Editor’s Note: Jennifer S. Hirsch is professor of sociomedical sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. She is the co-author, with Shamus Khan, of “Sexual Citizens: A Landmark Study of Sex, Power, and Assault on Campus,” from WW Norton. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

Arizona’s schools are closed, but only through March 27. Maine has “recommended” that schools move to online instruction. California’s schools, however, will likely not reopen this academic year.

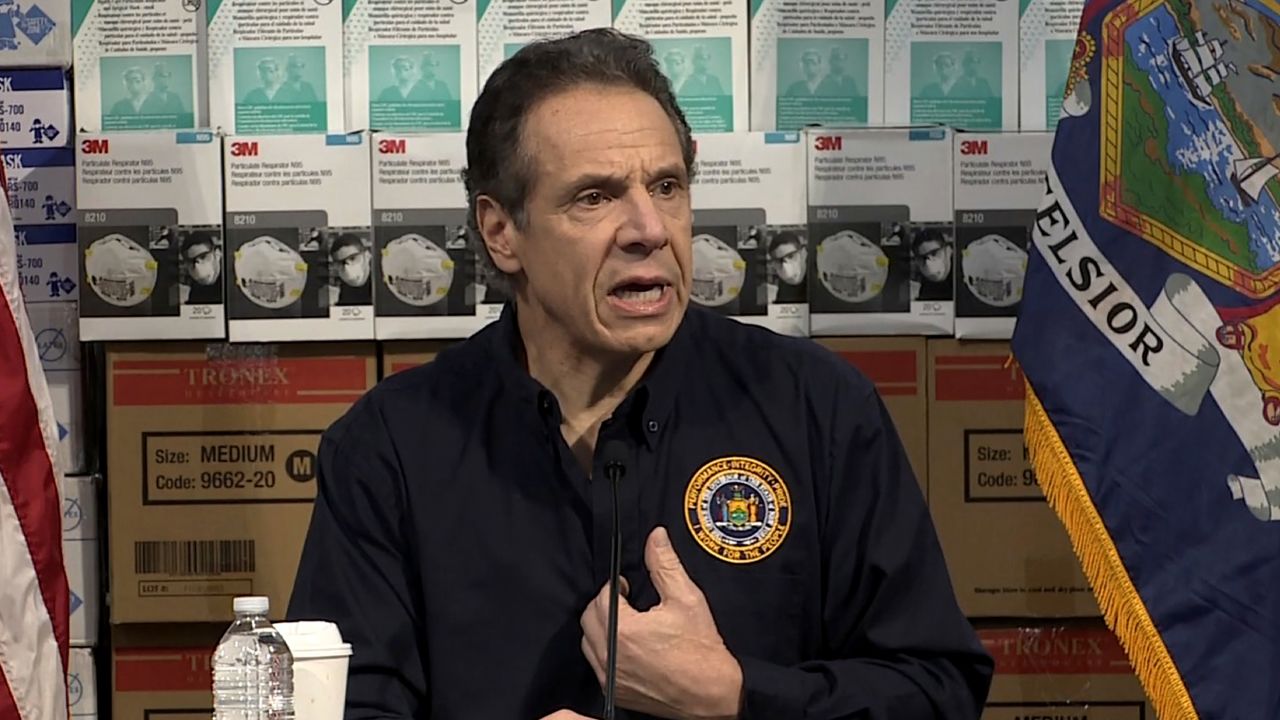

It’s not as if the governors and state directors of public health have access to different information about America’s coronavirus crisis. There’s a lot of love for governors in the public conversation right now. But while some of them are taking decisive action to reduce overall mortality, others seem more focused on propping up the Dow. The muscular mandates on social distancing from both Republican Mike DeWine of Ohio and Democrat Gavin Newsom of California underline that this does not need to be a partisan issue.

In counting the heroes and zeroes of the pandemic, our deepest scorn should be for those governors, mayors and other officials who have been slow to take state action. They seem not to grasp the urgency of sacrifice for our shared well-being. Some business organizations have been similarly selfish; the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, for example, wrote to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on March 20, asking her to avoid issuing a “shelter-in-place” order for the state because the brunt of the problem is – at the moment – concentrated elsewhere.

A set of projections done by colleagues of mine at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health show how three different scenarios – “no control, some control, severe control” – play out in terms of the progression of coronavirus across the country.

