American farmers are concerned.

The coronavirus pandemic is posing a threat to their livelihoods, as it is for many others across the globe. But unlike some shelf-stable goods producers, farmers have very little flexibility. They’re on a strict planting and harvesting schedule and cannot ramp up or decrease production at will.

“A peach [that] is good today is not good tomorrow. That’s how quick things ripen,” Chalmers Carr told CNN Business. Carr owns and operates Titan Farms in Ridge Spring, South Carolina, where he grows peaches on around 6,200 acres, in addition to bell peppers and broccoli.

For blueberries and strawberries, he said, “if you leave them on the bush or the vine one extra day, they’re virtually worthless.” Even more forgiving crops, like bell peppers, have a short harvesting window of two to five days, Carr said.

April and May are critical planting and harvesting times for many US farmers. They need skilled laborers to work their fields, and a reliable supply chain to deliver their goods. And they don’t have any time to waste.

If farmers can’t find enough workers or if their farming practices are disrupted because of the pandemic, Americans could have less or pricier food this summer. And because international farmers and their supply chains face similar problems, we could receive fewer food imports, potentially limiting supply and driving up prices.

In recent weeks, many Americans got a scare when they walked into grocery stores and found empty shelves. Those shortages are caused by bottlenecks in the supply chain, not a lack of food, so grocery stores have been able to replenish their shelves fairly quickly.

What happens over the next several months will determine whether those disruptions become more serious.

Farmers are scrambling to solve problems as they arise, and it’s unlikely that we’ll run out of food. But this year and next, we may not see the bounty we’re accustomed to.

A foreign workforce

As efforts to contain the coronavirus pandemic limit consular services, US farmers are worried they won’t be able to hire the international workers they rely on.

“We are a sector that is very dependent upon guest workers coming into this country, particularly for the planting and harvesting of specialty crops [like] fresh fruits and vegetables,” said Chuck Conner, president and CEO of the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives.

According to the USDA, in fiscal year 2005 the government distributed 48,000 H-2A visas, which grant foreign workers temporary access to the country as agricultural workers. In fiscal year 2018, that figure had quintupled to about 243,000. Because the average length of the visa stay was about five months, the agency estimates that those visas were the equivalent of 108,000 full-year positions.

The spike in the number of visa holders is “one of the clearest indicators of the scarcity of farm labor,” said the USDA.

The 2015-2016 National Agricultural Workers Survey, the most recent of its kind, found that 69% of hired farm workers interviewed for the survey were born in Mexico. Only 24% were born in the United States.

H-2A workers have been deemed essential by the government, and should be allowed to work in the United States. These workers don’t seem to be avoiding coming to the United States for fear of catching Covid-19 — the economic incentive is just too large to give up, Carr said. But workers may eventually decide it’s too risky to enter the United States.

And if they do have a hard time getting in, it’s not clear that domestic labor will be able to fill in the gap.

Labor mismatch

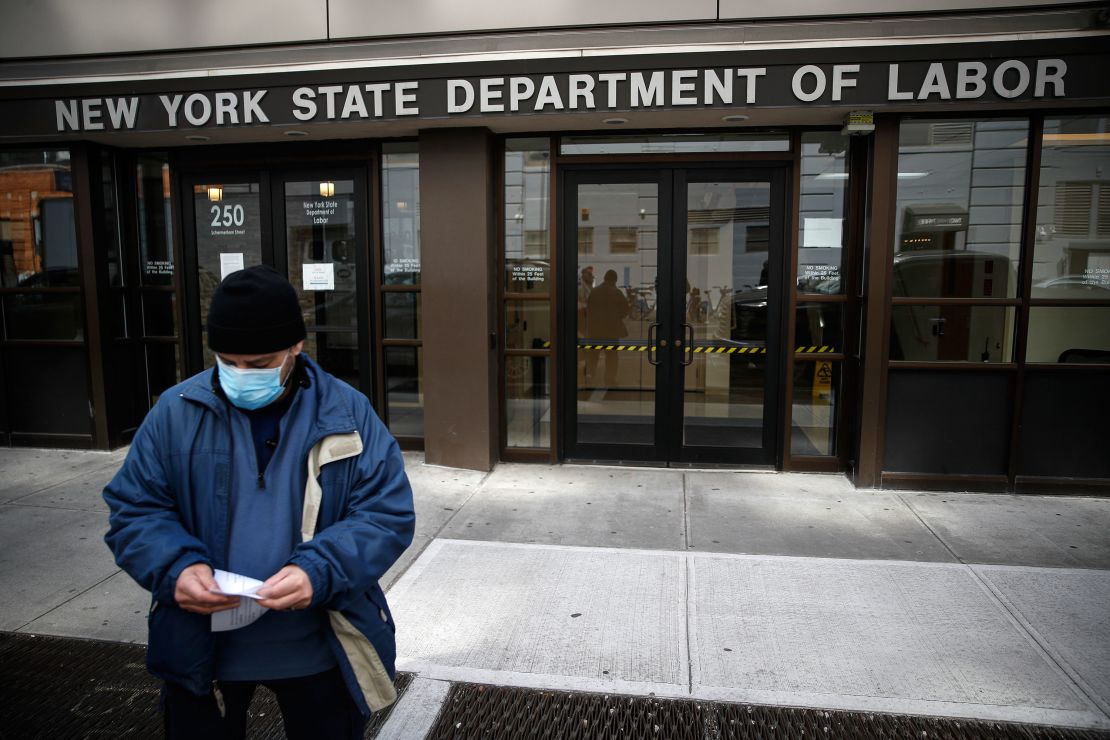

It might seem like there’s an obvious solution to the problem. US unemployment claims have reached unprecedented levels as businesses close their doors because of the pandemic. In the week ending March 21, initial jobless claims reached a seasonally adjusted 3.28 million — the largest number since the Department of Labor started keeping track of the claims in 1967.

