimination, whether Louisiana abortion regulations infringe a woman’s constitutional right to end a pregnancy, and whether the Trump administration’s plan to deport certain undocumented immigrants who came to the US as children can proceed.

Now it appears that those earlier cases and the new select slate, including the Trump controversies, would be decided by summer.

Stay tuned.