With no control, people can try to do their part to flatten the curve, but schools, entertainment and houses of worship remain open, and business proceeds as usual. “Some control” entails “partial adherence to social distancing guidelines and a patchwork of government-imposed restrictions on work, travel, and dining out.”

The severe control scenario describes daily life in New York at the moment: Only work deemed essential is done in person, everyone who can do so works remotely and all institutions that create large gatherings – schools, entertainment, restaurants, sports leagues – have had those activities suspended.

These projections make abundantly clear that many more people will get sicker sooner under the “some control” scenario than under the severe scenario. And it’s important to note that the “some control” scenario doesn’t describe an average spread uniformly across the nation. Rather, it’s variable, at both policy and individual levels. “Government-imposed restrictions” reflect political leadership; individual “adherence to social distancing” is the part that’s on each of us.

Yes, the level of suffering caused by those changes and restrictions is high here in New York, even among those who are healthy. Knowing that so many of my fellow New Yorkers suddenly face life-and-death shortages of personal protective equipment in hospitals, while others face less life-threatening, but also dire job loss and business loss, provides some perspective on the worry about my husband’s canceled surgery to remove a basal cell carcinoma, the disappointment I feel about a suspended book tour or my sadness about the lost milestones for both of our children.

A friend whose mother died last week had no funeral or shiva to cushion the loss. And that is just one of the tiny grief bombs that have exploded across the country as part of the epidemic’s social ripple effects. But we understand that we are doing our part for the common good.

In any American public health crisis, you can reliably predict that both politicians and the general public will emphasize changing individual behavior. And in relation to social distancing, individual behavior has been highly variable. Last week, a story about spring breakers partying on – despite warnings not to do so – quoted one partyer who said, “If we get sick, we get sick. We’re not going to die.” Said her friend, “We might as well stay and get hammered.”

When the history of this moment is written, it seems safe to say that we will reflect on words like those as showing an astonishing and consequential lack of understanding of how, as we face a global pandemic, our futures are bound up together.

If there ever was a time for the nanny state, this is it.

There is no clearer example of the harm caused by free riders than infectious diseases. While the planes are flying, the highways are open and the trains are running, they put us all at risk.

The projections make it clear that – except for those in a few counties in Oregon and Montana – by the end of August even the states with very few cases now will see a future where everywhere has infections, according to Columbia University’s projections.

Mortality projections range substantially – from the widely-cited Imperial College of London chilling prediction of 2.2 million deaths, to former CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden’s still-awful projection of more than 1 million, to a set of CDC scenarios that were first reported by The New York Times that ranged from 200,000 to 1.7 million dead.

Beyond the noise in the numbers, however, there is clear agreement: Whatever the worst-case scenario is, acting together can help avert it.

Early last week, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt’s office was still telling residents to “to remain calm, live your life and support local businesses.” By mid-afternoon Tuesday, he had changed his tune, saying, “We need all Oklahomans to take this really, really seriously,” in the wake of ballooning Covid-19 cases. As of Tuesday, Oklahoma’s governor instituted a shelter-in-place order – but only for individuals older than 65 and those with underlying health conditions.

The “living your life” attitude fails to acknowledge that doing so may cost someone else theirs. The problem isn’t just with the governor of Oklahoma taking his own family out for dinner; it’s his slowness, and that of all the other laggard governors, to create conditions in which those dinners out are not individual choices.

As a nation, we face a limited supply of hospital beds, masks and ventilators – not to mention doctors and nurses. Every state and local politician who is focused on local economic conditions rather than our shared epidemiological future is being a public health free rider, prioritizing a delusional view of what will make them electable over solidarity, while shifting the burden of flattening the curve to, at the time of writing, the 200 million Americans in 21 states, 47 counties and 14 cities enduring shelter-in-place orders.

Those decisions rest largely in the hands of governors, mayors and county executives. No city is an island – not even Manhattan, which is an actual island.

Thus, the moment in which we find ourselves: Those of us in states with robust responses are still vulnerable, no matter how much sacrifice we make for the greater good, because of states with weak responses.

Get our free weekly newsletter

This moment offers no shortage of heroism, and also an unending parade of individual bad behavior; the hand sanitizer hoarder was quickly replaced by stock-selling senators, and tomorrow a new self-dealing scandal beckons.

Certainly, we can continue to look with disdain at those who are scoffing at recommendations for social distancing, as they put their own desire to party ahead of our collective well-being. But those who will unquestionably have failed us all are the governors and mayors who put the economic well-being of their own states and districts ahead of our collective health as a nation.