People currently seeking work could find it on farms. But most of the newly unemployed are not qualified.

“It’s very skilled labor,” said Tom Stenzel, president and CEO of the United Fresh Produce Association. “If you’re a peach picker, you’re very different than a strawberry picker. And the ability to handle the volume and keep up with the pace — it’s a professional job.”

People without experience could theoretically transition to agricultural work, he said. “Farmers will hire anybody that they could right now, I would bet you.” But they wouldn’t be very efficient, and could slow down farm operations, he added.

And it’s unlikely that unemployed Americans will actually seek agricultural jobs, or relocate to take that type of work. Carr said that in general, he’s found it very difficult to recruit American workers. “There was no domestic workforce for me,” he said.

“It’s tough work, out bending over, harvesting crops all day,” Stenzel said. “It’s very hard to get Americans to do that.”

Red tape

The government has been racing to adapt its ordinary procedures to this extraordinary situation, but it’s not clear that its efforts will be enough.

Adjustments and tweaks to visa processing and other protocols have been made as problems arise. In light of concerns that workers won’t be allowed into the country because they can’t have in-person interviews, the State Department is allowing consular officers to waive those interviews for some. But it’s hard to predict the bumps in the road, especially because government efforts to prevent the spread of the virus have been changing dramatically over short periods of time.

Those ad-hoc measures may be enough for now, said Carr. But if the pandemic stops domestic agricultural workers from doing their jobs over the next two or three months, US farmers will need a new influx of international employees. The current adjustments don’t offer a road map for that possibility.

Plus, farm laborers face the same threats that other essential employees do. While many Americans are instructed to stay home, they’re expected to go out to work every day. They may get sick, and be quarantined or unable to work. Or they may have to work less to take care of children or relatives. Social distancing practices may disrupt how they function, and introduce friction into their normal farming processes.

That goes for other critical employees across the supply chain, like truck drivers. It also applies to farmers in other countries: They too could get sick, quarantined, or have to stay at home to care for loved ones, and they have their own supply chain disruptions to consider.

International disruptions

Much of the fresh fruits and vegetables that are consumed in the United States are grown internationally. The FDA said last year that about 32% of fresh vegetables and 55% of fresh fruit consumed in the United States each year are imported.

That doesn’t mean that half of apples, or a third of potatoes, come from abroad. Certain fruit, like bananas, are grown almost entirely outside of the United States. And imports tend to increase or decrease depending on the time of year — you can buy fruit out of season because they’ve been grown elsewhere.

If those other countries aren’t able to produce as much as usual, Americans could see fewer fruits or vegetables out of season. And the ones that get here may be more expensive.

“Supply shortfalls would drive prices up, and yes, you’d get less,” said Andrew Muhammad, a professor of agricultural, food, and natural resource policy at the University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture.

Even if international farms are not interrupted, imports may be held up because of staffing shortages at shipping ports, he said. And if ships are stalled at docks because of decreased labor, or if storage facilities aren’t emptied out to make space for new products, Muhammad added, those countries’ export markets could suffer.

Still, that doesn’t necessarily mean international markets won’t be able to meet US demand. But it does mean that producers, here and abroad, will have a hard time planning for the future.

Uncertainty ahead

Growers are “planting right now for late spring, summer,” said Ed O’Malley, vice president of supply and merchandising at Imperfect Foods, a discount grocery delivery service that sells so-called ugly produce to help prevent food waste. “They’ve gotta be wondering, ‘how many acres of lettuce or green beans do I plant?’”

Before the pandemic, demand in food service was “very predictable,” he added. But now, with restaurants closing their doors and grocery stores seeing surges in purchases, it’ll be harder for farmers to know how much they’ll be able to sell and to whom.

“For a grower to go ahead and plant 2,000 acres when he’s really only going to need 1,200, boy, that’s a very expensive proposition,” O’Malley said.

The inability to plan could exacerbate the country’s food waste problem, and make it harder for the food insecure to eat.

It will take grocery stores some time to readjust to changes in demand. Prices for some staples, such as eggs, have surged as demand far outstrips supply. And some US food banks “reported a sharp decrease from food retail donors due to the stockpiling that has occurred throughout the country,” Blake Thompson, chief supply chain officer at Feeding America, a national network of about 200 food banks and 60,000 food pantries and meal programs, told CNN Business in an email.

But some food has been diverted successfully from one venue to another. Baldor, in New York City, generally sells food to restaurants, schools and other food service outlets. Now, it is offering delivery to individuals. Imperfect Foods was able to accdept food meant for airlines, said company co-founder Ben Chesler. “We’ve seen lots of offers come in [from] companies that have been made for food service.”

Between the disruptions, uncertainty and shocks to the global supply chain, the situation is unstable but not hopeless, experts say.

“You can’t throw too much of a worse scenario at producers than what they currently have,” said Conner of the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives.

“Our system has responded well. And I think that’s going to continue,” he added. “I know that’s a bold prediction because the world is being turned upside down here, and I recognize that. But I have great confidence in this system’s ability to respond and get food to the people where they need it.”